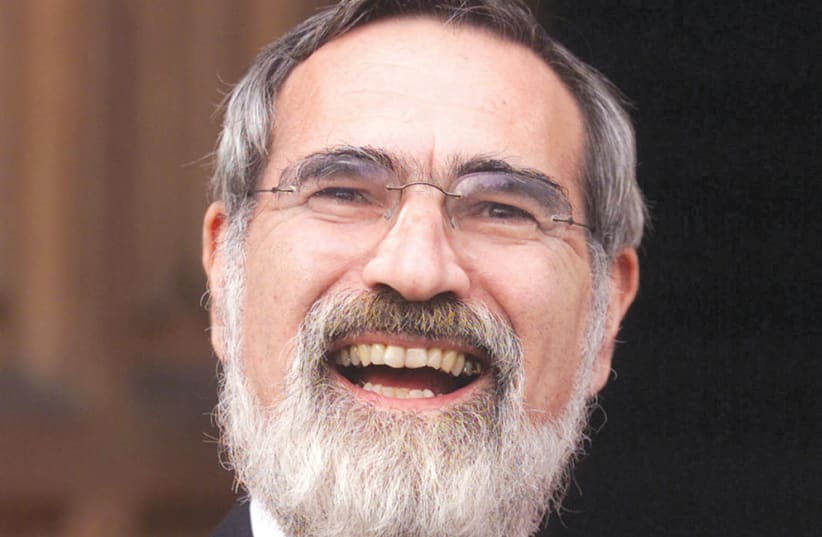

A remarkable man, a truly outstanding figure of our times, has left us. The death of Rabbi Jonathan Sacks ‒ Anglo Jewry’s emeritus chief rabbi ‒ at what is today considered the early age of 72, came as a great and totally unexpected shock to Jewry across the world, but especially to the Anglo-Jewish community in the UK. Chief rabbi for 22 years between 1991 and 2013, in the past seven his already prodigious reputation has been even further enhanced. Not only a towering presence within the Jewish community, he became a well-known and greatly respected personality in Britain generally through his radio and television appearances. He passed away in the early hours of Saturday, November 7, 2020.

Sacks was possessed of a combination of qualities not often found together in one individual ‒ a towering intellect allied to deep human compassion and understanding. He bent his abilities to the service of faith in general and Judaism in particular. Widely perceived as the public face of Judaism in modern society, he was also highly respected in interfaith circles. In 2004, his book The Dignity of Difference ‒ a book he agreed to amend for its second edition to avoid offending ultra-Orthodox opinion ‒ won the Grawemeyer Prize for Religion for its success in defining a framework for interfaith dialogue between people of all faiths and of none. When he was knighted in 2005, the citation read: “for services to the community and to inter-faith relations.” Although widely regarded as the leader of Britain’s Jewish community, as chief rabbi his writ ran only in the UK’s United Synagogue organization, established by Act of Parliament in 1870. He was not recognized as the religious authority in other Anglo-Jewish movements such as the haredi (ultra-Orthodox), Reform, Liberal, Masorti or Sephardi. Nevertheless, with only one or two bumps along the way, he established and maintained excellent relations with all, as he did with the leaders of other faith groups in the UK.

It was this broad and enlightened attitude to religion that gained him the respect of many establishment figures in the UK, including members of the royal family. It was at a royal tribute dinner to mark his stepping down from the Chief Rabbinate in 2013 that Prince Charles described him as “a steadfast friend,” “a valued adviser” and “a light unto this nation.”

Born in London in 1948, Sacks was educated at Christ’s College, Finchley ‒ his local grammar school ‒ and Cambridge university, where he read philosophy. It was while studying at Cambridge that he traveled to New York to meet the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Schneerson, who advised him to seek rabbinic ordination ‒ advice he followed. He gained a double smicha in 1976, one from Yeshivat Etz Chayim, and the other from Jews’ College, London, the seminary which prepares Britain’s rabbis for their ministry.

Sacks’s first rabbinic appointment in 1978 was as rabbi for the Golders Green synagogue in northwest London. In 1983 he moved on to become rabbi of the prestigious Western Marble Arch Synagogue in London’s West End, a position he held until 1990. Between 1984 and 1990, Sacks also served as Principal of Jews’ College. He became chief rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth on September 1, 1991, and in 2009 entered the House of Lords with the title “Baron Sacks, of Aldgate in the City of London.” Asked once whether his chief rabbinate had been too engaged with the outside world, given his frequent media appearances and his interfaith activities, his response was that extra-communal affairs had taken up about 2% of his time. Up to 98% had been spent working within the Jewish community. In support of this contention, he pointed to the vast bulk of his writing.

One great innovation as chief rabbi was his “Covenant and Conversation” website ‒ a concept that would not have been possible for his pre-Internet predecessors in office. Through his website he both published and recorded as videos every week what amounted to a sermon, a perceptive piece of work eagerly awaited and absorbed by thousands in the Anglo-Jewish community. He later gathered these weekly pieces together and published them in several volumes.

