If you’ve ever grabbed a handrail in Jerusalem’s Old City or navigated the Knesset with someone disabled, you have engaged with SHEKEL-Inclusion for People with Disabilities, a Jerusalem-based organization. SHEKEL provides an astonishing, and growing, set of services for people with intellectual as well as physical disabilities throughout Israel.

But SHEKEL’S goal is broader than the myriad of services they provide. “SHEKEL seeks to give each person with disabilities a very real opportunity to fulfill their personal potential and individual aspirations,” says CEO Clara Feldman. Equally important, “SHEKEL seeks to make people with disabilities welcomed and wanted citizens of society.”

“SHEKEL seeks to make people with disabilities welcomed and wanted citizens of society.”

Clara Feldman

That message is succeeding: “In the last few years, the population in Israel are more ready to see people with disabilities included in daily life,” says Feldman. “Everyone has the right to live in society and everyone has dreams.”

Feldman notes that 12% of the Israeli population has a disability of some kind, which should make inclusion a matter of course and not something out of the ordinary.

Begun jointly in 1979 by the Labor and Social Affairs Ministry, Joint Israel, and the Jerusalem Municipality, about 600 employees and 700 volunteers today assist about 8,000 Jews, Muslims and Christians, both religious and secular, with a range of disabilities that include intellectual, physical and sensory. Branches have expanded beyond Jerusalem to many cities within Israel.

SHEKEL’s main areas of activity include housing in the community and independent living for people with disabilities, vocational training and employment, therapeutic services, programs for children and youth, accessibility, and culture and leisure activities.

The goal is to provide inclusion in all areas of life, including cultural and leisure activities such as game nights and even – until corona made them more local – trips abroad for adults living in SHEKEL housing. “We all want to go on vacation and experience other cultures, so while it’s an undertaking to plan such trips, it’s an undertaking of love,” says Feldman.

Innovation is the rule.

SHEKEL has had iterations of restaurants at its Jerusalem headquarters; one that recently opened serves kosher Greek food and has musical Taverna nights. The restaurants have been a haven for neighbors in the community and a training ground for young adults with disabilities. The training runs well beyond serving, clearing, and cooking, all skills several of the graduates now use in other restaurants. Coming to work means needing a Rav Kav (travel pass) and a bus schedule, and a visitor to the restaurant one Friday watched as servers finished their shifts and proudly planned their routes home – a hallmark of many of the work programs run by SHEKEL.

“I feel proud I can do it on my own,” says a young server. Fostering independence has prepared many to find jobs, hobbies, and friendships, creating, as Feldman says, the lives we all yearn for.

In a fourth-floor practice room at the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance, Idan Zvulun, 37, bends low over his guitar, concentrating on the chords of the country music song by John Denver, “Take Me Home, Country Roads.”

“I love playing and learning new songs,” Zvulun says enthusiastically. “The (Music) Academy has exposed me to new genres. I used to only play Mizrahi [Middle East] music but now I’ve been exposed to pop and even music in English.”

Zvulun is a member of a special orchestra called the Israel Integrative Orchestra, which is a collaboration between 20 adults at SHEKEL and 20 students at the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance. The students at the Academy are paired up with SHEKEL adults and receive a Perach scholarship for their time. The orchestra was founded three years ago, in collaboration with the Yitzhak Navon community unit of the Jerusalem Academy, and conductor Ido Marco says it is a rewarding, if challenging, enterprise.

“Interpersonal relations can be a challenge, and every rehearsal we have different situations we need to deal with,” Marco says. “The orchestra combines players with different musical levels, and we try to make them all sound their best.”

At the same time, the orchestra also creates a special feeling.

“Music can make people come together and create something new,” he says. “It’s a universal language and allows them to speak together. We basically connect people.”

The music students say they learn as much from their counterparts in SHEKEL as they hope to teach them.

“I’ve been part of this project since it started, and it’s been a very moving experience,” says Shalev Ron, a contrabass player who covers his dreadlocks with a knitted beret. “We are creating something that is really equal. We are creating something new together that’s really all of ours.”

For some of the SHEKEL players, the orchestra is a chance to express themselves in a different way.

“I’ve been playing violin since I was six years old,” says Sima Kogan. “Here we all accept each other.”

