It can be a tricky business getting a good photo with a commensurate story line.

You have to make sure your exposure settings are spot-on, and then there’s the frame composition. And, if you’re talking pre-digital camera era, it is a completely different, less technologically precise or preset ballgame which demands a range of skills and intuition which most of us, in the cellphone camera age, sorely lack.

Aviv Itzhaky pertains to that time, when you clicked a release button, heard the sound of an actual mechanical shutter rapidly opening and closing, and then waited to see what you captured in your lens.

Some of the fruits of his tireless beat pounding, across all corners of Jerusalem, in the 1970s, with intermittent forays in the following decade, are currently on show in the “My Jerusalem” exhibition at the Jerusalem International Convention Center (ICC), under the curatorship of Eran Litvin.

Now in his early seventies, the Bayit Vagan resident’s work reflects an intriguing insider-outsider viewpoint on quotidian events and developments in the city. He was born in Haifa but relocated to Jerusalem to further his arts education.

“I studied graphics at Bezalel [Academy of Arts and Design],” he recalls. “At the time the academy didn’t have a full program in photography, only one course.”

The latter was given by a teacher from Britain, and Itzhaky found the confluence particularly beneficial, and got some valuable hands-on experience. “I got a lot from that course, and I started working, as an assistant, in the photography lab.”

In fact, he reaped a lot more than he’d bargained for from his time in Jerusalem, which spanned the whole of the 1970s. He came out of the decade with a new career path and a complete change in lifestyle and familial circumstances.

“I stayed on after my studies at Bezalel, and then, around the mid-’70s, I met Catherine, who later became my wife. She came here from France to attend ulpan.”

The mademoiselle had a daytime job in the media, and Itzhaky soon found himself tagging along on her assignments. It was an offer he found hard to refuse, for a variety of reasons.

“I didn’t really know what I wanted to do with my life, so I joined her,” he laughs. “It was an opportunity to get some idea of what journalistic photography is all about. That’s how I got dragged into the field. I’d never dreamt of being a press photographer.”

Itzhaky proved to have an eye for documentary image snapping. The professional synergy went well, and the personal chemistry was also moving along nicely. The two got married, and the Haifa-born, Jerusalem-resident photographer moved to Paris with his new wife, had a family and stayed for 33 years.

Back in Jerusalem for almost a decade now, Itzhaky is delighted to have the opportunity to share some of the sights and street-level vibes he saw and documented during his pre-France furlough in Jerusalem, with some added items from his annual summer jaunts here, in the 1980s. “In France I worked with various Jewish publications, and when I visited Israel I’d take pictures of everyday life.”

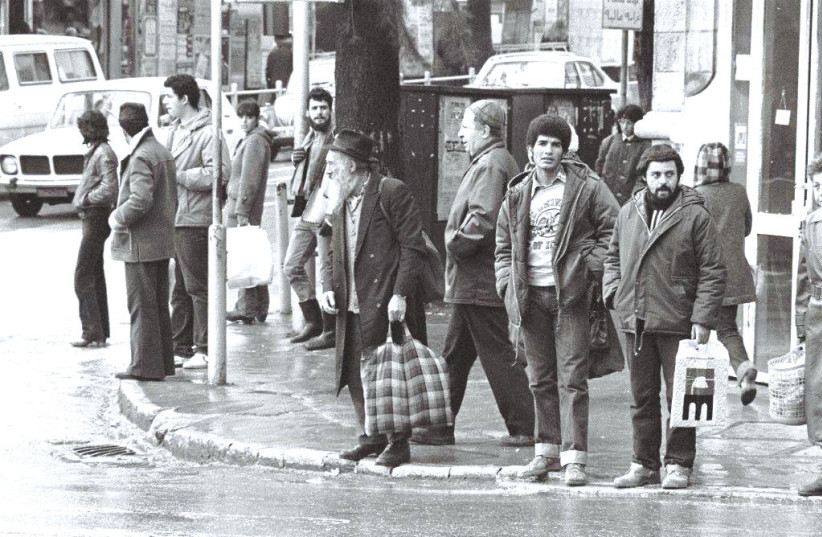

That down and dirty take comes across in “My Jerusalem,” which includes shots of pre-pedestrian mall Ben-Yehuda Street, an almost unrecognizable Zion Square, and a couple of quirky shots of Independence Park and Yemin Moshe.

