I request your company, dear reader, in traversing a path among the bubbling and brewing wellsprings of my mind. For despite the many pitfalls, slips, and slides that exist as my thoughts are formed – requiring all sorts of gymnastic leaps and bounds to get from place to place – this path I show you is one that I have traversed long enough that I feel the path has been paved to the point of providing fairly certain footing.

This pathway I describe is an exercise in perception of our world and the potential within. Using two tools unique to humanity, observation and rational thinking, making it one of the more holy pursuits mankind can achieve, I seek to describe a system for positive growth in society. In short, my effort here is nothing less than to add perspective to the direction of humanity’s search for Utopia on earth.

The path begins with a single question – were I able to create a simulation wherein humanity is directed to our best society, what factor or factors would need to be applied for that to occur? The question as I perceive it, recognizes the importance of each person’s uniquely lived experience, individual talents, and separate part in forming our societal whole. As such, choosing to give everyone a hive-mind where objective truth is understood by all would not be an acceptable result. Rather, no factor about humanity’s characteristics as a whole and individuals characteristics – positive and negative – should be modified in this mental exercise. For our goal is not to imagine what Utopia would look like, but describe a system that would lead people to a society closer to that we imagine as Utopian. In fact, risking being ill-mannered, I would request you, dear reader, set aside this paper for a moment to attempt to answer this question on your own: Assuming no variable about the world is changed, what system could we put in place that would lead us as a society toward a better (our best) future?

The first option that pops into mind is simple: Let us find the best minds in the world and have them lead us. Such an answer would seem to answer all our problems. Climate scientists would direct us in how to protect the environment. Economists would direct the money flow. Infrastructure would be built with the advice of Engineers. Dietitians would direct our health food choices. Etcetera.

There are several issues with this perspective in my eyes.

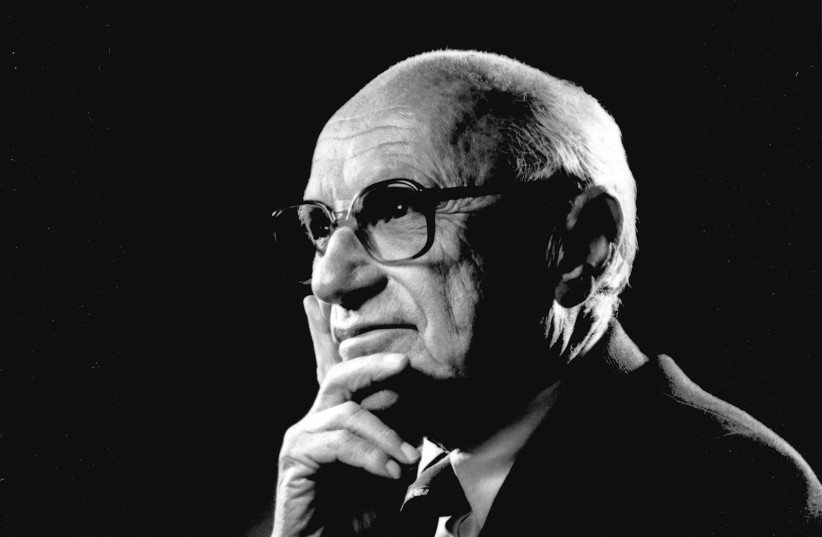

The first is that it removes choice from most of humanity. And while this has its appeal (even Milton Friedman, author of Freedom to Choose, recognized how putting the weight of choice on the shoulders of others is certainly calming) the importance of individual choice and freedom of choice is no less part of individual lived experience than the human experience itself. Right choices and wrong choices both lead to individual growth and are an integral part of the lived experience.

Second, the loss of freedom is of particular concern. If there is no freedom, humans can claim no difference between themselves and pre-programmed robots. Again, despite the appeal of foisting the weight of choices onto the shoulders of others, this removes the very individual freedoms that make us human.

Thirdly, and this from a utilitarian perspective, this model chooses to ignore the differences in opinions between experts in a field. Even if two scientists agree on a fact, how they would respond is hardly likely to be exactly the same.

Finally, this option doesn’t take into account the warring interests – even assuming the leaders themselves are wholly altruistic – between the different fields. The goals of the economist who seeks to increase public goods and services is on a wholly different plane than that of the preservationist or scientist. That the two fields will find a middle ground can barely be considered a comfort – for what will happen when only one side is in fact right?

Setting aside the above option as a possibility therefore, another model is thus called for in order to solve our problem. With some wrangling, another thought rises to the top.

Theoretical models may take certain axioms as a given, even if the very model is a flawed concept. For example, economic thought uses the concept of ceteris parabis – all else being equal – in describing economic phenomena. In our case, I’d like to presume that government fulfills its primary function of maintaining a monopoly on force.

Then, recognizing as Thomas Paine does that government and society are separate entities so we can remove force from the equation, we can look at the world through a lens of benefits. A theoretical model based wholly on the metaphorical carrot can in this fashion emerge.

Assume that every human being is born an adult and capable of making his/her own decisions and we then endow each person with a certain number of points. Each person can provide these points to another whom he considers having done something positive. With this model, subjective truth becomes an important part of the equation. People receive positive feedback from others as an indication that what they are doing is positive. A person who cleans up litter may receive points from those around him. A person who bakes bread for another will receive points in thanks. Activities that are valued receive points by society and in this manner, those activities that achieve the most votes of the most people will create the drive for future activities by members of the society. In order for this model to succeed, however, the number of points needs to be limited to a finite number. For if the points simply renew each day, there is no value in receiving the points. Only in the importance of circulation of the points does this model rest.

Inevitably the system will change, however. As people seek to gain points, actions will become transactional. Some will choose to act on behalf of another on the condition that he will receive points in return. A chase to attain points will engender an agreement between the two sides before an action will take place: Points for an action or product that another values. Altruistic actions with unexpected reward will become less likely as people chase after ulterior motivations of point collection. While this may seem to be a failure of the proposed system, one must ask – If the end goal of people doing good on behalf of others is still achieved, does this not still fulfill our qualifications?

As for the fact that selfish desires drive the transaction, Adam Smith points to the very confluence of desires and reciprocal nature as a uniquely human trait. Being that two people are both helping each other through compensation and the end result is an unqualified “good” for both sides, this uniquely human activity might easily be described as “righteous.”

Differences between the importance of some actions over others raises another question. How will society recognize this hierarchy of importance if everyone simply receives one point for doing something positive for another? The clear answer to this is that there is no limit to how many points a person can provide another.

An individual may value baked bread at two points, for it fulfils a personal need, but the picking up of litter and the cleaning of the streets at one point because clean streets are a pleasant sight to behold but cannot be considered a necessity by any means. Despite the difference in points one would achieve for baking bread for another compared with street cleaning, this would not categorically define baking bread as a more worthwhile endeavor. For while true that every individual action done by the baker is valued by individual people double that of the street cleaner, the street cleaner with each action benefits more people. So in terms of actual potential for earning points, the street cleaner might be more likely to receive more points than the baker. The drive to achieve more points will cause even the most selfish in society to provide as many services for others as possible.

In this fashion, the system of voluntary points would seem to lead us as a society to a greater and more giving society.

Wait.

Just a moment.

Swap out points for money and we’ve just described the system of capitalism?

Indeed. It appears we have.

Meir Liberman has a master’s in Politics and Government from Ben-Gurion University and is currently studying Law at Tel Aviv University. As a perpetual student with broad interests in economics, science, and political philosophy, he has a passion for thinking both inside and outside of the box.