Half a century before the Internet was invented, an American Jewish organization was asking how new media might be harnessed in the fight against antisemitism. Their answer, launched in 1937 as the Nazis rose to power in Germany, was a 15-year effort to spread the message of tolerance through comic books, radio, advertising, newsstands and eventually television spots.

The organization was the American Jewish Committee, and its pioneering effort to combat prejudice through mass media is the subject of an exhibit, “Confronting Hate 1937-1952,” which opens July 29 at the New-York Historical Society. The exhibit represents a deep dive into AJC’s holdings by Charlotte Bonelli, AJC’s archives director, and displays the wide variety of materials — radio scripts, cartoons, film clips, posters and magazine and newspaper articles — generated largely under the direction of Richard Rothschild, the advertising executive recruited by AJC to run the campaign.

The materials’ relentlessly upbeat messages about brotherhood and Americanness might strike modern audiences as naive, but at the time the stakes couldn’t have been higher nor the rhetoric more sincere: Hitler was on the march, American isolationists were a political force to be reckoned with, and demagogues such as Father Charles Coughlin and Gerald L. K. Smith were using the airwaves to broadcast popular versions of America-first antisemitism.

Today the AJC has a director for combating antisemitism and maintains a social media presence as well as a podcast, but the emphasis has shifted from actually producing mass media (radio spots featuring their CEO, David Harris, were last aired in 2015), to training policy-makers, media execs and law enforcement about how to recognize, report and root out antisemitism.

I spoke Thursday with Bonelli and Debra Schmidt Bach, curator of decorative arts and special exhibitions at the New-York Historical Society. Our conversation touched on the range of materials created by AJC’s campaign and in what ways, if any, they changed hearts and minds.

Our conversation was edited for length and clarity.

Interview:

Andrew Silow-Carroll: Set the scene: What was happening in America in 1937? In what ways were Jews feeling discrimination and what was the AJC most alarmed about?

Charlotte Bonelli: In the 1930s Jews were facing an unprecedented wave of antisemitism. Naomi Cohen, who wrote the first history of the AJC [in 1972], noted that by 1939, the AJC had estimated there were more than 500 antisemitic organizations operating in the US. Some were certainly receiving propaganda and at times funding from the Nazis. You also have the Depression. You have the confluence of all these things and the nativism hanging over from the 1920s. You have really an explosive mix.

Selma Hirsch, who became the associate executive director here, was the only person alive from the era I was able to speak to. She worked in the Office of War Information during the ’30s and ’40s, and she said that the Nazi propaganda network here was much more extensive than most people ever would have imagined. In AJC polling from 1938, 41% of the respondents answered that Jews had too much power in America. So these views were hardly being limited to an extremist group. They were permeating all groups of society.

Debra Schmidt Bach: Quotas limited the number of immigrants to come in from Eastern Europe, the source of most of the Jewish immigrants coming into the United States. Colleges set quotas for the number of Jewish applicants who could be accepted. Groups like the KKK but also white supremacists, particularly groups affiliated with the Nazis, were active all over the United States. In the exhibition are photographs of the Madison Square Garden rally in 1939, which thousands of people attended. Behind the speakers’ dais is an American flag, a portrait of George Washington and the Nazi flag.

And what is the AJC at this moment? Are they a big, powerful, confident Jewish group? Are they able to get a hearing where it mattered?

Charlotte: The AJC was founded in 1906 in response to the Russian pogroms. Until this point, it had largely focused on diplomacy. They had worked sometimes on legislative efforts, they had supported anti-lynching laws. They had something called a survey committee, which studied the state of antisemitism in America and made grants largely to local organizations to promote better intergroup relations. They realize that they are facing something so serious and so different, that they have to go down a new path, and so they decide that they’re going to enter the world of mass media. This is something very new for AJC. They really have very little experience in this, so they recruit Richard Rothschild, a highly accomplished advertising executive and Yale graduate. He’s just an extraordinary talent.

And he comes on to launch a national campaign that will fight the spread of antisemitism, and eventually it morphs to fight bigotry in general. And they will do so in the mass media world, with comic books and cartoons and posters, newspaper ads and radio programs and just a whole variety of material. And it will aim to reach people through women’s groups, veterans, educational societies and religious groups.