Itzhaky has a discerning photographer’s eye for alluring incidents and composition. “I was never really drawn to current affairs, to official events. I like to photograph everyday life. That’s what interests me.”

Arriving in Jerusalem in late 1970, he was in the capital during the turbulent days of the Black Panther social protests in Musrara and elsewhere, which attracted snappers of all ilks, including journalists from abroad. But that wasn’t Itzhaky’s cup of tea.

“That didn’t appeal to me,” he says, while noting he didn’t entirely eschew politically related events. “I sometimes took pictures of demonstrations, although maybe not the Panthers themselves. I’m not into politics.”

Then again, some dramatic – even traumatic – personal experiences did briefly pull him over to the political side of the tracks. “I was a reserve duty soldier in the Yom Kippur War and I participated in some peace protests, of the Peace Now movement and such like.”

Still, Itzhaky is not one for milling around crowds. “I have never liked attending events with large numbers of people, but I took photos at some of the protests.”

But that was strictly on a personal basis. “I didn’t want to publish any of the pictures. That wasn’t my thing.”

The battlefield left its scars on Itzhaky. “I didn’t have combat stress, but the war shook up my life completely. I had a crisis of ideology. I came from a Mapainik family, and I had the feeling that the political leadership had betrayed us, and there was the so-called battle of the generals, who quarreled among themselves about the way the war should be fought.”

After being demobbed Itzhaky returned to Bezalel a different person. “In my final year I split my time between the cafeteria and the library. I left the academy without a degree. I didn’t fulfill all the requirements for that.”

Absence of official graduation certificate notwithstanding, Itzhaky enjoyed his fly-on-the-wall excursions around the streets of the city, and his keen sense of humor frequently came to the fore.

One print in the exhibition, taken in downtown Jerusalem in 1972, shows a newspaper vendor with a pile of papers on the sidewalk, while another heap provides him with a comfortable pew.

“Look, he’s reading the stuff he sells,” Itzhaky laughs.

Veteran Jerusalemites and anyone who has visited the city over the years should get a kick out of the prints, which show a world that has long since gone. The structural urban changes have gathered pace over time, and certainly since work began on the light rail in 2002.

For newcomers it is hard to imagine the modest city skyline of the seventies, as today building sites of tower blocks proliferate across the center of town.

One of the Itzhaky prints that did not make it into the ICC spread shows the oft-maligned Clal Building under construction with a crane towering over it.

“The city started developing after the Six Day War,” Itzhaky notes. And he was around to document much of it.

ITZHAKY FELL in love with snapping at an early age, and received parental encouragement to follow his artistic muse.

“I’ve always had an artistic bent,” he says. “I drew and sketched when I was small, and I began taking pictures with my father’s 6x6 German camera. It was a Voigtlander Brilliant.” Not a bad piece of equipment to start out on.

The kid was keen and was allowed to pursue his newfound love. “They sent me on a photography course at Beit Hagefen [in Haifa]. I learned how to develop film there. So I had the technical skills, and my pathway into photography was set.”

Later he hooked up with the aforementioned Bezalel teacher and got his own camera, a Pentax Spotmatic fixed lens 35 mm. job. “That was a pretty good camera which served me well for quite a few years.”

And the proof of that loyal service is currently hanging on the walls of the ICC building.

“That was a prolific time for me [in 1970s Jerusalem]. I took lots of pictures, and I had fun with that. When I look back at the photos I took back then, I can see they are pretty good.” That was, he explains, not just a matter of using his hard-earned technical expertise. It was a labor of love. “I enjoyed what I was doing.”

