One of the joys of being a journalist is either being sent abroad to travel, or receiving an all-expenses-paid invitation to travel. Of all my trips abroad, the countries where I have visited most frequently are Poland, where I have been at least eight times, and Austria, where I recently made my fourth visit – this time at the invitation of the European Jewish Congress.

All dozen or so trips were either directly or indirectly related to the Holocaust. It’s something difficult for Jews to avoid when traveling through Europe, especially if family members were among the murdered or among the survivors who told their stories. In my family, there were relatives on both my mother’s and my father’s side who were murdered in Auschwitz and Treblinka, and both had surviving cousins. My mother also had a sister who survived a tortuous forced labor camp, and both my mother’s sisters were married to Holocaust survivors. So the Holocaust was something with which I had grown up from my earliest memory, and continues to occupy a place in my consciousness.

My first visit to Austria was at my own expense in the course of making aliyah in 1973. Coming from Australia, and in less than comfortable financial circumstances, I wanted to make the most of my long journey, because I doubted that I would ever have enough money to leave Israel once I got there.

In those days, one could visit any country on the route of the airline, at no extra cost, so long as one did not change direction, and kept traveling in more or less a straight line. Austria was included in my stops and deliberately so, because one of my great missions in life was to interview Simon Wiesenthal. Coming from a country that was free and open, where accessibility was seldom a problem, I was amazed that I had to go through a security check in order to meet with him. It had never occurred to me how careful a professional Nazi-hunter has to be to protect his safety.

When I called the telephone information service to get Wiesenthal’s phone number, the operator told me that she was not at liberty to divulge it. She inquired why I wanted to speak to him, sought several details about me, and asked where I could be reached. She then instructed me to remain near the phone for the next 15 minutes.

It took less than that for her to call back to say that Wiesenthal was willing to see me. She gave me the address, and I sped there, as if on eagle’s wings.

He was a hulk of a man, sitting in a small cramped office, his desk piled with newspapers and magazine, as were the bookcases lining the walls. He was very forthcoming and easy to interview. Before leaving, I told him that I had read of Russian Jews who had been permitted to leave the USSR and had reached Israel, but could not adapt to life there and were returning to Russia. Did he know anything about them? He did and told me where to find them.

Austrian Chancellor Bruno Kreisky, though opposed to Israel’s policy vis-à-vis the Palestinians, allowed Austria to be a transit point for Soviet citizens leaving the USSR for the West. They also used Austria as a transit point for their return.

Among the Russians whom I found was an engineer who spoke fluent English. He had stayed for many months at the absorption center in Jerusalem, which was to be my destination in Israel. He had wanted to leave, find a job and start a new life. That might have been possible if he didn’t speak English. But the global Let My People Go campaign was going strong, and it was in the interests of Israel to have someone from the USSR who could answer the questions of visiting groups of activists from UJA, UIA and numerous other organizations, so the people from the Jewish Agency kept him in the absorption center. He felt like a monkey in a zoo, and that was never one of his ambitions. The only solution was to go home. That was easier said than done, because Jews leaving the Soviet Union had to forfeit their citizenship, which rendered their passports invalid.

My second visit in 1982 was as a member of the Israeli delegation attending an international conference of women journalists in Budapest.

Hungary was still Communist at the time, and there was no airline connection between Israel and Hungary. To get there, we had to go to Austria, where we stayed overnight, and then take a plane to Budapest the next day. On the return leg, the travel agent had neglected to make hotel reservations for us, and it was impossible to get a hotel room for love or money because Austria was teeming with international conferences.

Most of our group either changed flights or simply spent several hours at the airport. At that time The Jerusalem Post had a regular women’s section with its own editor, the late Helen Rossi, who was one of the most veteran members of the editorial staff. Already in her seventies and in poor health, she was reluctant to be caught up in the rush, and wanted to stay in Vienna overnight. I explained to her that if I could find accommodation, we would have to stay over Shabbat because there was no flight to Israel on Friday. That was fine with her. But it was my task to find lodgings.

I remembered reading about a hassidic movement that maintained apartments for their own people coming in from abroad, as well as for Russian Jews passing through on their way to Israel. I have no recollection of how I found them, but once I made contact, they were very obliging. They refused to take payment, but insisted that we eat only the food that was in the two-bedroom apartment, and not bring in any other food – especially meat.

