Liraz Charhi, star of the smash hit TV series Tehran, is more than just a pretty face. Make no mistake: she’s also a very pretty face, with a lithe, slender physique. Oh, and she can also sing. She composes haunting, evocative melodies for the Persian lyrics that she writes herself, and performs all over the world. But, in this crazy world of changes and more-of-the-same, she is fast becoming a force for freedom and a lyrical voice of hope.

Charhi was born 44 years ago in Ramle, central Israel, to parents who had recently emigrated from Iran.

“Although I lived in Israel, I kind of grew up in Tehran,” she recalls. “We ate gormetsabi and gondi for dinner, threw glasses of water at taxis before trips for good luck, and carried salt in our pockets to spread on heads of loved ones so they should succeed.” Along with the meat stews redolent with green herbs and dry Iranian lemon served on rice and potatoes, she imbibed great respect for her elders, family togetherness, and a second mother tongue.

Abiding by your father’s rules can be a challenge when, at age six, a little girl starts living her dream – performing and singing on stage – against all patriarchal principles. “In Iran, women were not encouraged to sing,” explains Charhi, whose grandmother had a beautiful voice. (Blessed vocal chords, it appears, abound in the family; Rita, the iconic Israeli singer, is her beloved aunt.) Wives were supposed to work and raise kids. Even in democratic Iran, artists were often considered on the cusp of being prostitutes. Today, her father, Moti, is her biggest fan, but in the early years Charhi had to sneak out of her home in Herzliya to sing in a choir and work to pay for her own singing and acting lessons.

In the meantime, her parents were filling her head with an idealized picture of life in the old country: sleeping on rooftops in the summer, eating the sweetest ever watermelons, vacationing by a blue sea. The soundtrack to this idyll was kitsch, sugary music from home – wedding songs, cheerful dance numbers, frothy tunes. Tired of constantly switching identities, Charhi stopped hiding her meatloaf sandwiches from her friends and adopted a cream cheese and cucumber regime, choosing to be an Israeli through and through.

Blessed with beauty, presence, talent and a wonderful voice, little Charhi grew up to shine in movies such as Turn Left at the End of the World; Fair Game (with Sean Penn and Naomi Watts); and A Lead Quartet (starring Seymour Hoffman). She released two albums, acted in television series, starred in Israel’s National Theater, and very quickly built a successful mainstream career in Israel and abroad.

Yet, she says, the “hole in my heart” just didn’t close. None of this success seemed too meaningful to her; she didn’t feel connected to her essence. Then, on a work visit to Los Angeles, she reluctantly went to visit some cousins she hadn’t met before, and fell in love. In “Tehran-geles,” with the city’s huge Iranian population, her heart began to heal.

“I scoured vinyl record shops for recordings of Iranian women singers, and through my bond with them I started to write my own music, driven by rage and the urge for freedom.”