And what was Rothschild’s message?

Charlotte: His strategy is really twofold. One, he is not going to answer antisemitic charges directly. He thinks that’s often counterproductive, and you actually often just spread them. Instead, AJC will introduce the American public to Jews, they will put in positive stories about Jewish contributions to society — to create a whole new reality, so to speak. And he will do it with allies because AJC does not have the logistics to reach millions and millions of Americans.

So we’re really talking about new media — which makes it very relevant today. Talk about some of the finds in the archive and some of the tools the campaign used.

Debra: The Superman comic launched in 1937, and by the time the United States enters into World War II, the armed services are using comic books to teach the troops about things that range from hygiene to how to use new weapons to how to operate vehicles. AJC used comic books, and we have a sampling of them in the exhibition. A number of different titles featured the cooperation between Jews and Christians, and talk about the way Americans can work together to produce unity. Comic books are readable by a range of different literacy levels, and of course, young people were very, very attracted to comic books.

Visitors will also see in the exhibition a sample of radio programs. One is from Uncle Don [Carney], a popular children’s entertainer, who asked children to write essays in 1939 for “Uncle Don’s All Americans Contest” explaining “why it’s grand to be an American.” We’re also going to be showing a movie that the AJC made about the Jewish religious service that was held on the Aachen [Germany] battlefield after that city fell to the Allies. That was a radio broadcast on NBC, and it was groundbreaking in terms of the way it reached around the world.

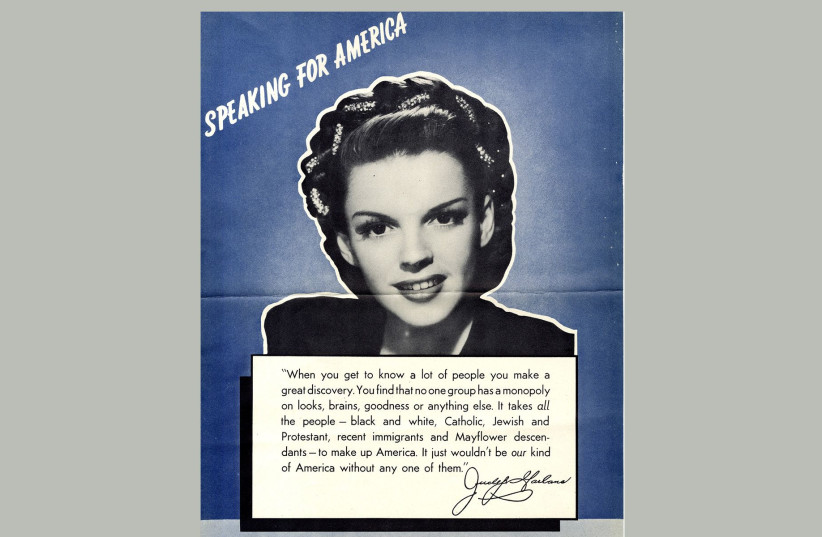

The campaign also enlists pop culture heroes like Judy Garland and Frank Sinatra, and the writer Steven Vincent Benet. How were they recruited?

Charlotte: I think Stephen Vincent Benet might have been recruited through the Writers’ War Board. Milton Krents, who was the director of AJC radio, had no fear about going after big talent. And I would assume that maybe there are connections through the AJC’s lay leadership. I know certainly in terms of comic books, [Jewish philanthropist] George Hecht was one of the owners of True Comics.

Rothchild talks about this in his oral history: The importance of these names is that they would make antisemitism disreputable, and of course they could reach millions. Milton Krents comes up with this idea of “Dear Adolf,” a radio show based on letters from different sectors of American society: farmers, laborers, housewives, immigrants, soldiers. The actors read letters to Hitler basically telling him off and extolling the inevitability of an Allied victory. He got Stephen Vincent Benet to write it, and the actors William Holden, James Cagney and Helen Hayes. The message is that if America is to win this war, we have to stay united and cannot be divided one race against another, or by religion or ethnicity. In one episode Holden says America has the best army and reads the roll call: “DiGennaro, Kelly, Smith, Nathan, Orlando,” and you could not have a stronger contrast with the Nazi Aryan idea of racial purity.

