I made Peter Bogdanovich nervous.

The director, who died last Thursday at 82, took the movie industry by storm with three hugely successful feature films – both critically and commercially – in the early 1970s, The Last Picture Show (1971), What’s Up, Doc? (1972) and Paper Moon (1973), that helped redefine American cinema. But in 1999, when I interviewed him for the New York Post, he had fallen on hard times and for decades he had been in the gossip columns more than the arts pages.

That was why I made him nervous. The New York Post was famous for its gossip columns and gossip columnists (notably Page Six and Cindy Adams), and he was afraid I would write a lurid piece about his marriage to Louise Stratten, who was 29 years his junior and whom he had met when she was 11.

She was the younger sister of Dorothy Stratten, the Playboy playmate he fell in love with and tried to turn into a movie star by casting her in his rom-com, They All Laughed (1981). Dorothy Stratten was murdered at age 20 by her estranged husband, Paul Snider, who then killed himself.

In subsequent articles and films about the starlet – including Bob Fosse’s Star 80 – Bogdanovich was portrayed as just one more man who had taken advantage of her. When Bogdanovich married Louise nine years later, it struck many as odd, if not creepy. Bogdanovich’s first marriage, to production designer Polly Platt, who worked closely with him on his early films, broke up after he left her for Cybill Shepherd, one of the stars of The Last Picture Show.

Briefly, Bogdanovich and Shepherd acted like the king and queen of the new Hollywood, until two films he made that she starred in, Daisy Miller and At Long Last Love, bombed. He never made a major movie again, except for Mask in 1985. Recently, he had been directing TV movies, a comedown for a filmmaker who had been hailed as a successor to Orson Welles.

WHEN I met with Bogdanovich at Zen Palate, an Asian restaurant on Broadway and 76th Street – we were both Upper West Siders born and bred – he was promoting a revival of his 1993 film, The Thing Called Love, a fun little movie about the country music business. It had a truncated release after its young star, River Phoenix, died of an overdose just after it was completed.

“A real tragedy,” he said in our interview. But although Phoenix had suffered an untimely death, some of its other actors, including Sandra Bullock and Dermot Mulroney, had become stars since it was made, and interest in the film had been rekindled.

He recalled that Phoenix had heard that he was making the movie and called to ask to be cast in it, since he had always wanted to sing in a movie. Phoenix actually agreed to star in it without even meeting Bogdanovich.

“The film probably wouldn’t have gotten made if River hadn’t gotten involved,” he acknowledged. In the summer of 1999, it was going to be shown for the first time in New York at the Anthology Film Archives in the East Village.

Before our meeting, the proprietors of the theater had assured Bogdanovich that he could trust me. I was a cinephile. I loved his work and would ask him about his movies, not his love life.

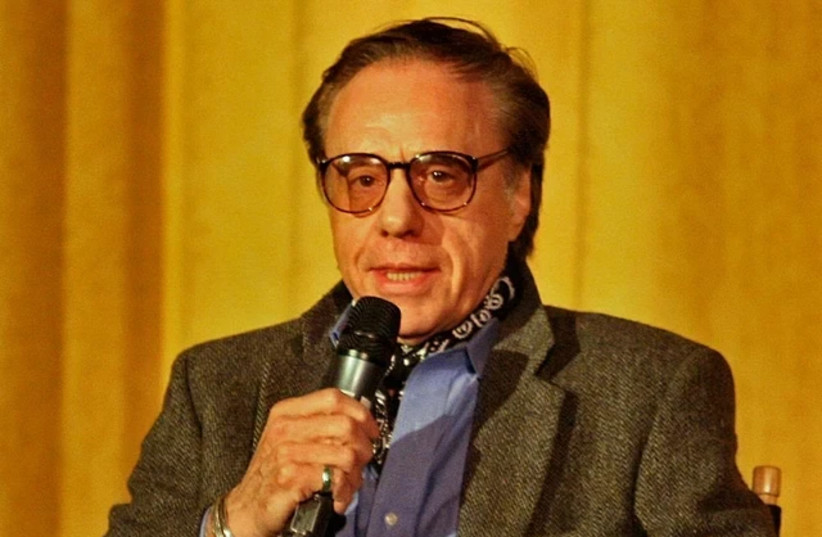

ALTHOUGH IT was July and one of the hottest days on record that summer, Bogdanovich arrived white as a sheet and wearing a suit and one of his trademark ascot ties. I was seven months pregnant but he didn’t remark on that, or even seem to notice. Not that there was anything wrong with his not saying anything, but since my pregnancy had started to show, it was usually a great icebreaker with interviewees.

