Hanukkah is the miracle season – and Susie Sheiner, 71, was hoping for a miracle of her own.

She wanted to go back home – but that’s not happening as soon as she would like. Sheiner’s home is one of the 60-plus houses in her moshav that were devastated by fire on Lag Ba’omer in May 2019.

Sheiner was one of the early residents of moshav Meor Modi’im – more commonly known as Mevo Modi’im – the cooperative village to which Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach brought a small group of members of his flock of “holy hippelech” from the House of Love and Prayer in San Francisco in 1975 to the ancient terrain of the Maccabees.

The Jewish Agency allocated to them a small, abandoned moshav that over time became home to three generations of Carlebach followers.

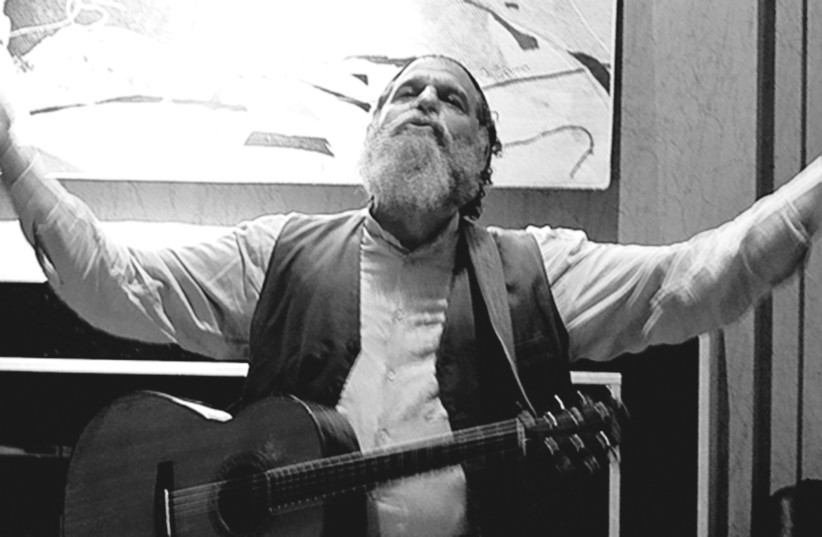

Carlebach spent considerable time there whenever he was in Israel, a truly beloved figure held not in awe but in respect and affection. Nearly every baby born on the moshav had at some stage been held on his knee. Jews of every stripe found their way to the moshav for a Shabbat or to celebrate Passover or Sukkot. There was an aura there that one did not find anywhere else in Israel. Nothing could quite equal Carlebach’s charismatic character, his gift for storytelling in which there was always a humane moral, and the way in which he inspired people around him to lift their voices in song, singing verses from Psalms and the Bible.

Sheiner and her husband arrived there 36 years ago, bringing with them a Torah scroll to place in the moshav synagogue that miraculously survived the Lag Ba’omer fire.

All that was left of most of the other buildings on the moshav were burned-out shells, blackened as if in mourning for what had once been there.

Like many of the hippies who had discovered and drawn closer to their Jewish identities through Carlebach, Sheiner and her husband had been far removed from religious observance before they got to the House of Love and Prayer. In fact, he had not even been born Jewish.

The New York-born Sheiner, when 20 years old, was on a trip to Israel and Europe. While traveling on a train in Naples, she met a young man by the name of Luciano. The mutual attraction was instant.

She went home to her mother in New York. He followed. They got married and went to study at a college in Miami. Luciano eventually converted, and became more Jewish than many who are born into the faith. An inventor, entrepreneur and social media guru, he has been known as Eliahu Gal-Or for the major part of his life.

Although Sheiner has a degree in occupational therapy, career-wise, she opted to run a pizza parlor, which not surprisingly was called Luciano. The name stayed put, even after she and her husband were divorced.

Both remained on the moshav after the divorce, and it was Eliahu who introduced her to her present husband, Shimon Sheiner, who was not a resident of the moshav but who lived in Jerusalem. He had come to the moshav one weekend for Shabbat, and a year later she bumped into him on a street corner and they fell in love. They’ve been together for seven years.

Susie and Eliahu who are now both in their seventies had six children. Two of their married children who lived on the moshav lost their houses in the fire. All that was left of Sheiner’s own three-bedroom house was a shell.

With one tragedy on top of another – a daughter died recently – Sheiner’s faith was sorely tested.

“I had to constantly be in a state of emunah,” she says, referring to the belief in a brighter tomorrow that has kept her strong, kept her going, and enabled her at age 69 to begin a new life. Unlike many of her generation, she did not have the luxury of retirement.

WHILE THE government subsidized the monthly rental fee on her temporary apartment in Hashmonaim, where she and her present husband reside, this aid package will cease in February 2022, and Sheiner will have to become totally self-reliant.

In Hashmonaim, she reopened her Luciano restaurant and is delighted to also have the company of her cat Sir Lancelot, who somehow escaped the fire.

In the beginning, Hashmonaim was new and exciting. Its resident population was friendly and welcoming, and Sheiner breathed a sigh of relief that she had been able to save the tables of her former restaurant and bring them with her, thereby saving on the expenditure of having to buy new ones.

The pizza parlor that she opened there is doing reasonably well considering the circumstances, and the hesitation of some people to eat in restaurants. But young courting couples looking for a place to meet that is simultaneously open, yet private and inexpensive, do tend to come and spend time there.

Sheiner has hired a contractor to start working on her house in Mevo Modi’im, but does not yet have the financial means that will enable him to complete the job. She was able to get started because she had been left something in the will of a deceased relative, but she’s not making enough money out of her restaurant – which serves not only pizza but other Italian favorites – to give him a sufficient lump sum at this stage. So she will be staying in Hashmonaim longer than she intended.

Although she likes Hashmonaim and has made many friends there, it’s not home, and she’s yearning to go back to her own house.

When that eventually happens, the moshav will not be as it was. The founding residents and the first-generation born on the moshav may be the same, and still very much part of an extended family even though they have not been living together for the past two-and-a-half years. But the burned-out surroundings will be different despite nature being relatively swift in recovering from traumatic events.

The future will also be different. An issue that the moshav residents had with the Israel Lands Authority over land rights has been settled by compromise. The moshav is to be enlarged and will accommodate an additional 120-150 families. Construction will take at least four years, and visitors will find a somewhat different atmosphere from what prevailed before the fire. Future plans include the development of a 100-room hotel, which will provide members with a steady income; and a Shlomo Carlebach Health and Education Center, where Carlebach’s legacy as a teacher and singer will be preserved.

But institutionalized Carlebach will not be quite the same as spontaneous Carlebach. Regular in-person events such as the monthly Rosh Hodesh gatherings for women, and the Moshav Country Fair on Passover that used to bring large numbers of individuals and families to the moshav are now held on social media platforms. Although the entertainment is by familiar figures such as Benzion Solomon, Yehuda Katz, The Moshav Band, the Solomon Brothers, Aharon Razel, Chaim Dovid Saracik and others whose repertoires are filled with Carlebach melodies, watching them on screen is not the same as joining with them when they sing on stage.

For all that, Sheiner’s homecoming, when it happens, won’t be an entirely transformed place. Several families whose houses were not destroyed, or only slightly damaged, have already returned, so there will be some familiar faces. The slogan for those who were evacuated is “‘Return, Rebuild, Restore,” and most, like Sheiner, intend to live up to that.