That raises a question. As we move into the war years, clearly what’s happening in Europe is weighing heavily on what’s happening in America. Were there any concerns that a national campaign of this sort led by a Jewish group would be seen as propaganda for entering the war in a way that could be used against them by the isolationists?

Charlotte: That’s a good question. Very often, these projects do not carry the name of the American Jewish Committee. The AJC is basically creating a lot of plums and giving them away. So Milton Krents is loaned out to the Council for Democracy, and “Dear Adolf” is produced under their name with NBC. They also got a spread in Life Magazine, which they were very excited about. There is the concern that if they put a Jewish name on it, it will smack of Jewish self interest, and they want to get the widest distribution possible. It is not until 1943 that the AJC openly sponsors broadcasts and these are done just for Jewish holiday programs, like Purim, and for the battle of the Warsaw Ghetto.

The campaign started as an impulse to fight antisemitism. To what degree was the campaign also about tolerance for other groups?

Charlotte: Almost from the very beginning, there is a recognition that in fighting antisemitism, you will have to fight other bigotries. When Milton Krents writes the scripts for the “All Americans” contest, he has Uncle Don say something like, “Maybe you know a boy or girl who’s a different color than you, or whose mommies and daddies speak a different language than your mommy and daddy or go to a different church. Well isn’t it grand to know that we’re all Americans?”

“Maybe you know a boy or girl who’s a different color than you, or whose mommies and daddies speak a different language than your mommy and daddy or go to a different church. Well isn’t it grand to know that we’re all Americans?”

Uncle Don, All Americans

The cartoonist Eric Godal is a German Jew who fled Nazi Germany, and in his cartoons, you very clearly see that he’s linking these prejudices. So he’ll have Hitler as the Pied Piper and behind Hitler a string of rats labeled with different bigotries: racism, hatred of the foreigner, antisemitism, anti-Catholicism. Young people today may not realize that anti-Catholic prejudice has deep roots in this country.

So I learned a version of Jewish history in which it was the revelations of the Holocaust after the war that shocked Americans out of their antisemitism, or at least drove it underground. And on the flip side, following the war, racist attitudes hardened in the South as well as de facto segregation in the North. So the blunt question I have to ask: Was the campaign successful? Is there a way to measure its actual impact on public attitudes?

Charlotte: Naomi Cohen wrote in her book that she believed that these campaigns were successful in stopping antisemitism from taking firmer and deeper root within this country. That is, you know, her opinion. I think another important element is that they became so good at this, wrapping these messages into an entertaining format, that other agencies come to them for help with their messaging. Within the exhibit, there’s a note from an executive at the Ad Council to Rothschild thanking him, saying that their public service ads wouldn’t have been as good without the input of his team. And Krents wrote something in his correspondence that [before the AJC campaign] it was unheard of to put these human relations messages on the radio.

This exhibit is obviously coming out at a time of increased reporting of antisemitism, and rising concern about hate speech and intolerance. Is that what drew AJC and the Historical Society to stage this at this moment?

Debra: I think it’s relevant for almost every moment, honestly, in my lifetime. I’m hoping this exhibition reignites the conversation about the work that’s left to be done. And we actually started working on this exhibition before the pandemic. I saw this material initially before the pandemic and then it was put aside for a number of months. Looking at it again, after being through the first year and a half of pandemic, it was really a very moving experience. Because the types of messages that were being imparted were really prescient and in a way timeless and ageless.

Charlotte, do you want to add to that?

Charlotte: I think it is a very timely exhibit, but I’ve been interested in this material from the very first time I saw it, which was 20 years ago. It is in some ways inspirational because overall there is an optimistic tone to this campaign. They do believe that these hatreds are so anathema to America that they will, in the end, prevail. They never gave into cynicism.

I also think it shows a willingness to embrace something new. It’s not easy for an organization to go down a totally new path. But AJC did, and I think they deserve great credit for that. And also I think what is relevant today is that they knew that they could not do it on their own, and so they sought allies from many different segments of society.

I read Rothschild’s oral history when he was interviewed in the 1970s, and he was complaining about the malaise in society and that you can’t give into that. He knows that you’re not going to make things perfect, but that doesn’t free you from the responsibility of acting.