With Bogdanovich, there was no way to break the ice. His face and body radiated tension. I ordered ice tea and he asked for water but didn’t touch it.

He was just about to embark on the acting gig for which he is best known to younger audiences, Dr. Elliot Kupferberg, Dr. Jennifer Melfi’s supervisor on The Sopranos, but he did not mention it. Playing Kupferberg, he had a dry, low-key humor and self assurance, but on that day in July, he seemed more like the nerdy teen cineaste who had been a programmer for the New Yorker arthouse theater, which had been located just a few blocks uptown, than a celebrated director/actor.

His parents were refugees from Hitler. His father, Borislav, was a Serbian painter who met his mother Herma, a refugee from an Austrian Jewish family, in Yugoslavia when she took art lessons from him after fleeing Vienna. They married in 1938 and moved to New York, where Bogdanovich was raised in a bohemian atmosphere on 90th Street and Riverside Drive.

Although his mother was Jewish, Bogdanovich’s religion was the movies. Toby Talbot, a founder of the New Yorker theater, a mecca for New York intellectuals, recalled in her memoir: “Peter Bogdanovich got off to a fast start. Shortly after the New Yorker opened, a young man of around 18 showed up. ‘I’m Peter Bogdanovich,’ he said. ‘I live across the street from you and I want a free pass and a job – not as an usher or a doorman but as a consultant.’”

He demonstrated his knowledge and was hired to write program notes for the theater, the beginning of a career as a film critic. But soon, just like young French film critics such as Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard had done a few years before, he became convinced he could make movies just as good as the ones he was writing about.

He and his first wife drove to Hollywood, where he found work directing low-budget pictures for Roger Corman, king of the B-movies. He joined an illustrious group working for Corman that included Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese and James Cameron.

By 1971, he had made The Last Picture Show, an adaptation of Larry McMurtry’s novel about a bleak Texas town in the 1950s, starring an amazing ensemble cast that included Jeff Bridges, Ellen Burstyn, Cloris Leachman and Ben Johnson, as well as Shepherd. It won two Oscars and holds up remarkably well today. Made when he was in his early 30s, it was compared favorably to Citizen Kane and will be remembered as his masterpiece.

Following the success of Paper Moon, for which Tatum O’Neal won an Oscar, he made several movies both with and without Shepherd, but couldn’t seem to catch a break in Hollywood. His only real success after that was Mask in 1985, although he feuded with its star, Cher, and the producers over changes they made.

But his love for movies remained strong and he said he did not mind making films for television, as he had been doing throughout the 1990s, which he described as a return to his low-budget roots. “It’s a healthier way to work, faster, more creative,” he told me. “You don’t just buy things, you figure out a way to do it.”

The headline on my 1999 article was, “His Last Picture Show,” but fortunately that turned out to be inaccurate. He made several more movies, including documentaries about Tom Petty and Buster Keaton, and a very good feature film, The Cat’s Meow (2001), about a murder on William Randolph Hearst’s yacht in 1924, starring Kirsten Dunst and Edward Herrmann, which deserves to be revived.

He also acted in a number of movies and television shows and wrote books. In 2019, he was interviewed by Vulture.com and was living in an apartment in Los Angeles with Louise Stratten, whom he had divorced in 2001, and her mother.

As we discussed his work, he began to relax and open up a little. He expressed sorrow that Dorothy Stratten’s murder had put the kibosh on They All Laughed, which also starred John Ritter as an alter-ego for the director, Audrey Hepburn (in one of her last roles), Ben Gazzara, Patti Hansen and Alexandra (Sashy) Bogdanovich, his daughter from his first marriage. It was an attempt to revive the screwball comedy genre, which he had done so successfully in What’s Up, Doc? nearly a decade before.

He had hoped it would make Stratten a star. The studio didn’t want to release it and he used his own money to get it into theaters, but it received mixed reviews – although directors such as Quentin Tarantino now consider it a cult classic – and did not earn much. But it was an important film for him.

“I feel closest to that film of all the films I’ve made,” he said. “If you want to find out who I am, that’s the movie to see.”