We all have our secret fantasies about celebrities we would dearly love to meet and, maybe have a “cup o’ joe” or something stronger with, right?

Some might dream about a movie star, soccer player or some rock god. But those of a literary bent, from this part of the world, might be thinking more along the lines of Shai Agnon, Yehuda Amichai or even Aharon Applefeld.

If the latter is your closest predilection you can make good on that by simply trotting over to the Tmol Shilshom café in a picturesque back alley off Nahalat Shiva. OK, so none of the three esteemed gents is there in actual corporeal form, largely due to the fact that they have all passed on, but Rina Peled and Leora Wise are currently offering some sense of what it may have been like to pass by a table at their café of choice.

Peled and Wise are responsible for putting together the How Do You Want Your Coffee? exhibition currently on show at Tmol Shilshom, a loving homage to some of the cafés dotted around the triangle of downtown Jerusalem through the 1950-1970s. The original Hebrew title is Ness Oh Botz – Nescafe or Mud Coffee – which, to my mind, captures the yesteryear zeitgeist far more succinctly.

And an eye-catching display it is too, with the aforementioned table side papier-mâché literary giant triad, and replicas of all manner of mementos from those halcyon days when Jerusalem was awash with coffee houses that exuded character and heady cultural ambiance, not to mention the aroma of fine brews and an array of tasty mouthfuls.

The exhibition exhumes a veritable roll call of venerated cafes which most Jerusalemites over the age 50 or so will probably remember. Fink, Ta’amon, Atara, Tuv Ta’am, Nitzan, Alaska, Bacchus and Café Max all provided the public with quality coffee and tea, as well as various alcoholic beverages. The menus were largely based on epicurean delights the owners brought with them when they made aliyah from Germany, Austria, Hungary, Romania and other points across Central and East Asia.

The vittles offerings would probably have featured onion soup, pickled herring, cinnamon rolls, yeast cake and apple strudel, any of which could be washed down with a shot of Extra Fine or 777 brandy. All of the above, other than the Extra Fine which is no longer produced, can be knocked back at Tmol Shilshom from a menu especially created for the exhibition.

A facsimile of a menu from the Fink bar-restaurant, which did business on Histadrut Street, shows some fetching illustrations betwixt a limited dessert offering which includes “omelette soufflee, chocolate cream and compot,” (sic) at 200, 70 and 70 lira a piece, as well as “Drinks and Digestifs” and “Cocktails for. prod.” – the abbreviations stand for “foreign produce,” a rarity in pre-Soviet mass aliyah early 1990s Israel. The hot drinks section features – as befitting the exhibition’s Hebrew moniker – instant coffee and Turkish coffee, tea and Glühwein (spicy wine), with a couple of innovations of the day, Sanka decaffeinated coffee and filter coffee.

Fink also attracted some celebrity clientele, with feted American conductor Leonard Bernstein dropping by when he was in town, as did crooner Harry Belafonte. “Fink wasn’t exactly a café. But it was considered the finest bar in the Middle East,” said Wise. On two of his visits, in the 1950s, Bernstein left the owners with an autograph accompanied by a bar or two of his compositions, including his Symphony no. 1, aka Jeremiah.

ONE OF the monochrome prints in the wall display shows a middle-aged waitress striding purposefully down the aisle between diners’ tables at the Alaska café, on Jaffa Street near Zion Square. The tray she is holding, in her left hand, is at a perfect 180 degrees to the floor and she is impeccably decked out in a waitress uniform complete with white apron.

“That is how they dressed when my grandfather and, later, my father ran the place,” says Uri Greenspan, grandson of the original owner of Atara, Bernhard Greenspan, who fled Nazi Germany in 1938 and acquired a license for the café from the Tel Aviv-based chain.

Greenspan took over the business and ran it from Atara’s second home – it started on Jaffa Street – on Ben Yehuda Street from the 1970s through to a second relocation, this time to Azza Road, in 1996. They were different times, with very different rules of decorum and etiquette. “Being a waitress was not like it is today,” he recalls. “It was a proper, and respected, profession. We had wives of Foreign Ministry employees, lawyers and others who worked at our café. Waitresses spent a long time training for the job – on full pay – before they could take up the position.”

Some of Greenspan’s earliest memories are of his granddad’s place. “I was only small – I actually only know this from stories I was told – when I crawled straight into the cakes display window. I think I made quite a mess,” he laughed.

Men and women of letters were also regulars at downtown cafes, including the likes of Applefeld and Amos Oz. “Atara is mentioned in Oz’s book My Michael,” Greenspan noted. “I’m sure many writers were inspired by the ambiance and the people who sat in Atara.”

One of the quotes in the exhibition text cites Applefeld, saying: “I wrote all my works in cafés in Jerusalem... only in the café in Jerusalem do I feel freedom of the imagination.”

The old Knesset was just up the road from Atara, on King George Street, and that brought in business too. “That was the center of Jerusalem,” Greenspan added. “We had politicians, lawyers, businessmen, artists and actors among our clientele. When Habima [theater company] came over [from Tel Aviv] to perform at Edison (cinema, theater and concert hall) they’d come by the café beforehand. They had their own table, and they’d gossip away and drink their coffee. For me, all of that was an unforgettable experience.”

Greenspan mourns the death of the archetypal, European-style Jerusalem café. “We moved from Azza Road to Mevaseret Zion, and we carried on there for 10 years. But we couldn’t keep up with the changes of contemporary life, and we didn’t want to compromise our standards to such an extent. So we closed in 2011.” That is probably hard for regulars of the Aroma and Cofix chains to envisage.