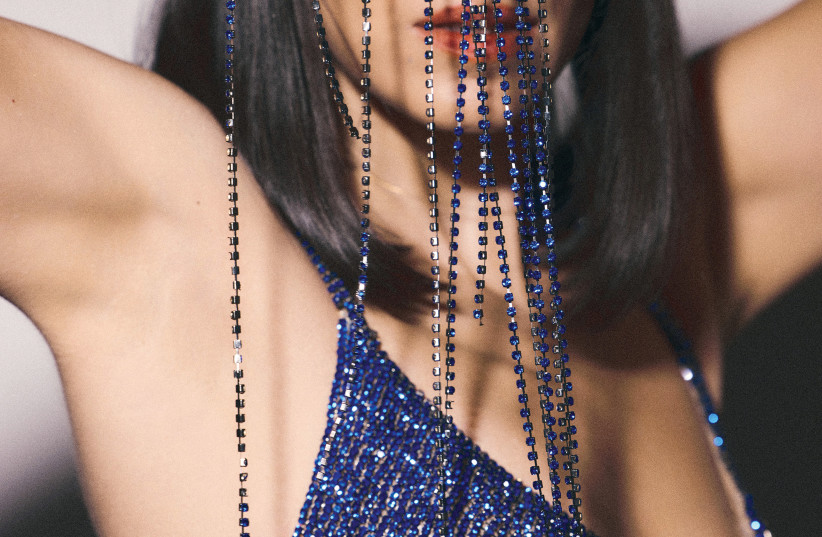

Liraz Charhi

“I scoured vinyl record shops for recordings of Iranian women singers, and through my bond with them I started to write my own music, driven by rage and the urge for freedom,” she recounts. “After the Iranian Revolution, when women were definitively forbidden to sing in pubic or go on stage, I realized that my music was more than just me – I was closing a circle and singing for the women in a country I have always longed for.”

Charhi informed her team that she was going to focus exclusively on singing in Persian. Her first album was a collection of covers of Iranian women’s standards. Her second and third albums – music and lyrics written and composed by her – were dedicated to the muted women in Iran. Astonishingly, after her first record became a worldwide hit, also in Iran, women artists (and a few men) began reaching out to her clandestinely, often using fake identities or switching social media accounts.

Female artists in Iran fear for their safety

In Iran, where it is forbidden to even listen to women’s singing in a car, female artists fear for their safety. However, Charhi was compelled by the stories of those who contacted her, and gradually she began incorporating their smuggled music and lyrics into her own. Eventually, she hired a local producer with an underground studio in Tehran for Skype sessions with her new collaborators … In a scene fit for a Netflix drama, only the back of the producer was ever visible, and the blurred images of the musicians.

“It was totally unreal,” says Charhi, who is always aware of how life-threatening cutting an album can be in Iran. “And I was filming Tehran at the same time. Totally crazy.”

One crazy step followed another: The next was a studio session for a unique collaboration with a few Iranian artists, in person, in Istanbul. She doesn’t provide details, but the logistics and security obstacles were enormous. “Zan Bezan,” the first song on the album which came out of the collaboration, means “sing, woman.” But the phrase has a second meaning – “Yalla! Go for it!” Charhi composed the song when she was eight months pregnant with her second daughter, vowing to meet the challenges of parenting, performing, touring, creating and still having the energy to say hello to her actor husband, Tom Avni, from time to time. The song, with its undertones of empowerment, became the soundtrack to the Iranian “hijab revolution.” Women posted videos of themselves on social media ripping off their veils to the beat.

Charhi herself delivers a powerful virtual punch as she performs the video clip with back-up dancers who all join her in ripping off the sinuous veils that initially hide their faces and hair.

Last October, she released Roya, the album that was secretly recorded in Istanbul. The dream/fantasy/vision theme song extols building relationships between Israelis and Iranians while fearing for the latter’s safety. The good energy of the music and the plea to rejoice resonated in Tehran. Suddenly, around the world audiences at her stage shows arrived with Iranian flags, protesting the oppression of the mullahs and the military. At a special concert in Krakow, Iranian singers, swathed in glowing golden veils which they could not remove for security reasons, danced and sang with Charhi in a transient, transcendent moment of almost-freedom.

“My music has morphed from niche to world music,” says the performer, who sings in Persian from Israel to women who are technically almost at war with us. And in this insanely changing world, she wonders whether things will reverse one day. Already, she says, public shows have been canceled by the new Israeli government, reluctant to have a woman’s voice heard by men.

“This isn’t so unexpected,” she adds, remembering that as a member of the Army Entertainment Band, she was asked not to swing her hips when she sang in front of the IDF troops.

Who knows – is it possible that one day Charhi will be singing protest songs of freedom in Hebrew from a free Iran as women in Israel struggle to throw off their imposed sheitels and scarves? Nothing seems too far-fetched anymore.

Zan bezan, sing women! Here’s to keeping our voices, and our heads, out there. ■