Ester Wasserstrom was eight years old when World War II broke out. She spent the war in hiding in the forest, traveling between Ukraine and Poland. While she was never in a concentration camp, she lost her entire family during the Holocaust.

“As a child I was very closed, very quiet,” she says, sadly, in an interview with The Jerusalem Report in her Ramat Aviv home. “I had no mother, no father, nobody to guide me or to worry about me. Everyone took care of themselves first.”

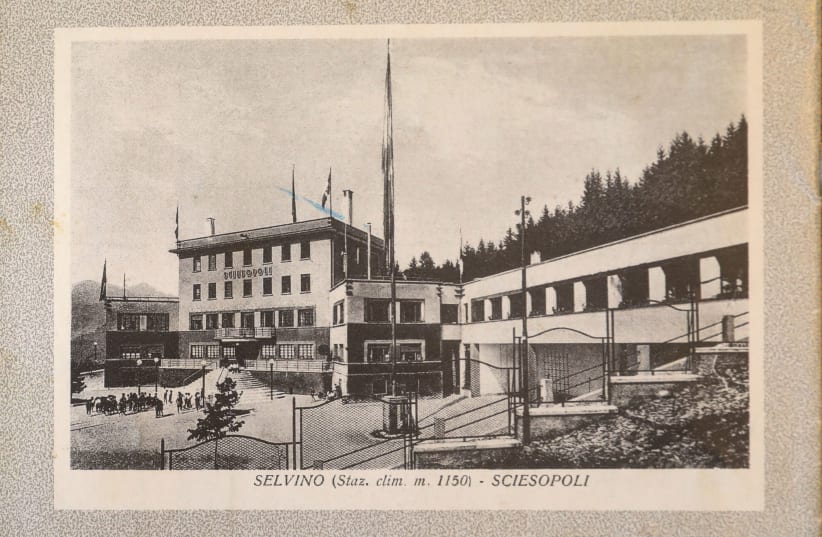

The end of the war found her in Lodz, in Poland. The Zionist movement, Aliyat Hanoar (Youth Aliyah), arranged for orphans from all over Europe to travel to Selvino, a small town in northern Italy about half an hour from Bergamo. It was a long trip, she remembers, in a truck over the mountains. There, more than 800 orphans lived in a compound called Sciesopoli, which was formerly used to house the children of Fascist officers under Benito Mussolini.

“There were 30 cots set up in a large hall for us, but just having a bed with sheets was such a luxury,” Ester says. “At the beginning, there wasn’t enough food, and the soldiers there [from the Jewish Brigade] didn’t have any idea how to deal with children. We always asked for more food. There in Selvino we learned some Hebrew and a little about Israel. We also worked in the kitchen and with the younger children.”

She says many of the children there used to hide food in their pockets, afraid there would not be any more the next day. The counselors from the Zionist movements established a schedule. Every day there was a flag-raising ceremony followed by calisthenics. There were classes in Hebrew and in Zionism. The children were taught about kibbutz life in Israel and told they too would help build a kibbutz, which they eventually did – Kibbutz Tze’elim in the Negev.

The house was run by Moshe Zeiri, a Jewish Zionist who was part of the Jewish Brigade in the British Army. In 1946, he came to Selvino to run Sciasopoli. His daughter, Nitza Sarner, who lives in London today, was almost five years old when she and her mother traveled from Palestine to Italy to join him.

“That winter was one of the coldest that many people remembered, but we were warm in the house and we went on many hikes,” Sarner says. “The whole house used to celebrate all of the festivals and, of course, Shabbat. There were plays for Hanukkah, dressing up for Purim, and a big Seder with dances, readings and singing.”

When she arrived in Selvino, Sarner says, she spoke only Hebrew, but she soon learned Yiddish to communicate with the children there. Italians from the town volunteered in the house as well.

Ester remembers that the town of Selvino was beautiful, surrounded by snow-covered mountains. The Jewish orphans had little contact with the local Italians, she says, but there was a photography studio in town, and they often went to take photographs. She still has some of those photos in her immaculate two-bedroom apartment all these years later.

She lived in Selvino for about eight months, and then it came time to leave for Mandatory Palestine. At that time, in 1947, it was under the control of the British Mandate, which prevented many Jews from entering the country.

