Everything about the movie June Zero, which opened in theaters throughout Israel on May 2, is unusual.

This includes the fact that the director and co-writer of this quintessentially Israel movie, which tells several stories connected to the building of the oven that was used to cremate Adolf Eichmann after his execution in 1962, is an American: Jake Paltrow, and yes, he’s Gwyneth’s brother.

Paltrow has made several previous films, including the excellent 2007 The Good Night, about a man who wants to achieve in his dreams what he couldn’t accomplish while awake, starring Gwyneth Paltrow, Penelope Cruz, Danny DeVito, and Martin Freeman.

Paltrow, whose late father, the director, Bruce Paltrow, was Jewish, became interested in the stories surrounding the Eichmann trial, especially concerning the fate of Eichmann’s body, and began researching them in detail. Deciding that for the sake of authenticity, any movie about this topic would have to be in Hebrew and needed a screenwriter who was an Israeli native, he brought on director Tom Shoval, who made the movies Youth and Shake Your Cares Away, to collaborate with him on the screenplay.

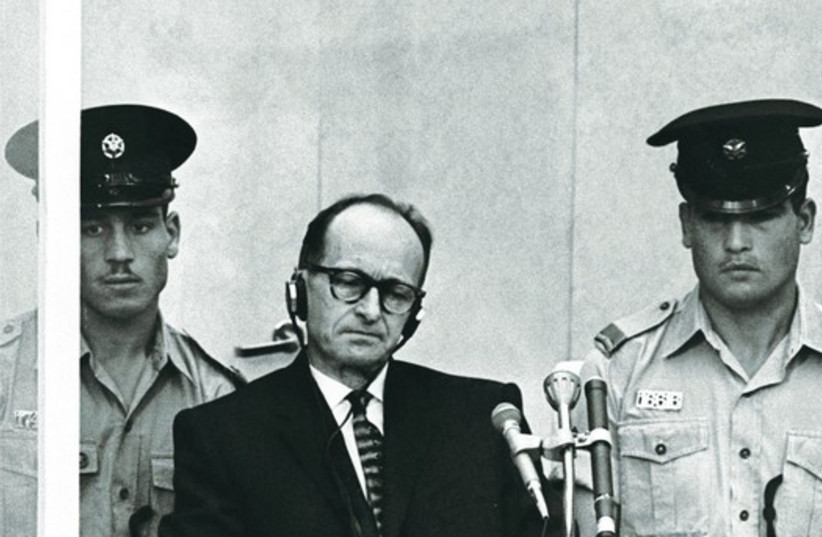

June Zero presents three stories that are connected thematically and create a vivid portrait of the diversity of life in Israel in the early ’60s. We know that Eichmann, the notorious Nazi commander who was responsible for implementing the Final Solution and causing the deaths of millions of Jews, was hanged outside a Ramla prison on June 1, 1962.

However, people forget that he spent about two years in Israel, as investigators interrogated him before the trial, during his trial, and in the period of appeals that followed the trial. There was a great fear on the part of the government – a justified fear – that a concentration camp survivor might assassinate him as revenge for the murders of their families. Since the vast majority of Holocaust victims were Ashkenazim, only Mizrahi police were allowed to guard Eichmann, and the movie focuses on Haim (Yoav Levi), his Moroccan-born main guard.

We hear Eichmann speak and see his feet and other parts of his body – such as his neck, in a harrowing scene when he is getting his hair cut and Haim worries that the barber will try to slit his throat – but he is not a character in the film. Instead, we identify with Haim who faithfully carries out the bizarre task of ensuring that no harm comes to one of the most notorious war criminals in history.

Other stories portrayed in the film

ANOTHER STORY features David (Noam Ovadia), a mischievous 13-year-old immigrant from Libya, who has been sent to work part-time in a factory run by a gruff owner (Tzahi Grad). This factory is given the assignment to build an oven for cremation, a method of body disposal not used in Israel since both Jewish and Muslim religious law prohibits its use. The idea was to cremate Eichmann’s body and scatter the ashes outside Israel’s territorial waters, so there would be no grave that could become a spot where pro-Nazis could make pilgrimages to. For the factory and its staff, it was a race against time to create this oven that is unlike anything they have ever made before, and they are aided by David’s boldness and by the thoroughness of a survivor (Ami Smolarchik), who struggles with his memories.

The third section is set in Poland, as Micha (Tom Hagy), a young Holocaust survivor investigating Eichmann’s crimes, revisits the ghetto and other sites where he and his family suffered and tells his story to visitors from abroad. There he meets a representative (Joy Rieger) of an Israeli delegation and the two engage in debates over how best to commemorate the Holocaust. She is critical of dwelling too long on the details of what happened, while he feels it is his mission to tell his story to the world, and for all survivors to tell their stories.

In a statement released by the producers, Paltrow, who visited Israel many times to research the movie, said that he felt that it was urgent to tell stories from the Holocaust to a younger generation around the world who may not understand what really happened and that he wanted to tell stories people had not heard before.

“What distinguishes this film from other Holocaust films is the examination of the subject through the most obvious physical and political consequence of the Holocaust: the State of Israel. Israel is not only a country where Holocaust survivors and their descendants live, but its diversity creates a rare mosaic of cultures and origins. The Eichmann trial was a turning point in the young country’s understanding of the atrocities committed by the Nazis in Europe.”

While many films, both documentaries and dramas, have focused on the dramatic Eichmann trial in Jerusalem, Paltrow chose to start the movie after the end of the trial. “Our film is intended to lay the foundations for understanding the complexities of Israel, from the aftermath of the Holocaust to today. This is not the story of the survival of a people in crisis, it is the story of the identity crisis of a people after survival. And throughout it there is also laughter, there is happiness, there is sadness and tears, conflict and drama,” he said.

Tom Shoval spoke warmly and appreciatively about collaborating with Paltrow on the screenplay.

“Jake got interested in everything connected to the Eichmann trial, it was a way for him to connect to his Jewish roots and identity, it’s something he’s spoken about a lot.” Paltrow became very interested in Israel in the early ’60s, Shoval said, and after he read an article about the building of the oven, he knew it would be the centerpiece of the film.

PALTROW WAS visiting Israel to work on pre-production for the film when the COVID pandemic broke out, and he was stuck in Israel for a few weeks. He and Shoval used the time to fine-tune the script. Paltrow even filed paperwork to emigrate to Israel so that he could stay in the country to keep working.

“It was a long journey, filled with unexpected turns,” said Shoval. At first, they had planned the movie to be mainly about the building of the oven, but then they realized it needed to be a “panorama of Israeli stories of this period. This interested us and we found so many fascinating stories, we knew we needed to include them.”

The decision to move outside of Israel and back to Poland to tell Micha’s story was also important in their writing process.

“The movie is about memory and history, about what it is to bear witness to the past... Before the Eichmann trial, it wasn’t acceptable for Holocaust survivors to tell their stories in public in Israel...and it was at this moment when the survivors received a kind of validation of their experience. It was a turning point and we wanted to show a character who experiences this as part of the film.”

The wealth of stories they discovered “made it possible for us to present a varied wide-ranging portrait of Israel, to show the Ashkenazim and the Mizrahim, the secular and religious, the Jews and the Arabs, the survivors and those who weren’t in the Holocaust, and how it all came together in this story...” said Shoval.

“It’s a story that hasn’t been told before, and it was important to us to tell it.”