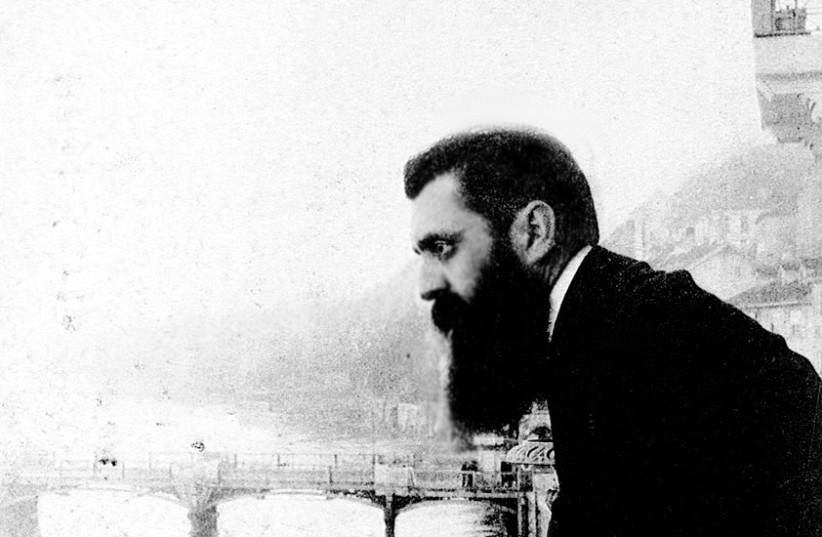

Tormented by a vicious wave of antisemitism, a reporter labors over a book that will solve the Jewish question. The one thing that offers his feverish mind release is an evening visit to the opera. This is one of the key concepts in Theodor, a new Hebrew-language production at the Israeli Opera in Tel Aviv that offers a retelling of the personal struggles of one of Zionism’s greatest champions, Theodor Herzl.

Using the plot device of an older Theodor (Oded Reich) in dialog with his younger self (Noam Heinz), librettist Ido Ricklin and composer Yonatan Cnaan crafted, with conductor Nimrod David Pfeffer, a multi-layered opera that offers a historical perspective to Zionism, as well as a musical one.

Herzl hoped to solve the Jewish question

Faced with the rising tide of hatred unleashed by the 1894 Dreyfus Affair, Herzl labored on a book that he hoped would solve the Jewish question. The only comfort he allowed himself was an evening visit to the opera to enjoy Richard Wagner’s Tannhauser.

The result is Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State). Released two years after the sentencing of the French-Jewish military officer, the book earned the Austrian journalist scorn. It is only in retrospect that the work is seen as a continuation of earlier calls for a Jewish homeland, such as the 1882 work Auto-Emancipation by Leon Pinsker, and its author was awarded the status of a founding father to a country now entering its 76th year.

Wagner was a rabid antisemite, among the first to support the notion that there is a Jewish nation with spiritual qualities that mark it as irredeemably different than that of the German alleged race.

Yet Herzl deeply admired Wagner’s opera and a snippet of it can even be heard in the relevant scene.

This marks Herzl’s personal hardships and entanglements as he sought a solution to the plight of the Jews. Should Jews convert to Christianity en masse, such as Felix Mendelssohn, who was baptized at age seven? Devoting himself to the Jewish nation, Herzl neglected his wife Julie (played by Anat Czarny) and his children.

“Like all operas,” Pfeffer told The Jerusalem Post, “this one was also composed and staged with an eye toward the relative strengths of its performers.”

Czarny, for example, requested to add to her part an element of “Herzl Says.” Used by Israeli children as a variant of “Simon Says,” this addition adds a layer of irony to the opera.

The reality created by Herzl

“AT THIS point in time, we are living six generations after the printing of The Jewish State,” Pfeffer pointed out, “we are living in a reality Herzl created. He is a father figure, the visionary who saw this nation’s possibility, but we are the ones living it.”

“In music,” he continued, “we are moved and even weep due to the combination of words and music, the combination of different frequencies. This is why the opera is a highly abstract art form, the music colors the words and the words in turn affect the music.”

One of the key moments in the opera is when young Herzl (Heinz) wants to be accepted to Albia, a Burschenschaft (student association) for young patriotic German students. To be accepted, one had to prove his valor in a fencing duel. Herzl does it and is accepted, but is later repulsed by the virulent anti-Jewish views expressed by its head, Hermann Bahr (Yair Polishook).

This part of the opera, when Bahr speaks of Jews as the source of all evil, was set to “charming, captivating music,” Pfeffer explained. This was done so that the audience might feel why such views or similar anti-minority views expressed today, can be tempting. “The music is so pretty that one could get a sense of why people would fall for it,” he pointed out.

Cnaan constructed the music for this opera in such a way that it contains references to Chopin and Kurt Weil, for example, but also to early Jewish composers who wanted to create the music of this land, like Sasha Argov, going further to include Aviv Gefen and the rock band Mashina.

“Mozart famously said, ‘My music has something for everybody,’” Pfeffer told the Post. “In this opera, we followed this principle.”

In established operas, like Tannhauser, a conductor approaches the work from within a musical tradition shaped by past performances and recordings. Here, Pfeffer shared, “is a commitment to be the first performance, the standard that will begin this work’s passage in time.”

It also helps that Cnaan and Ricklin can be reached for discussions and feedback as the work nears its completion.

“It is important for me that readers know this is not a protest opera,” he added. “We are inviting the audience to deal with the same reality that Herzl dealt with, and maybe gaze into a mirror that points to where we stand now in relation to his vision.”

“After all,” he pointed out, “people visited the opera during the Dreyfus affair, too. There is always something happening outside the opera house.”

Theodor, sung in Hebrew with English titles, will premiere on Wednesday, May 10, at 7:30 p.m. and will run until Monday, May 15, at 8 p.m. Tickets range from NIS 195 to NIS 445, depending on the seats. The Israeli Opera is at 19 Shaul Hamelech St.

For more information, contact (03) 692-7777. Patrons are invited to Opera Talkback to discuss the opera with the performers after the show ends on Sunday, May 14 and Monday, May 15, as part of their admission ticket.