In 1974, New York Times columnist John Corry could write confidently that “the Upper West Side … block for block, has more celebrated intellectuals than anywhere else in the city.” To prove it, he wrote about an annual gathering at 370 Riverside Drive, in an apartment overlooking the Hudson River.

“At Hannah Arendt’s New Year’s Eve party, West Side intellectuals with European backgrounds gather in one room, and West Side intellectuals with American backgrounds gather in another,” he wrote. “The Europeans are in the room with the liqueurs and chocolates. The Americans are in the room with the whisky.”

The idea of Hannah Arendt hosting raucous parties in a Manhattan apartment may come as a surprise to those who only know her as the German-Jewish exile whose brooding works include “The Origins of Totalitarianism,” “The Human Condition” and the still controversial “Eichmann in Jerusalem,” about the mastermind of the Final Solution.

But Arendt biographer Samantha Rose Hill also wants people to remember Arendt for what one of the philosopher’s closest friends, the novelist Mary McCarthy, called Arendt’s “skeptical wit” and “electric vitality.” To show this domestic side of a public intellectual, Hill devised a walking tour of Arendt’s Upper West Side, from the shabby first apartment where she landed almost penniless after fleeing Hitler’s Europe to that comfortable if indifferently decorated apartment 12A where she ladled out the liqueurs and whisky.

The self-guided version of the tour, narrated by Hill, has just been released through the Gesso app, in a collaboration with the Goethe-Institut New York, the cultural arm of the German government. Hill is the author of “Hannah Arendt” (Reaktion Books, 2021) and is editing an edition of Arendt’s poetry. On her podcast, “Between Worlds,” she talks with guests who have been touched by Arendt’s work.

“I like to think of this walk as a documentary,” Hill, who teaches at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research and the University of the Underground, says on the app. “Each stop mapping out a moment of Hannah Arendt’s life that unfolded in New York City between 1941, when she arrived as a stateless refugee, and her death in 1975. We are going to follow her footsteps to discover how she made a home in the United States.”

On a blustery Sunday afternoon, I joined Hill and a group of about 20 for an in-person version of the tour, beginning at the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument in Riverside Park. We continued in a loop that took in three of the places Arendt called home in the city — and four decades of the factious, haunted and distinctly Jewish history of the “New York Intellectuals,” the famed circle of mostly Jewish writers and literary critics.

The first stop, 317 W. 95th Street, is today a typically pricey condo, but on May 23, 1941, when Arendt and her second husband, Heinrich Blucher, arrived in New York, it was essentially a tenement for new immigrants. Arendt and Blucher were able to rent two rooms — one for them and one for her mother — with a $70 stipend from the Zionist Organization of America.

At this point in her life, Arendt was 35, and had established herself as a formidable political philosopher in a Germany that had no place for her. In 1933, she spent eight days as a prisoner of the Gestapo, jailed for the research into antisemitism she had done for the World Zionist Organization. Released, she fled to France, where she worked for Youth Aliyah, helping Jews immigrate to Palestine. She was detained again, and this time sent to a French internment camp. She walked out of the camp with forged papers, and with the help of the American journalist and freebooting diplomat Varian Fry, she was able to escape through Spain and Lisbon to New York.

No wonder, on the day she arrived at Ellis Island, she would telegram her first husband, Gunther Anders, saying, “We’re saved.”

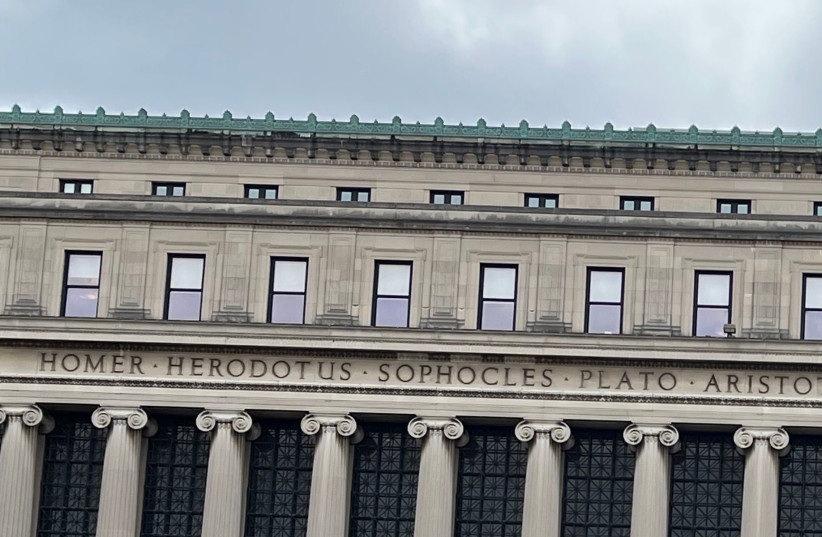

Arendt now had to establish herself in a new country and a different language — a process facilitated by her visits to the next stop on the walking tour: Columbia University. We covered the 19 blocks Arendt would have walked to the campus in about 25 minutes. Hill had us look at the names of the philosophers carved into the façade of the Butler Library: Homer, Herodotus, Sophocles, Plato. “These are the people that she fell in love with as a child, reading in her father’s library,” said Hill. “She would stand on a table and recite Homer in ancient Greek.”

