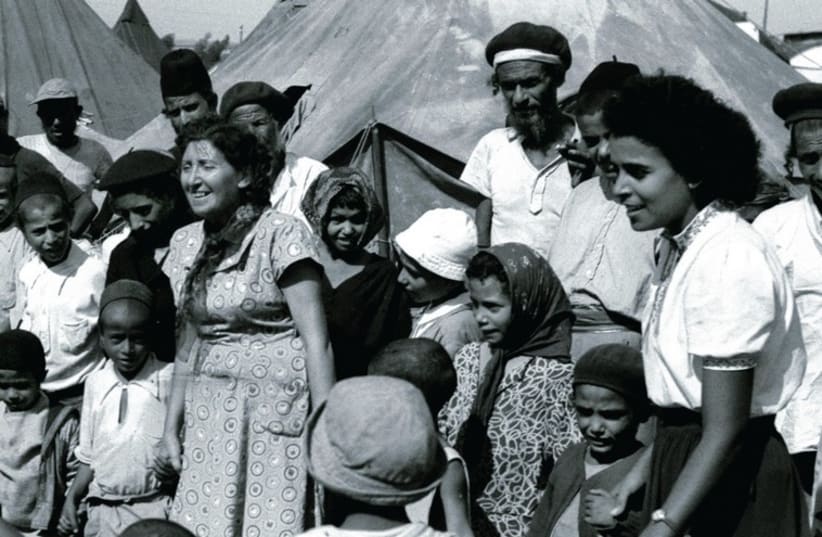

Travails of Jews from Arab Lands finally recognized after 66 years

The intention behind the bill, said one of the bill's makers, was to ensure that the stories of what happened to Jews in and from Arab lands and Iran should be part of the school curriculum.