They also requested that there be no major violation of the Sabbath – namely no smoking or turning lights on or off. For me, that was no problem, but for Helen, who was a chain smoker, it was a very tall order. There was no danger of her going out to buy food, because she could barely walk, and had to hang on to me once we were outside. But not smoking for 24 hours – that was tough.

On Saturday morning, there was no sound from her room when I got up, so I went to synagogue services without disturbing her, and after services went for a walk in the nearby park. Her door was still closed when I returned to the apartment, and thinking that she may want privacy, I did not disturb her. But after nightfall, when her door still remained shut, I began to worry.

I knocked, she opened the door, and it was like walking into an inferno. She had been smoking one cigarette after another for the whole time that the door was closed. The room was filled with smoke and the acrid odor of tobacco. There was no point in getting angry with her for causing my promise to be worthless. It wouldn’t clear the smoke, and it wouldn’t relieve the smell. My only hope was that as we were leaving the following afternoon, no one could come to clean the apartment until the following morning, by which time the smoke and the stench would have evaporated.

The third time I went to Austria it was to write a story about Obertauern, 90 kilometers south of Salzberg, and which during the summer, when there are few tourists in the alps, becomes a ghost town.

Some enterprising haredi tourist operators had taken over the recently constructed Cinderella Hotel, made it completely kosher, and had brought mainly haredi vacationers from Israel, plus a few from America and England. The hotel and several others in the area belong to Hans and Heli Gruber, who work closely with Reinhard Oberholzner, a business consultant who has many important contacts in Israel’s tourism industry. All three believe that if they build a hotel that is strictly for haredi Jews and includes amenities such as separate meat and dairy kitchens, a mikveh (ritual bath) and a synagogue, they can do big business.

Interestingly, Oberholzner, who loves Israel, and gets along famously with Jews – even to the extent of donning a kippah, going to Friday night synagogue services, and then joining Jewish friends for a traditional Friday night dinner – is the grandson of two high-ranking Nazi officers. He insists that helping Jews do business tourist-wise in Austria is not related to penance, but something he simply enjoys doing.

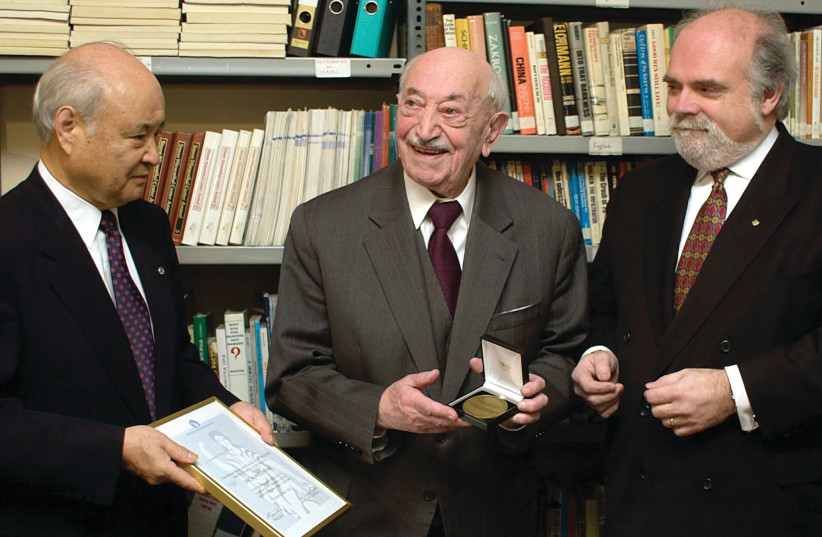

The reason for my most recent visit this month was two-fold: one was to attend the unveiling of the Wall of Names listing 65,440 Austrian Jews murdered by the Nazis, and the other was to listen to EJC President Moshe Kantor outline his vision for fighting antisemitism and preserving the memory of the Holocaust.

Kantor believes that there must be a change in the language used to impart information to today’s youth.

It must contain the idioms that they use today and not the language of yesterday, which as far as they’re concerned is largely ineffective. Education against all forms of racism must begin at the earliest possible age, he says, and that to make the concept of antiracism and respect for all people attractive to the young, “we have to learn their language.” When it is put to him that what children learn at home in their formative years tends to stay with them, Kantor’s retort is: “Social media is more influential than family education.”

Well aware that social media is equally powerful for good and for bad, Kantor wants to use star power – namely entertainers and athletes who are the icons of the current generation of youth – to put out the message of tolerance, respect and equality on every social media platform.

I doubt that I’ll be making a fifth trip to Austria, but if I do, I hope it’s as a tourist.