As we get older it is easier to be wafted away on clouds of nostalgia, to a time when – seemingly – the world was a healthier and more manageable proposition. Peled believes she has the historical evidence that points to saner, more moral times.

“Back then, in the heyday of the Jerusalem café, there wasn’t the political polarization you have today. Ta’amon is an interesting phenomenon. Today you have all sorts of cliques, religious and secular people, and that sort of thing.”

Not that Ta’amon didn’t have its fair share of spats. The café was located right across the road from the Knesset on King George Street, and was frequented by many media professionals, as well as academics, artists and members of the Black Panther protest movement from Musrara. Interestingly, the owner, a sixth-generation Jerusalemite called Mordechai Kopp was a hard line right winger while many of his clients were firmly on the Left side of the political divide. That evoked many a robust debate but no one ever came to fisticuffs. “It was different back then. Ta’amon was a left-wing stronghold,” Peled explained. “Two political movements, Matzpen, which was radically left-wing, and the Black Panthers started there. They’d hold their ‘parliaments’ in the café.”

ALL THIS is a far cry from the Vienna Café, down on Zion Square, and its ilk which were spawned by the presence of British soldiers during the Mandate era, and which often hosted classical music recitals, and even dances with jazz bands.

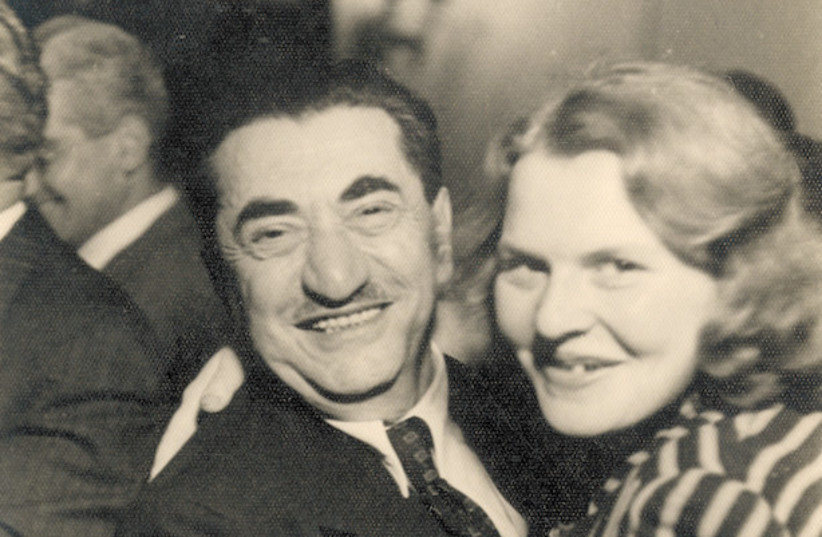

Reuven Milon remembers those times. The 93-year-old Jerusalem-born photographer has a couple of shots in the Tmol Shilshom exhibition. One shows three men sitting at a table at the Nitzan Café which, when the picture was taken in 1953, was in the upper regions of Ben Yehuda Street. Milon himself was a fixture there. “I was a student at Bezalel,” he recalled. The original art school was founded in a building on Shmuel Hanagid Street, where the Jerusalem Artists House and the neighboring old building now stand. “I used to go to Nitzan for coffee and a bite to eat. It was the closest to the school.”

There was an ulterior motive. “Nitzan was full of students. The teachers normally went to a café called Tzilla. So I guess that’s why we chose a different café,” he chuckled.

Nitzan also had its own dynamics, and often hosted fiery discussions. “I remember there were student protests there, outside, against the black market and various social injustices. And there was political debate. There was a highly charged atmosphere there. It was exciting.”

Almost seven decades on Milon says he hankers after those good old days. “You had people like [journalist, poet and satirist] Didi Menosi who drank coffee, and hung out at Nitzan.” Menosi appears in the aforementioned print which seems to have been taken on a wintry Jerusalem day.

“I remember all those cafés and, until August, I used to go downtown as often as I could, to take pictures and walk around.” Unfortunately, Milon broke his leg a few months ago, but he appears to be on the mend and is looking forward to resuming his constitutionals around the old café route.

Peled notes that for many less well-heeled Jerusalemites, cafés offered a cozy logistical option. “A lot of people lived in small apartments, especially in the 1950s and 1960s, and often they were not very well heated in the winter. They could go to cafés and also get through work, like teachers marking papers and exams, and that sort of thing. They’d take a table upstairs in some café and stay there all day for the price of one cup of coffee.” That must have been hard on some café owners’ cash flows, but they all somehow survived.

That is still the case today, although the reams of students’ papers and books have been replaced by far more compact laptop computers. That is not the only change in café clientele aesthetics. “Women used to have their hair done, and put on their best clothes, just to go to a café,” Wise explained. “For women, going out to a café was a real occasion.”

How times have changed. Twenty-first-century café culture is a very different beast to the establishments opened here in Jerusalem’s downtown triangle that transposed the ambiance of 1930s Berlin or Vienna to the Middle East.

With its literary roots, and paving stone floor, Tmol Shilshom is a worthy custodian – albeit temporary – of a blast from a more genteel past.

How Do You Want Your Coffee? closes on December 31.

Details: (02) 623-2758 and www.tmol-shilshom.co.il