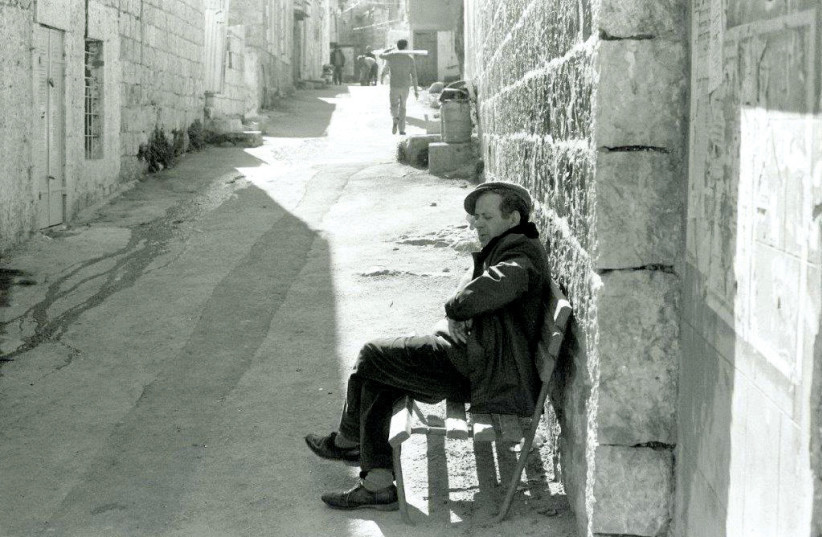

That followed something of an evolutionary thematic continuum, as Itzhaky gravitated toward the more human side of the city.

“At the beginning I took pictures of buildings. I had an artist’s eye in terms of noticing shapes and forms, and spaces. I took photos of street corners and buildings. Abandoned buildings also caught my eye, although I didn’t really know why. Maybe it was the dimension of time that comes across in the textures, but I wasn’t really conscious of that.”

The wrench from everyday life, caused by his extended military tour in 1973, also helped Itzhaky to change and direct his – pardon the pun – focus on the human landscape of the city, rather than its bricks, mortar and stone.

The war also curtailed a confluence with bona fide photography royalty.

“When I was a student at Bezalel, Cornell Capa came to visit,” Itzhaky recalls.

The VIP guest was the brother of iconic war photographer Robert Capa, and was a celebrated global snapper himself.

“He invited some of us to take part in a project with him. But the Yom Kippur war started, I left for reserves, and that was the end of that.” It was not a complete downer. “During the interim I had time to consider my approach to photography, and I realized I was more interested in people than in buildings.”

There are plenty of both in “My Jerusalem.” And, although for anyone who remembers the much smaller, quieter and less ambitious city of yesteryear, some of the prints will undoubtedly evoke some sentimental feelings, it is the characters that people Itzhaky’s pictures that really catch the viewer’s eye and heart.

