Israeli filmmaker Inbar Horesh met Russian actress Nataliya Olshanskaya on the latter’s birthday, so they ordered a bottle of wine. Olshanskaya proceeded to tell Horesh the story of how she immigrated to Israel after taking a Birthright trip.

Horesh was so inspired that she eventually turned a version of that story into a short film, with Olshanskaya playing a character similar to herself.

“It actually started quite by coincidence,” Horesh told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in November.

The resulting 25-minute short, titled “Birth Right,” has played at several Jewish film festivals this fall and will stream at the Other Israel fest, which starts Thursday night and is run by the Marlene Myerson Jewish Community Center in New York. Horesh, a 32-year-old Jerusalem native who has directed several short films, says she’s at work on the screenplay for a feature-length version.

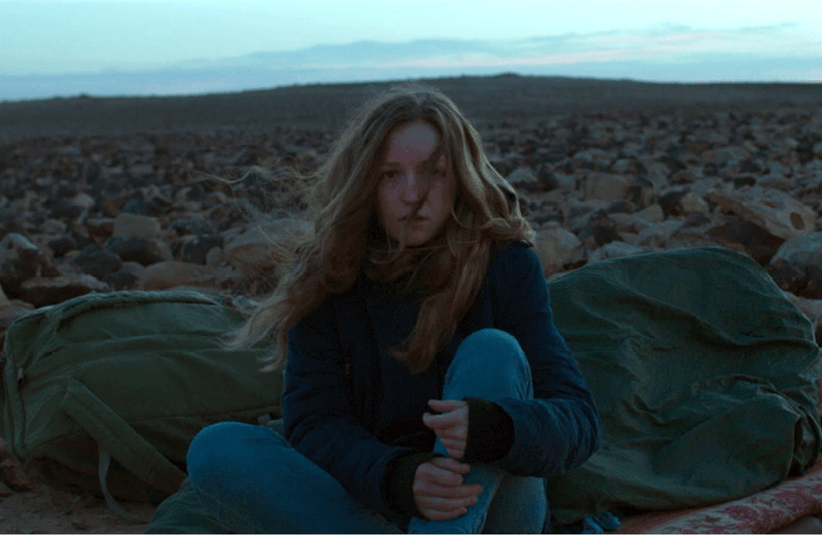

The film depicts a Birthright-style trip to Israel by a group of Russian speakers, focusing on the part of their visit to a Bedouin Arab village. Olshanskaya’s character, Natasha, banters with other young women on the trip and later bonds with a male Israeli soldier who also is of Russian heritage.

Eventually it becomes clear that Natasha, who plans to stay in Israel after the trip, is the child of a non-Jewish mother and doesn’t particularly identify as Jewish, and that her decision to emigrate has more to do with escaping a bad family situation than a sectarian desire to live in the Jewish state.

Under Israel’s laws, she’s eligible for citizenship — but once there, she will not be considered Jewish under the Chief Rabbinate’s rules on matrilineal descent.

For Horesh, the issues raised in the film speak to innate inequalities inherent in those laws.

“As an Israeli, what blew my mind was to realize that she doesn’t consider herself Jewish, and she didn’t grow up as Jewish, and yet she was approached by the Jewish Agency, invited to a trip, completely encouraged to emigrate to Israel, because she has Jewish heritage,” Horesh said.“To me it was surprising because I think as an Israeli, we have an image where we are the Jewish state, and we are not aware of the fact that actually the government is encouraging non-Jews to move to Israel — and my first instinct is to think that if the government is offering citizenship to non-Jews from outside of Israel, why not give citizenships to the non-Jews that already live in Israel?”

The film also tackles the sexualized undertones of Birthright trips, including the tradition of female participants having their pictures taken with gun-toting male soldiers. Jon Stewart joked about it in a 1996 stand-up routine, and a 2016 episode of the Comedy Central series “Broad City” depicted Birthright as a thinly veiled scheme to pressure young Jews to couple off, hook up, and eventually marry and reproduce.

“I was surprised to realize that one of the many ways to lure participants to join these types of trips is by creating this myth that these trips are full of sexuality, and [they’ll be] meeting young soldiers,” Horesh said. “And when you go out to a trip like this, you really realize that this is a very big part of the experience, that people are actually coming on these trips so men and women can meet each other. It’s actually part of the agenda in a very formal way.

“It creates this amazing gap between the very weighty Jewish content and the atmosphere of spring break.”

American audiences may be familiar with the American views of Birthright, but Horesh’s film presents an Israeli perspective, and one that focuses on a Russian person rather than an American. She says the film isn’t particularly meant as a takedown or broadside against the Birthright program itself.

“I have no specific criticism of the Birthright organization,” Horesh said. “I feel that as an Israeli, that doesn’t touch me so much. For me, my main interest is to look at the Israeli society and to examine how we define our identity. What does it mean to be Israeli?”

“Birth Right” was filmed in a “Bedouin camp for tourists” in the Negev, long before the start of the coronavirus pandemic, and it was produced with the assistance of the Israeli Film Council and the Ministry of Culture and Sport. It ends with a catchy, klezmer-style Russian-language song whose title, per the director, translates to “Dunia’s Head Began To Ache.”

While the film was shown in theaters at some festivals in Israel prior to the pandemic, it’s mostly been relegated to virtual festivals. It’s won awards, including the 2020 Moulin d’Ande Award at Cinemed: Montpellier International Festival of Mediterranean Cinema, and the award for Oscar-Qualifying Best Live Action Over 15 Minutes Award at the Palm Springs ShortFest.

There aren’t any specific plans yet to roll out the film for non-festival American audiences online, but Horesh hopes viewers eventually look beyond surface commentary on whether the film portrays Birthright as “good” or “bad.”

“I live in Israel, I grew up in Israel, I deal with Israeli issues more than with Jewish issues on a global scale. And for me,” she said, “the main idea is to help the people in Israel to realize that these definitions of who is Jewish and who is not, and who is allowed to be a part of the Jewish state, are not God-given, they are man-made.”