Chen Peiper, born in the Netherlands, is an esteemed Israeli jewelry designer and teacher, and over the last two decades has been a glass sculptor. As an artist, she is very sensitive to and perceptive of the surrounding realities.

In her career, Peiper’s works have been on show at numerous solo and group exhibitions in Israel (in 2023 at the Tel Aviv Bienniale of Crafts and Design at the Eretz Israel Museum), The United States, and Europe.

She works with different techniques, using materials such as gold, silver, stainless steel, aluminum, and copper. When designing sculptures, she combines glass with metal.

Her works reflect her personal experience (as in her solo show “Fish Plus” in 2020) and social exposure.

In 2022, Peiper participated in the Venice Art Bienniale, presenting Covitrum – 18 glass anonymous faces in various masks worn during the pandemic. There, she also showed the powerful Refugees, dedicating it to the African emigrants.

The artist’s latest work, New Life, is centered on the motif of Israeli flags, which expresses Peiper’s deep concern for the situation in Israel, during last year’s protests and the ongoing war.

In an interview with the Magazine, Peiper said that she made aliyah during the Yom Kippur War, and she shared her memories from that crucial-for-Israel time. This was in 1973, when Peiper was nearly 27 years old, and the State of Israel was only 25. Almost as peers, they grew up together.

Before we move on to your current work, as a sea lover I must ask you about your solo exhibition from 2020 about the underwater world, ‘Fish Plus.’ Why fish?

It’s related to my childhood in Holland. My parents used to have a summer house by the sea, and I was always on the water: in a sailboat, a rowboat; I was very sporty, and the water was very important to me. I was living in it. So I made sculptures of what I remembered.

But also one of the sculptures was inspired by a drawing of my grandson, which he made when he was six years old. All the sculptures were in the fusing technique; I used transparent and hand-painted glass, combined with silver, copper, and iron.

A magical experience for the viewers and a nostalgic trip into your past. Speaking of your past, when we first met, in December, you said that you moved to Israel 50 years ago…

Yes, in 1973, in the middle of the [Yom Kippur] War. I made aliyah at the age of 26, almost 27. I was already after my jewelry design studies at Rietveld Academy of Art, in Amsterdam. I had been already working. We (my husband and our one-year-old daughter, Tamar) were already on our way to Israel when the war started.

Were you on the plane?

No, my husband said that the plane went too quickly, and he wanted us to have an adventure, so we went on a cruise, on a ship to Israel. We started it from the south of France. Just as we were about to begin our trip, some people told us there was a war in Israel. Then, we wanted to make aliyah even faster.

The war didn’t stop you from this move?

No, when you want to live in a country, a war is not a reason to go away. You stay here; you don’t leave the country because of a war.

And why did you want to make aliyah in the first place?

My husband is Israeli, born in Tel Aviv. He has lived in Holland for 10 years, and we met at the Academy of Art. We could have stayed in Holland, but it was clear to us that we could not live in both countries, and we decided that we wanted to live in Israel.

Following this decision, you arrived in the middle of the Yom Kippur War...

It happened like that. We moved in with Gidi’s, my husband’s, parents in Ramat Hasharon, which made things much easier.

How was Israel back then? How do you remember Israel during the Yom Kippur War?

Cities without men. Tel Aviv, Hod Hasharon, completely without men. For a few months, it was like that. Life was quieter. There was nobody on the streets. It was a real war for us in the center of Israel. Now during the war people continue their lives, shops are open, and people are sitting at coffee shops; back then, the streets were empty. But also the streets looked different. Now everything is modern; in 1973 there were clouds of sand on the roads of Ramat Hasharon.

And how different was the society of Israel back then in comparison to today’s?

It’s hard for me to say. I jumped into the group of Gidi’s friends. They all were in the army and all talked about the army, so it was difficult. And they were shy to speak in English to me at that time.

But in general, you could have visited a friend or a neighbor anytime. Now you must call or text to set up a visit. [Back then,] the doors to the apartments were always open.

From what you are saying, it sounds like people were closer to each other. As we speak, I’ve just realized that you and the State of Israel are almost the same age. Since 1973, the very young state of 25 years and you, almost 27 years old, as peers you grew up together.

I have never thought of this, but this is true, yes. [She laughs.]

And after the Yom Kippur War, how do you recall Israel?

We all worked very hard. We wanted to build something, and we felt we did.

Do you mean your life or also Israel?

Also Israel.

So after the war, you started to work in your profession, as a jewelry designer?

Yes, at home. People have come especially to me. I looked at how a person behaved and what he [or she] liked, and based on that I was designing.

Before shifting to glass sculptures (which is your main focus right now), for 40 years you were creating jewelry, showing it at professional exhibitions in the Netherlands, Israel, and the US, and you were also teaching how to design.

Yes, I taught design at a technology center for jewelry in Tel Aviv (1985-1995), and in 1993 at a special program for Bedouin girls and young women who were making traditional Bedouin jewelry but wanted to learn about other approaches; and (in the years 1990-2000) at Beit Berl art college in Ramat Hasharon, where I was head of the jewelry department.

So you had an established professional position, and suddenly in 2002 you went to Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design to study glass design. What triggered that?

I was looking, for a long time, for something else. I hoped that if I had another material, it would be more interesting for me and more creative.

My husband, who has been always very supportive of me, saw in a newspaper that there was an opening of a new department of glass, as a second degree, at Bezalel. I applied and got accepted.

It was two years of hard work, but it was very interesting to me to learn various techniques of working with glass. It was wonderful, in the middle of my life to start with a new material! But I have never forgotten about my metal. The metal always helps me to design the inside of the glass. It adds the feeling. I have combined it with glass.

What attracts you to glass?

It can be transparent and doesn’t have to. You can do everything with it, move it in all the directions you want to. Another thing, jewelry is also art, but when you create in gold it is [displayed] in a glass box; people can’t touch it. And I like it when people can touch a sculpture.

It changes the experience of the viewers. With your art you reflect on your personal experience, but also on group and social exposure, such as war, the issue of African refugees, or the pandemic. In 2022, at the Venice Art Bienniale, you showed [the installation] Covitrum (COVID and vitro, ‘glass’ in Latin), a series of glass sculptures – unrecognizable portraits, without distinction in gender or skin color. These faces were covered with different masks worn during the pandemic.

Yes, the only distinction was that I made 13 adults and five children (representing my five grandchildren), together 18. I chose this number because of its gematria; the number 18 means chai – ‘life,’ in Hebrew.

Why did you want to incorporate a number important in Judaism, in a way taking away from the universality of this project?

It was very important to me because it is a very powerful number. Each head was covered with a different mask. In these masks I put the story. A mask is a tool of pretense and protection, and it allows introspection. It gives a space to reveal or hide the identity and feelings. One of them was transparent, and I called it ‘Read my lips.’ But there was also the Israeli flag, the Venice flag, and a rainbow LGBTQ flag mask.

On view in Italy, there was also your sculpture Refugees, dedicated to people who fled their countries across the sea in inhuman conditions. A huge unresolved issue of African emigrants often losing their lives on the way to Europe was expressed in your powerful sculpture.

I wanted to show the colors of the sky and the sea and, in between, human beings. The sea was their last refuge. They were mostly Black people, so I used the colors black and red (as blood). You can see that they are all on the boat, but one is outside – didn’t make it.

