“Yet, Begin overestimated the change,” writes Emmanuel Navon, author of The Star and the Scepter: A Diplomatic History of Israel. “In 1981 the Reagan administration signed a ‘Memorandum of Understanding on Strategic Cooperation’ with Israel, an agreement that established joint military exercises.” This helped anchor US-Israel cooperation. However, even though the US wanted Israel to help deter the Soviets through this agreement, the US was also selling advanced AWACS fighter jets to Saudi Arabia. “Israel was concerned by America’s delivery of technologically advanced fighter jets to Saudi Arabia, an Arab country officially at war with Israel.”

US interests in the Middle East did not rely on Israel alone, the author writes.

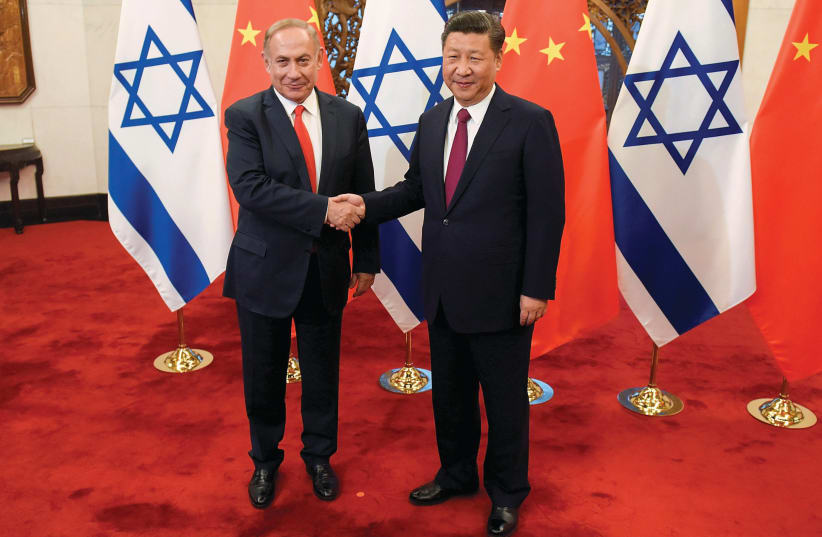

These lines, with some changes to reflect the Abraham Accords and Saudi Arabia’s stance, could be written today. Israel is a strategic partner of the US, but the US doesn’t rely on Israel alone. In America’s recent confrontation with China, Israel might be put in the middle.

Navon’s new book is a welcome, accessible and readable contribution to our understanding of Israel’s history and the Jewish people’s history in general.

The book retraces the Jews’ interactions with other nations, from the ancient Kingdom of Israel to the modern State of Israel today, Navon writes.

This is an ambitious goal. How do you write a whole diplomatic history of the Jewish people, from the time of the Bible to Israel? The sweeping story takes us from the period of the Jewish kingdoms to the Diaspora and the Zionist movement. With parts three and four of the book, a dozen chapters cover Israel’s diplomatic history after 1948 and then Israel’s relations with various parts of the world.

Because of the vast span of history that Navon seeks to cover, some of the key developments, such as Israel’s early diplomatic initiatives as it was founded and faced formidable obstacles, cannot be covered in depth.

However, Navon navigates this by providing insight into some of the key debates in Israeli diplomatic history.

For instance, when Israel was founded there was a key question about whether the country should be neutral in the emerging Cold War. A key event for Israel came during the Korean War. In July of 1950 prime minister David Ben-Gurion announced that Israel would condemn North Korea’s invasion of South Korea. Israel’s left-leaning parties, Mapam and Maki, urged the government against taking a stance.

In retrospect, it seems natural that Israel would side with the West and the US. However, at the time, the Soviet Union had recognized Israel, and there were many who felt Israel could find commonality with the Eastern Bloc.

While Israel chose the right side, it also meant it would be isolated from the Soviet-backed states and the nonaligned countries. Later the Soviet Union would provide key support and excuses for terrorists and enemy states that targeted Israel. It has taken Israel many decades to now achieve amicable and warmer relations with countries like Russia and India, which were tougher on Israel in the Cold War period.

Navon also navigates complex issues, such as Israel’s connection to the Diaspora and particularly divides between left-leaning US Jews and Israeli Jews. He notes how US support for a peace process dates back decades. The divide today operates, on many levels. It includes both disputes about the peace process and religious issues.

“For most Israelis, these social and religious issues are less important than security,” the author writes. Israelis don’t think a two-state solution is feasible at the moment. They also have a lot more to lose by experimenting with any kind of deal that might jeopardize security, as happened in Gaza when Hamas took over. Americans who support peace don’t have to deal with the consequences the same way.

When it comes to peace, Navon presents convincing evidence of just how quickly the Oslo Accords actually reached a political dead end in the 1990s. The Palestinian leadership did not seek peace, and despite Ehud Barak’s willingness to make far-reaching concessions, there was no progress. The Palestinians gambled on a war against Israel, called the Second Intifada, and lost. But it was a near-run affair with massive casualties.

Unfortunately the Oslo concept, a product of the optimism of the 1990s when the US was a global hegemon and democracy was supposed to be breaking out everywhere, didn’t work, and there is now a frozen conflict between Israel and the Palestinians.

Navon’s deft analysis and explanation of Israel’s relations with Asian states, its diplomatic initiatives in Africa, Latin America and the Arab world, make this book impressive and timely. These short but important chapters, as well as a discussion about Israel’s energy discoveries off the coast and how they shape Israel’s new friendships in the Eastern Mediterranean, are important.

An updated chapter on Israel’s new relations with Bahrain and the UAE and how they may shape the region would help this book. However, like all books on Israel and the region, the rapid developments in the region always leave more updates to come.

This book provides a welcome sweeping history of Israel, Zionism and the Jewish people in relation to diplomatic affairs.

THE STAR AND THE SCEPTER: A DIPLOMATIC HISTORY OF ISRAEL

By Emmanuel Navon

University of Nebraska Press

507 pages; $36.95