By this time, Ester was 16, and she remembers that she and the others traveled the length of Italy to reach the southern port of Metaponto. There, they boarded a ship called the Haim Arlosoroff, which originated in Sweden and had already taken on 684 Holocaust survivors, including many young women who had survived the camps. One of those women named Malka, a survivor of Bergen-Belsen, would later give birth to Benny Gantz, who currently serves as Israel’s alternate prime minister and defense minister.

There were a total of 1,384 immigrants on board. The captain of the ship was the famed Aryeh “Lova” Eliav, and Ester remembers the journey as being difficult.

“We slept on the deck and whenever we heard a noise we had to lay down and cover ourselves so the British wouldn’t discover us,” she says.

Unfortunately, the ship was discovered by a British spy plane and a battle broke out between the British forces and the young men on board. The ship approached Haifa Bay, but landed opposite a large British base and everyone was deported to Cyprus.

One day in Cyprus, she says, a neighboring DP camp had an exhibition and she walked over. A young woman ran up to her, and it was her cousin. This cousin, who made aliyah just a few years later, later tragically committed suicide.

Once the State of Israel was declared in 1948, Ester was able to reach Israel and was drafted into the first Nahal Brigade. She became one of the founders of Kibbutz Tze’elim. It was there that she met her future husband, Mordechai Wasserstrom, who had come on aliyah with the Tehran Children, a group of Polish Jewish children who escaped the Nazi German occupation of Poland, found refuge in orphanages in the Soviet Union and then evacuated with several hundred adults to Tehran before finally reaching Mandatory Palestine in 1943. They married and moved to Ramat Aviv, in the apartment where she has lived since 1958. She has lived a good life working in the textile industry, cutting materials and raising three children, seven grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

The “Children of Selvino,” as they became known, stayed in close touch over the years. “They were my family,” she says. “Now many of them have died, but we were in touch for many years. I didn’t have a father or a mother, but I had them.”

Her son, Avi Wasserstrom, remembers celebrating many events with other Children of Selvino families. A few years ago, Ester took her entire family to visit Selvino on a trip organized by Miriam Bisk, chairperson of the Children of Selvino. Bisk’s parents were counselors in Sciasopoli, teaching the children how to prepare for life in Israel. She herself was born in a DP camp in Cyprus in 1949.

“It was a kind of pilgrimage,” Bisk says in a Zoom interview from her home in New York. She says they met with the mayor of the town and took the second and third generation of the Children of Selvino all over the village including of course, their former home in Sciasopoli.

Another gathering was set for May of this year but was canceled because of the coronavirus pandemic. Selvino is quite close to Bergamo, which was the center of the pandemic in its early days. Bisk decided to fundraise among the Children of Selvino to help the local hospital there.

“When the children were living in Selvino, if they needed to go to a hospital, they went to Bergamo,” Bisk says. “I really wanted to do something to help them. At first I wasn’t sure we would get more than a thousand dollars. But we raised more than nine thousand dollars, and it was the most uplifting feeling. We got beautiful letters from the mayor and there was a lot of articles in the press in Italy.”

TODAY, MANY of the original Children of Selvino have died, but their children and grandchildren still feel strong ties to the town. Their connections have even expanded to Italians who live in the area.

Anna Sternfeld is an Italian Jew from Milan who has a summer home in Selvino, and is one of the founders of the Italian branch of the Children of Selvino. Sternfeld says she had always been curious about the large complex of Sciascopoli, which today is in bad shape. She started asking around and uncovered the story of the Children of Selvino.

She found others, including several non-Jews, who are interested in spreading the story of the Children of Selvino to Italian children. They make frequent presentations in local schools, bringing a traveling exhibition which includes photographs and archival material.

“Our mission is to advocate for social justice against prejudice and racism,” says Bisk. “We teach them about the Fascist movement and open a discussion about racism and antisemitism in Italy today.”

Anna Sternfeld says she is proud of their recent move to help the hospital in Bergamo.

“As an Italian Jew I am very proud of what has been done,” Sternfeld says. “I think it is a great gesture of human solidarity towards a population that many years earlier had welcomed and restored the lives of many children who survived the horrors of Nazi fascism.”

Back in Ramat Aviv, Avi Wasserstrom says he has donated as well.

“The Italians may have done it because they felt guilty about supporting fascism in the Second World War,“ he says, sitting in an armchair by the window in his mother’s apartment. “But they still didn’t have to do this. They rehabilitated thousands of orphans and saved many lives. My mother, and thousands of others are alive today because of them.”

Ester Wasserstrom listens quietly, her gaze flicking to the photographs of her great-grandchildren in her apartment, and smiles. n