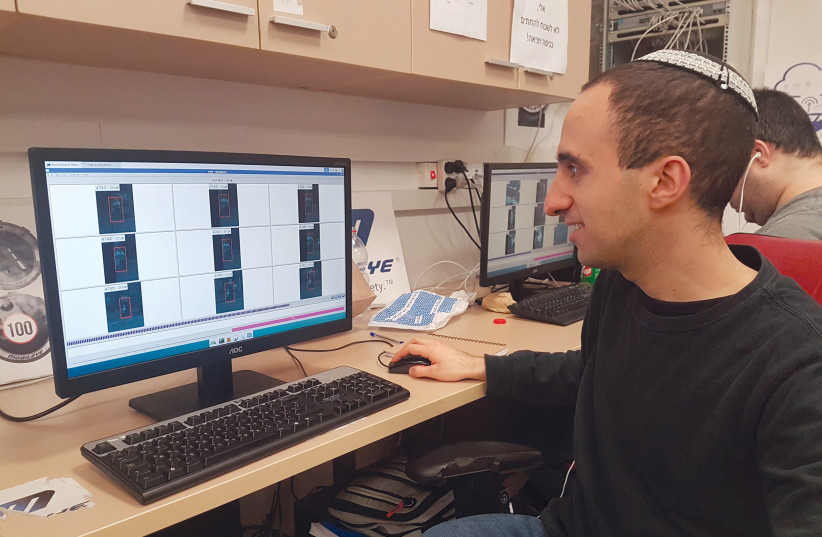

Another SHEKEL project takes place in collaboration with the hi-tech company Mobileye, now owned by Intel. Every day, 13 young adults on the autism spectrum come to the Mobileye offices where they work in data tagging of the world’s roads, in preparation for Mobileye’s driverless cars.

“Their tasks are entirely on the computer, using Mobileye programs to detect specific objects or scenarios,” says Mollie Goldstein, the SHEKEL counselor at Mobileye. “The work requires focus, attention to detail and understanding instructions.”

The workers from SHEKEL take great pride in doing their job well.

“I feel like I’m making roads around the world as safe as possible and it’s a great honor to feel like I’m helping to save lives,” says Jonathan Trauner. “I’m usually the first of my team to arrive in the morning and the last to leave. I always try to give 100%.”

Trauner recently celebrated his 28th birthday and was touched by the cake that his manager brought for him. He says it is sometimes difficult to overcome his “social communication challenge” at work, but feels he is succeeding.

Eli Schreiber says he used to struggle to get to work on time and to stay motivated during the workday, although that has gotten better with time. He says that he enjoys the job and likes the salary, and he hopes he is educating his colleagues about people with disabilities. The salaries for the SHEKEL time are on the same scale as other workers with similar skills who work at Mobileye.

“I hope I’m changing attitudes and that more companies will be willing to hire people with autism,” he says.

Like the orchestra and road tagging, most of SHEKEL’s programs are one of a kind. Five days a week, for example, the “Open Space” farm on Moshav Kfar Shmuel gives young adults with low-functioning autism the chance to connect with the world around them by working and interacting with animals, nature and visitors to the horse ranch and farm. Parents of participants say the interaction with the animals – who are neither judgmental nor critical – has allowed many of the young adults to more fully engage with people as well. SHEKEL has now opened similar programs on Kibbutz Ramat Rachel in Jerusalem, and Ganei HaTeva and Merkaz Shira at Rupin College, both in Tel Aviv.

On a walk through the Old City of Jerusalem, Dr. Avi Ramot, director of SHEKEL’s Israel’s Accessibility Center, stops to tell a family struggling to lift their mother in a wheelchair up some steps that if they take a very slight detour, they will come to a ramp, made of stone that exactly matches the millennia-old rock of the area, that will make it much easier for them to navigate the incline.

Ramot should know. For several years he led the accessibility project of the Old City, which has made much of the area accessible for anyone. “It is a city for all, so we made it easier for people with disabilities to live and visit here,” says Ramot.

The work, which took over a dozen years and was paid for by several ministries, required many changes including paving, installation of ramps, and inclines and handrails for the narrowest sections. Using a phone app – Accessible JLM-Old City – brought in by SHEKEL, anyone visiting the Old City can design an accessible route.

SHEKEL also led the accessibility upgrade to the Knesset building, completed a few years ago, including straightening out its once curved floor. The building is now one of the most accessible parliaments in the world. One cool accessibility feature that showcases opportunities for independence for people with disabilities is the Wayfinding Station, which lets a user with visual impairment, relying on a phone app, hear descriptions of the surroundings, allowing them to walk around unaided. The app lets them call for help if needed.

But accessibility doesn’t stop at access. Through a partnership with SHEKEL the Knesset employs ten full-time staff members with intellectual disabilities who work as technology and secretarial aides. A SHEKEL staff member is on hand to support the employees. A SHEKEL Knesset employee working as an office assistant tells a visitor, “Every day I come to the Knesset, and I tell my friends where I work. Sometimes they don’t believe me, but it’s true!”

Newer projects include a partnership with HaMetzion, a network of vintage and secondhand stores where SHEKEL participants are trained in different aspects of retail. And if you go to many weddings and bar or bat mitzvahs in Israel, you’re likely to see invitations designed by SHEKEL’s graphic design studio, which like many other SHEKEL programs pairs differently abled participants with peers.

Other SHEKEL employees make candles and hand-sewn toys during a full workday that are sold at the popular SHEKEL gift shop at its Talpiot headquarters. Told by a visitor that the candle he is making looks just like the one she purchased at the shop and is excited to use at home, the SHEKEL craft artist beams with understandable pride.

“Each project we support and add has a single focus,” says SHEKEL president Lihi Lapid, a journalist and the wife of Foreign Minister Yair Lapid. “The organization’s vision is to develop opportunities for every person with a disability to live their lives as an integral and valued part of the community.” ■