Art and culture in Jerusalem: Celebrating diversity over divisiveness

In Jerusalem, art has a crucial role to play in creating a city that embraces pluralism and fights intolerance

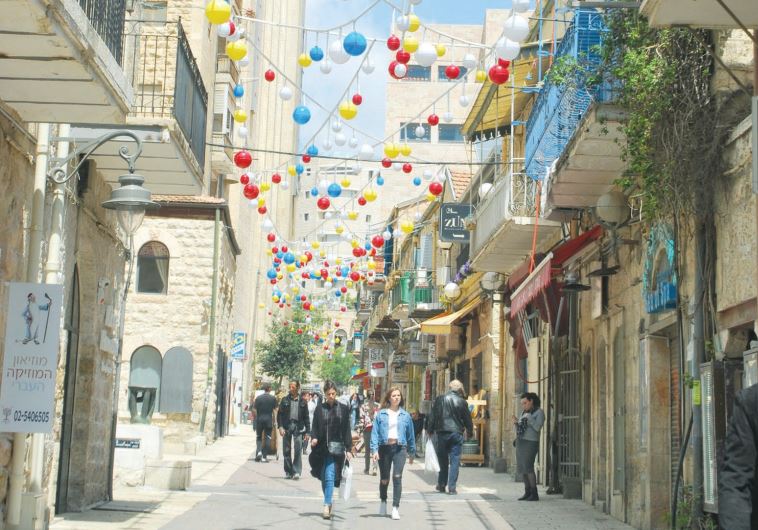

'Street art' on Yoel Moshe Salomon Street in the center of Jerusalem(photo credit: MEITAL SHARABI)Updated:

'Street art' on Yoel Moshe Salomon Street in the center of Jerusalem(photo credit: MEITAL SHARABI)Updated: