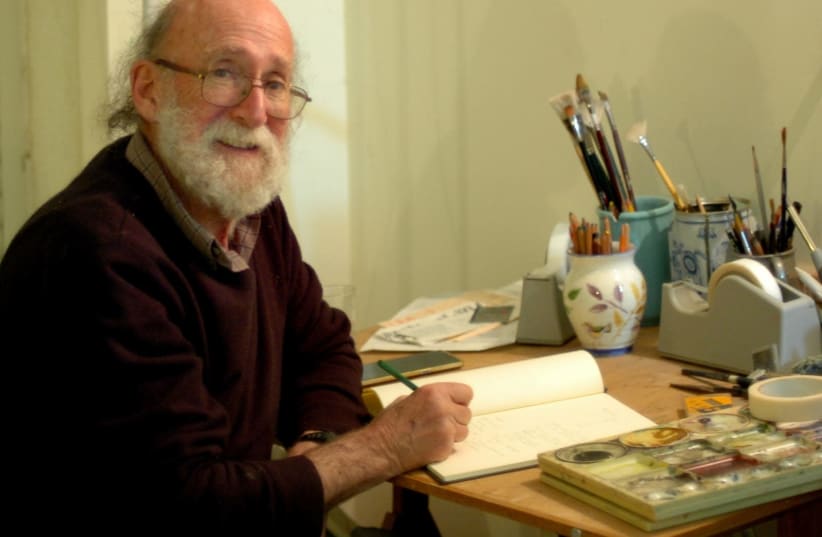

Derek Stein, who passed away suddenly at Shaare Zedek Hospital on February 27, 2020 at the age of 81 and was laid to rest on March 1 in Beersheba, was a beloved artist whose talents were highly regarded by his devoted students and the many collectors of his work. His paintings, until the last years of his working life, were confined to the difficult medium of watercolor. Just how difficult this medium is can be verified by trying making a totally smooth wash, from paint and water. This is a very common exercise taught in art school.

Stein became a master of this medium, even though he was mainly self-taught. His passing, and the lack of a wider appreciation in Israel, is a sad reflection of the state of Israeli art, particularly for artists who come from outside the country.

Stein was born in Northern England, in Newcastle, to a family of doctors and pharmacists who had come from Europe, and, from his mother’s side, from Palestine.

“To take up art,” according to his daughter Ashleigh, “took a lot of guts.”

Like many traditional Jewish parents, Stein’s were not keen on their son becoming an artist. Instead, he found himself in the nearby yeshiva at Gateshead where he stayed for a year and a half. When he realized that this was not for him, he emigrated to Israel in 1969, where he was drafted into the army in the anti-aircraft unit of IDF. He then studied English Literature at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and for a short while worked in advertisement. But the call of art was too strong and he soon joined a class taught by the well-known teacher at the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts, Joseph Hirsch.

Hirsch’s influence was crucial in his development. In a seminal book on the teachings of Hirsch, Stein wrote the following appreciation: “If I would have to characterize his methods in a few words, I would stress first and foremost the respect for the student, and the readiness to let the student be himself and arrive at things in his own way. What touched me most in Hirsch, the man, was his mix of utter seriousness and self-irony.”

Later, in his own teaching, these same elements emerged. As one of his students, Jackie Kyram, noted: “He used to gently coax me to try again when I became frustrated. Always encouraging, he would look thoughtfully at the artistic confusion I presented him with and asked how I could take the painting to a different place. He always gave me encouragement and the confidence to believe in myself and carry on.”

Further testament to his teaching abilities came from another student, Marion Kunstenaar, who had spent a lifetime painting, but for whom Stein’s classes changed her life.

“He was so fluid,” she said. “Never demanding, rather asking about a subject ‘What do you feel?’ He was a soul. He was almost not a teacher – in the best way, of course. When I asked him at one point: ‘Do you mind if I go my own way?’ (I was particularly interested in abstract painting), he replied with an accepting smile. He wanted his students to discover their own style of doing things. This is what made him a great teacher.”

His teaching went side by side with his own art. Although deeply influenced by Hirsch, he soon developed his own style,, producing hundreds of watercolors of portraits, landscapes and still lifes.

He was drawn to watercolor in the same way as he was drawn towards the study of Zen; both demand paradoxically strict discipline and spontaneity. In his house in Jerusalem, a number of original Far Eastern paintings are hanging, a memento of his journeys to the Far East with his wife, Jackie.

He was also very sensitive to color, and taught his students how much colors influence each other. This sensitivity to the delicacy of tone and line was one of the disciplines he absorbed from his beloved teacher, Joseph Hirsch. No less an influence was that of the English tradition of water colorists such as John Cotman and William Turner of Oxford. Stein followed this tradition, but certainly not pedantically.

His work has the freshness and spontaneity of these great masters but show a powerful individuality which is all his. The uniqueness of watercolor is in the way the paint is applied to the paper. Once a mark is made it is there for good. Over-working it ruins it. It has to remain in its pristine state. That is the beauty of watercolor and that is why it has to be planned carefully so that the final effect is one of effortless spontaneity. To reach this level of composure takes a great level of dedication. Stein had that in spades.

As can be seen in these examples of his work – whether of still lives, landscapes or portraits – the central features of them all is the integration of the evanescence of the subject, its apparent fragility, against the fact that a passing phenomenon has been captured forever. This gives the watercolor its lightness, and its vitality.

A glance at his work shows these aspects of his craftsmanship. The lightness of touch is everywhere apparent. Whether he is painting a vase of flowers, a lush landscape or a naked female model, the effect is similar. We are witness to an artist who knows what is important, what to put in and what to leave out. There is an economy of strokes; no more, no less.

At its best it is a vision of surprise, of amazement. As his friend, the poet Simon Lichman, put it, “to be caught off guard by your point of view.”

The viewer is taken aback: “How was that vase on the table achieved?”

Lichman was a steady and steadfast friend. At his funeral, he summarized his feelings towards the artist: “He was consumed by his vision, constantly sorting out the world around him in terms of the canvass or paper block no matter what he was doing – painting or cooking supper for the family. Sometimes on our way home from a picnic he’d stop to paint the sunset over Khirbet Sa’adin, for example, or the way the light played through the pines of the Jerusalem Forest.”

As to the central characteristic of the man himself, Lichman reflected: “He was as quiet and unassuming as his paintings. If we compare his output to the long tradition of Western watercolor, it seems a criminal oversight that he is isn’t given his due respect.”

Art for Stein was an ongoing challenge and in this endeavor, he remained true to himself, never compromising to suit the general taste. This worked against him in that his natural diffidence and modesty led to a reluctance to market himself and stake a deserved claim for recognition in the wider art world.

His wife and children are planning a larger retrospective of his work, and perhaps a catalog of his many paintings, alongside extracts from his unpublished notes.