(JTA) — Before the hero of “Ahed’s Knee,” an Israeli filmmaker known only as “Y,” can screen one of his movies in a public library in an Arava desert town, he is told he must sign a document from Israel’s Ministry of Culture. The agreement states that, during his visit, he will only discuss with his audience a list of approved topics, including “Israeli history,” “the Holocaust,” ”family,” “love” and “comrades in arms.”

Examples of unapproved topics: Palestinians, the occupation and any suggestion that Israelis will tolerate dissent from their creative class.

This is a problem for Y (Avshalom Pollak). Not only is he prone to monologues about the sorry state of Israeli culture today, but he is also in production on a new movie — this one about the real-life Palestinian activist Ahed Tamimi. Jailed after slapping an Israeli soldier in 2017 during a clash in the West Bank, the teenager became a symbol of Palestinian resistance. (The film takes its title from a comment by an Israeli politician who said that Tamimi “should have gotten a bullet, at least in the kneecap,” to keep her under house arrest for life.)

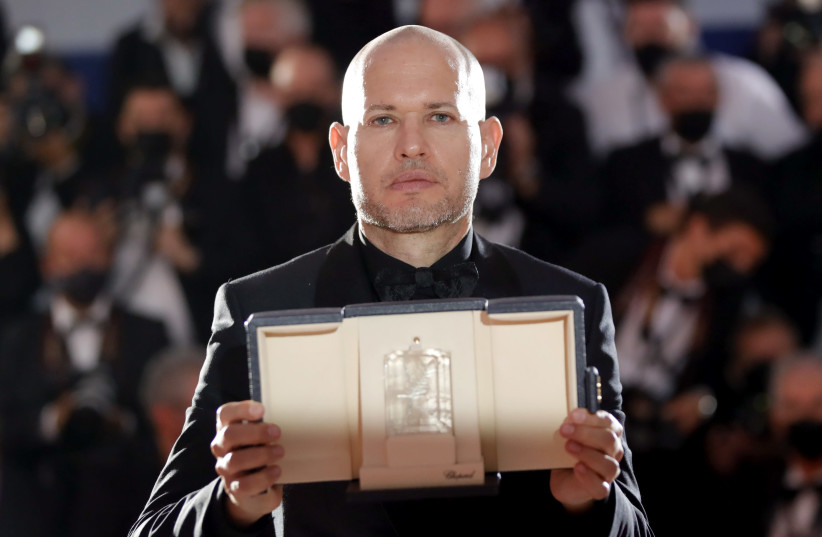

Winner of a special jury prize when it premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 2021, “Ahed’s Knee” is a work of fiction, although its writer-director Nadav Lapid is obviously channeling his own frustrations with working as a filmmaker in Israel. Lapid’s movies, which are frequently critical of nationalism and Israeli identity, are widely celebrated in art houses and film festivals around the world. His film “The Kindergarten Teacher” was remade into an American movie starring Maggie Gyllenhaal.

But on the basis of his latest film, it seems that Lapid has struggled to connect with audiences in Israel itself.

In “Ahed’s Knee,” Lapid’s avatar, Y, wanders through the desert town of Sapir prior to his film screening. He sends frequent photos and text messages to his unseen mother and collaborator, who is dying of cancer. (Lapid’s own mother, Era Lapid, was the editor of all of his previous films until she died from cancer in 2018; his father, Haim Lapid, is credited as a screenplay consultant on “Ahed’s Knee.”) While despairing that all his work has been for naught, and flashing back to traumatic experiences in the military that he may or may not have made up, Y enters an uneasy flirtation with his young escort, Yahalom (Nur Fibak), who works for the culture minister and has to compel the director to sign the approved topics agreement.

Though the minister in the film is never named, Lapid is likely taking shots at Miri Regev, Israel’s previous culture minister, who during her tenure under former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu insisted that the country should not be funding artwork that she deemed “disloyal” to the state. When Lapid’s film “Synonyms,” about an Israeli expat in Paris attempting to erase his national identity, won the Golden Bear at the 2019 Berlin Film Festival, Regev announced that no one in her ministry had seen the film.

Much of the events depicted in “Ahed’s Knee” are true, according to Lapid; in the film’s press notes, he says that he encountered a similar dilemma involving an “approved topics” form when he was invited to screen “The Kindergarten Teacher” in Sapir. Like his onscreen avatar, Lapid says he also encountered a young deputy culture minister who expressed serious misgivings about such forms even as she compelled him to sign one, and, as in the film, a journalist friend tried to get him to secretly record the civil servant making such comments. There’s a hint of self-deprecating humor in the way Lapid depicts Y as a blowhard and an egomaniac, while also making clear that the two are united in their political principles.

The movie explores a central tension between the artist and the state, a tension that has heightened significance in Israel, which aspires to be a democracy despite a constant state of heightened security and ideological tension. As Y weighs whether to blow up his entire career just to make a point, his own would-be professional suicide contrasts with other images of grand-scale destruction, like Sapir’s wilting bell pepper harvest, which used to sustain the village until climate change ruined farmers’ livelihoods.

In the spirit of many other film directors who make movies about themselves (Federico Fellini, Woody Allen, Hong Sang-soo and others), Lapid also offers no separation between the personal and the political. When Y rants that the culture ministry’s “sole aim is to reduce the soul … to impotence and incompetence so it collapses under the state’s oppression,” both directors, real and fictional, have boiled their frustrations down to only one message: the time for subtlety has passed.

“Ahed’s Knee” opens today in New York at Film at Lincoln Center, and expands across the country in the coming weeks.