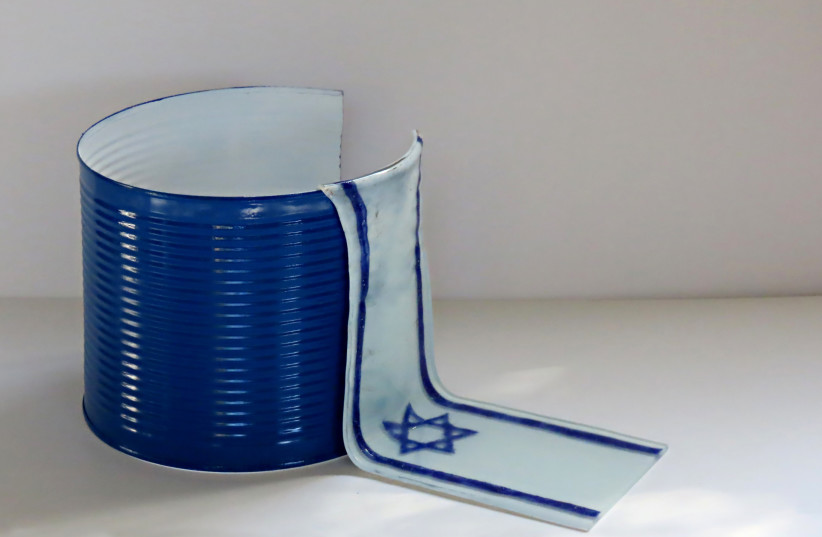

You responded to this tragic reality with extreme sensitivity. Your latest sculptures are also very socially engaged. In December 2023, at a group exhibition ‘The Colors of Camouflage,’ at the Periscope Gallery in Tel Aviv, you presented two series of work: ‘Upside Down,’ in camouflage military colors, and ‘New Life,’ with motifs of Israeli flags in glass, flowing in different shapes. In both cases, you’ve connected a very smooth and elegant movement of glass attached to very simple and basic metal food cans. What was the idea behind this concept? And did you make this series of sculptures before the war or during the current war?

I started before the war. During the war, my feelings about it were even stronger. I am very connected to my grandsons, what they do.

Do they serve in the army now?

Yes, three of them. I am very proud of them.

So the colors came from your grandsons?

Yes, although not directly. I was worried, in general. The flags, at first, were connected to the last year’s demonstrations in Israel. I wanted to show the sadness of thousands of people being with a flag during the protests. I was concerned about what would be with this country and what was going on. I am still, I am worried.

What do think will be with Israel?

The future will not be easy. But I think that we are very strong, and we have to be very strong.

We are talking after many months of war, and you are wearing a ‘Bring Them Home’ necklace [in solidarity with the hostages], and you are still saying that we are very strong?

This is a very scary and ugly fairy tale. But, of course, we are very strong! Otherwise, we – you and me – would not be here today.

So how do you see the future of Israel now, also with the new wave of antisemitism around the world?

When I listen to my daughters, Tamar and Dafna, they are worried. When I listen to my grandsons, they are full of life and they believe that everything will be fine.

Why did you connect flags with simple cans?

They are real cans, reused. By adding a flag to them, there is something new, and maybe there will be something new in the region, not the same as it was before.

Whatever happens in Israel, I express it in my art, both my jewelry and glass sculptures. But the first reason why I used the cans was practical – the metal [material] and its form. Then I realized that I could use different shapes of cans, which gave me new feelings.

When I saw these sculptures at the exhibition, looking at the Israeli flags made of glass, I thought that this was Zionist art. Is it okay to call your art Zionist?

I am very pleased to hear it!

Do you think there is a place for something like Zionist art, that the Israeli artists will want to go in this direction?

This is interesting, what you are asking. When I look back at the exhibition (and this is very important, to look back and check with yourself what you did), I ask myself if it was only the obsession of flags. But it wasn’t. In every piece, I put my feelings inside.

How would you name these feelings?

New life.■

On April 18 at 7 p.m., at Beit Yad LaBanim cultural center, 2 Hamahteret Street, Ramat Hasharon, a group show will open which will include one of Peiper’s new works, View of Israel.

The artist’s website: chenpeiper2.wixsite.com/chen