When Arendt came to the campus in 1941, however, it was to meet with a living thinker: Salo Baron, the eminent Jewish historian and the occupant of the first-ever American university chair in Jewish history. An old friend, Baron helped Arendt get published in English. That led to a course she taught in modern Jewish history at Brooklyn College. Baron would also hire Arendt as head of Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, an organization charged with rescuing heirless Jewish books and artifacts stolen by the Nazis. As detailed in a recent Jewish Museum exhibit, the JCN under Arendt helped recover some 1.5 million Jewish books and more than 1,000 Torah scrolls.

The neighborhood must have appealed to Arendt: Although she would go on to teach at numerous institutions, including Notre Dame, UC Berkeley, Princeton and the University of Chicago, New York stayed her home and her lodestar. A few blocks north of Columbia, at 130 Morningside Drive, she and Blucher were finally able, in 1949, to rent their first real apartment, the next stop on the tour. Her guests there included a who’s who of 20th-century writers and thinkers, including the critics Alfred Kazin, Elizabeth Hardwick and Dwight Macdonald; the poets Randall Jarrell, Robert Lowell and W.H. Auden, and the literary power couple Lionel and Diana Trilling.

It was also where she lived when, in 1951, “The Origins of Totalitarianism” was published and cemented her reputation in America.

(The Morningside Drive building has another claim to New York history: In 1961, two years after Arendt left, Columbia tried to evict its residents and those at five nearby buildings as part of an urban renewal project. The tenants at 130, led by the liberal activist Marie Runyon, fought the evictions in a case that wasn’t resolved until 2002. The building was the sole survivor of what became known as the “Forty Years’ War,” and the building’s courtyard is named in Runyon’s honor.)

Arendt’s place at what one writer has called “the contentious center of things” was threatened, however, in 1963 with the publication of “Eichmann in Jerusalem” in The New Yorker. One stop not on the tour, but included in a helpful map from Goethe-Institut, is 108 W. 34th Street. Now a Bank of America, it is the former site of the Diplomat Hotel. There, in the fall of 1963, Irving Howe, Lionel Abel and other members of the New York Intellectuals essentially put Arendt on trial over her coverage of the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem in 1961.

Many felt the now famous phrase she used to describe the Nazis’ genocidal enterprise, “the banality of evil,” minimized Eichmann’s crimes. Arendt’s defenders noted that in calling the Nazi a “completely average man” she hadn’t meant to suggest that he wasn’t evil, but rather, as the critic Adam Kirsch has suggested, to show her “utter contempt for Nazism.”

Worse, and less defensibly, Arendt had shown remarkably little empathy for the Jewish councils and concentration camp prisoners forced and coerced into collaborating with their tormentors. The meeting at the Diplomat was called by Dissent magazine; Arendt didn’t attend, but according to one witness quoted by Hill, every time her name was mentioned, it “was greeted with derisive clapping” (whatever that sounds like).

The controversy around “Eichmann” would dog Arendt for the rest of her life, and threaten to overshadow her other contributions to political philosophy. And Arendt’s reputation took another, posthumous, hit in 1982 when a biographer wrote about her youthful love affair and lasting friendship with her teacher, the famed German philosopher and later Nazi Party member Martin Heidegger. How could a person — a Jew yet — who had written, “Evil comes from a failure to think,” forgive her mentor his complicity in the ultimate evil?

Nevertheless, Arendt remains of the moment. Beginning with the rise of Donald Trump and the resurgence of real and would-be autocrats from Brazil to Hungary to Russia, her works are more popular than ever. Arendt’s literary executor, Jerome Kohn, told Hill that sales of some of Arendt’s works have risen 30-fold in the past few years. In an introduction to a new edition of “The Origins of Totalitarianism,” about the rise of Nazism and Stalinism, Anne Applebaum writes that Arendt in 1951 had analyzed a world that looked eerily like our present one, with “cynical attacks on liberal values,” “the division of the world into warring camps,” a global refugee crisis and new forms of broadcast media “capable of pumping out disinformation and propaganda.”

Hill said Arendt remains both relevant and useful today, not just because of the political upheavals that she lived through and analyzed. “Hannah Arendt is not telling us what to think,” she said. “She is helping us to think. Her work is poetic, and an invitation to think along with her about the loss of freedom, fascism, the rise of evil and what it means to love.”

On the last stop on the tour, at that Upper West Side apartment building with views of Riverside Park and the Hudson River beyond — which Arendt was able to afford after receiving restitution for the income she lost when the Nazis derailed her academic career — Hill painted an indelible portrait of the philosopher lying on her green vinyl sofa, smoking and thinking before heading to her typewriter to put her thoughts down on paper.

Arendt died from a heart attack in 1975, at age 69. After a lifetime of tumult, displacement and controversy, she had found on a quiet street in Manhattan what she described, in a 1974 speech at Columbia University, as a “place of one’s own shielded against the claims of the public.”