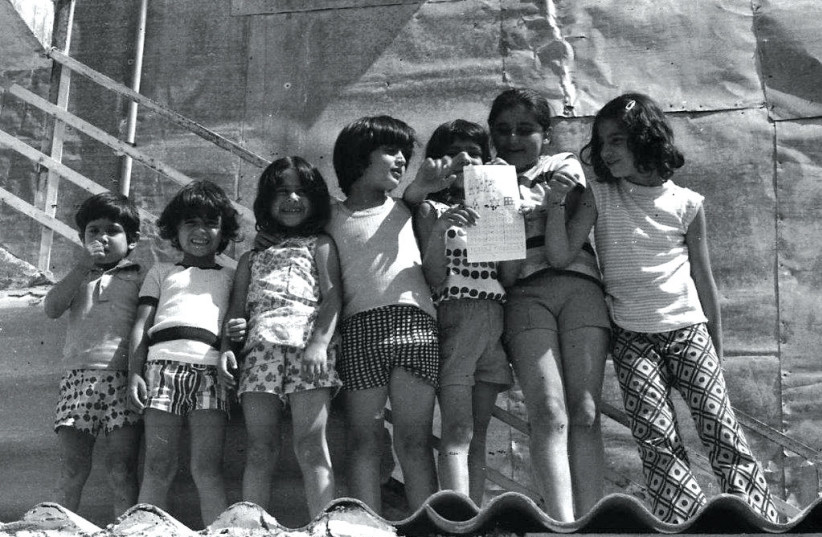

The 1971 “Kids of Nahlaot” work is a joy to behold, as is “Boys Selling Newspapers” taken a couple of years later on Agrippas Street, and the 1974 shot of satchel-strapped tiny tots leaving school on a winter’s day on Yeshayahu Street near Mea She’arim.

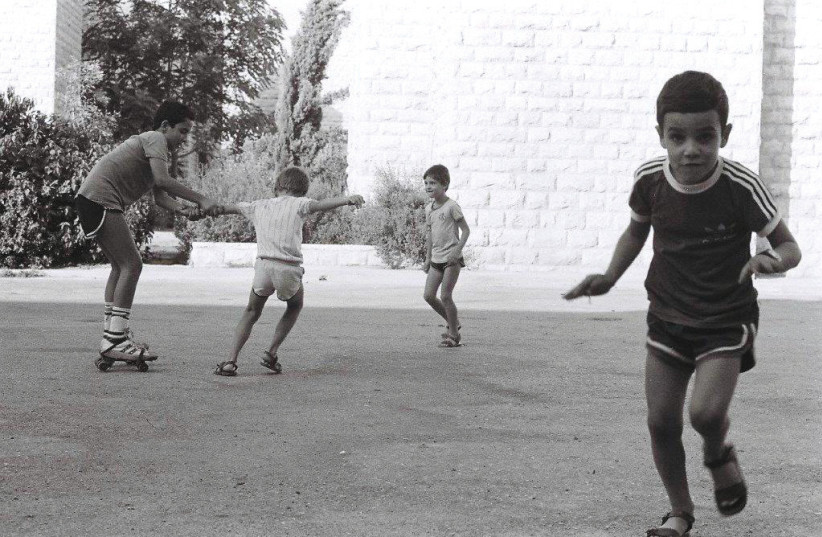

“Outside the Bank” on Ben-Yehuda Street in 1978 is a blast from the past, back in the pre-Internet day when you had to read a newspaper, or pop by a bank to get the latest foreign exchange rates or stock market prices. “Children Playing, Town Center,” also from 1978, shot on Agron Street, exudes youthful insouciance and is also something of a surreal offering.

ITZHAKY SAYS he is always open to ideas and inspiration.

I recalled the delightful 1995 Wayne Wang-Paul Auster movie Smoke and the character played by Harvey Keitel, who set up his camera outside his tobacconist store every single day and took one shot from the same spot, from the same angle, at exactly the same time. That opened me up to the simple idea of waiting for the action to enter your lens’ field of vision rather than hunting for it.

“I do that sometimes,” says Itzhaky, “if I find a good location where I expect things might happen.”

Naturally, getting a good picture is often the result of being in the right place at the right time. For a while, Itzhaky lived in Yemin Moshe and was around while the old neighborhood was being demolished to make way for newer, more attractive, buildings. “Demolition at Yemin Moshe,” from 1975, shows the last vestiges of a building, an ornate upstairs balcony, seemingly hanging on by a final thread.

“I just happened to be there and saw that, Itzhaky says matter-of-factly. “I think it’s a good shot.” It certainly is.

Keeping his practiced eyes peeled is, by now, second nature for him, as he continues to capture Jerusalem life around him. “I’m not busy with a particular project right now, but, you know, if I see something interesting I take a picture.”

As there is generally constantly “something interesting” happening in Jerusalem, perhaps we will be able to enjoy some more intriguing, entertaining and evocative pictures by Itzhaky before too long.