Perhaps his greatest and most long-lasting achievement for the community was his work in revising Anglo Jewry’s old-established and long-revered Authorised Daily Prayer Book. Known affectionately as Singer’s after the original English translator (described on the title page in characteristically Anglo-Jewish terms as “the Rev. S. Singer”), it was first published in 1890. It was subsequently reprinted, expanded or re-translated more than 30 times until its final edition appeared in 1992 under the editorship of Sacks.

What followed in 2006 was a totally re-conceived and much enlarged Authorised Daily Prayer Book, incorporating a new translation by Sacks, together with commentary and notes written by him. Preceding the prayers in this new edition is his highly insightful article “Understanding Jewish Prayer”, running to no less than 23 pages.

Anglo-Jewry’s allegiance to the familiar Singer’s was hard to break but eventually, often by way of sets of the new siddurim donated by members of the congregation, UK orthodox synagogues switched over to the new, expanded and more useful Sacks version, which is now standard and likely to remain so into the indefinite future.

Something similar is happening with regard to the mahzorim (prayer books for festivals) for Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur. Israel-based publishers, Koren, have brought out totally new editions, translated by Sacks, in a revolutionary format – namely with the Hebrew on the left-hand page and the English on the right. Koren published two versions of both mahzorim, one for the large US market and the other following “Minhag Anglia” (English custom). The volumes are worth purchasing for Sacks’s introductory essays alone, to say nothing of his acute commentaries, some quite lengthy, which adorn each volume. His preliminary article in the Yom Kippur mahzor runs to 63 pages.

As chief rabbi, Sacks never baulked at ruffling feathers. Well before the spat with haredim over the first edition of Sacks’s prize-winning book, The Dignity of Difference, ultra-Orthodox leaders were incensed in 1996 when he attended a memorial service in honor of the popular Rabbi Hugo Gryn, a Holocaust survivor and Reform rabbi. When his placatory letter to the Haredi leaders, intended as a private communication, was leaked, a storm burst around Sacks’s head.

Another brush with his community occurred two years later, when Sacks agreed to attend a reception to mark the 50th birthday of the Prince of Wales on a Friday evening. Because it was Shabbat, he made the journey from his Marble Arch Synagogue to Buckingham Palace on foot. Even so, community leaders criticized him for not being with his family on Shabbat. Sacks insisted that it was an established protocol for chief rabbis to accept direct royal invitations, and that an exception should be made for the “expression of Jewish loyalty to the country and its head of state.” This proved to be a passing storm, soon forgotten as Sacks’s solid achievements in terms of the expansion of education and the rationalization of Jewish social care became manifest.

Sacks was once asked what the toughest moment had been when chief rabbi. His reply was far from what most in the Jewish community would have anticipated.

“There is no question,” he said, “that the toughest moment actually came in 2002 with Jenin.” In the midst of the Second Intifada, the UK media was suddenly flooded with lurid tales of an Israeli massacre of 5,000 civilians in the Jenin refugee camp in the West Bank, accompanied by horrific and deliberate war crimes. Based on the uncorroborated statement of one individual, the incident at Jenin had been blown out of all proportion, and the UK media seemed to be doing their best to stoke the flames. “I had to make a calculated decision,” said Sacks. “I’m not the Israeli ambassador, but is this just too serious to leave?” So he went on the BBC’s prestigious Today program – sometimes described as the jewel in the crown of BBC radio ‒ and predicted confidently that when the full facts emerged, the death toll would be nothing like the figure widely claimed. Four days later at a rally in London’s Trafalgar Square, the facts became known for the first time – the Jenin battle had indeed been fierce and bloody, but it had resulted in 52 Palestinian deaths, together with 23 Israeli soldiers. Sacks had known the truth, even before the BBC, because his staff had called Israeli soldiers in Jenin and learned it from them.

How to summarize the achievements of a man so erudite, so prolific, so open-minded, so revered in his own country and across the world? He was showered with honors – 26 of them; delivered some 60 major courses of lectures; was awarded 14 prizes and authored more than 30 books. Throughout, his focus was on scholarship, on probing for the truth in Judaism and disseminating it, and on understanding the beliefs of others.

Sacks was once asked about his major achievements as chief rabbi. He singled out the fact that he persuaded community leaders of his orthodox organization to permit women to become chairpersons of synagogues. When he took office “there were no women on synagogue boards, there were no women, except in observer status, on the United Synagogue council. We had to make that a gradual change, and I’m glad that within my term of office women were able to become chair people.” On leaving office Sacks made it clear that, far from slowing down, he intended to expand his activities. He would be going in “the same direction but in a global way – writing, teaching, broadcasting and speaking on a more global forum. There’s a hunger around the world for the message that we’ve been delivering of a Judaism that engages the world. So more teaching, more writing and seeing the possibilities of the web.” That is the story of the final seven years of his life.