There’s no doubt about it. The past year, 5781, was one of the most difficult in recent memory. We experienced further waves of the pandemic, with so much loss. We endured another Gaza war, accompanied, predictably by a vicious backlash against Israel’s right to defend itself. Political instability and economic uncertainty have become almost endemic globally.

The pandemic, in particular, has overturned all our certainties. Who would have thought that modern, industrialized, powerful nations could be brought to their knees by a virus? Who would have thought that children could be kept away from school for months on end right across the globe? Who would have thought entire countries could be “locked down”, industry and commerce frozen, entire populations confined to their homes?

It hasn’t all been doom and gloom. The Gaza war ended and tensions calmed. And even as the virus persists, the global vaccine rollout has been remarkable, and results continue to show that the vaccine provides effective protection from hospitalization and serious illness.

But even with these blessings, it has been a traumatic year for us all and uncertainty persists.

Moments of crisis provoke within us some of the deepest questions – questions that, when life is more stable and certain, tend to be buried under the comforting hum of daily activity. These kinds of questions arise at times of personal upheaval – the loss of a close family member or friend, debilitating illness, the loss of a job.

Trauma jolts us out of our complacency, upends the certainties in our lives and forces us to reflect. When all of our expectations are overturned – when everything becomes so unpredictable, so unfamiliar – we are compelled to re-examine life and everything we thought we knew. We ask ourselves searching questions about the very nature of our existence: What is the purpose of life? Are we here merely to survive? What do we want from life? Why are we here? Is there some higher meaning behind it all?

We can try to ignore these gnawing questions; pretend they don’t exist. We can distract ourselves with our daily routines or find diversion in the entertainment industry, so expertly developed to deliver escapism from reality. We can bury the deepest, most troubling questions about the meaning of our lives. It is a real temptation.

It is a temptation that Noah succumbed to when he tried to face the future after the great flood that destroyed the world. It was the most traumatic experience humanity has ever endured; a torrential downpour that continued unabated for weeks and literally washed away human civilization.

Noah and his family were the only survivors. They survived the flood by taking refuge in a miraculous ark, which provided a sanctuary from the turmoil raging outside. In the ark was everything needed to rebuild the world after the flood, including representatives from the animal kingdom, and even branches of different trees and vegetation.

When the storm subsided and Noah left the ark, one of the very first things he did was to replant the vine, which he had watered and nurtured on the ark. Later, he harvested the grapes, made wine and drank himself into oblivion.

He sought solace and escape from the trauma he’d endured through the numbing effect of wine. Our sages in the Midrash take him to task for this action and say he should have instead planted an olive branch – which he had also nourished on the ark throughout the flood.

What is the essential difference between the vine and the olive tree? They symbolize different responses to trauma and turmoil. The vine represents the response of escapism; of seeking to dull the pain and avoid the difficult questions. Wine allows us to distract ourselves from difficult predicaments so that we can go on with life as if nothing happened. As if our world was never really turned upside down.

The olive tree is the opposite response. It produces olive oil, which served as the fuel used to light the menorah in the Temple. The olive tree thus represents wisdom, light and clarity. It represents our desire to confront pure truths about the meaning of life, rather than retreating into giddy delights and escapist pleasures. In his great moment of truth, Noah instead chose escapism.

We have the same choice as we begin to emerge from this time of crisis and uncertainty. We can choose to distract ourselves with chores and work, or escapist pursuits, and avoid all the profound questions. Or we can face the truths of our existence head on.

The urge to avoid the truths of life can sometimes feel irresistible. But it is short-sighted. Eventually, escapism is really no escape at all. Without confronting these existential questions, our anxiety will simmer beneath the surface, and we will always be haunted by their presence, lurking at the back of our minds like shadows, waiting to come out at the next crisis.

And there will always be another crisis. We all, one day, have to face the greatest personal crisis of all – death itself, which no one escapes. Death forces us to confront the most painful existential questions of all. If life is so fleeting, does it mean anything? What happens to everything we achieve in our lives? Does it disappear with us? What happens to us after death? Is there any purpose in our scramble for survival if it ultimately ends in death? It seems so futile.

These are disturbing questions, which are much easier to pretend to ignore. But the ongoing crisis we are all going through raises them again. We can choose the path of avoidance and distraction like many did after the trauma of the Spanish Flu when societies slipped into the escapism of the Roaring Twenties, which – in profound symbolism – ended in the Great Depression. Let’s not make the same mistake as that generation – the mistake Noah made at the dawn of civilization. Escapism offers short-term-relief from discomfort; but ultimately, we cannot escape from reality.

We will never be truly happy until we find the meaning and purpose of our lives. We are meaning-seekers in the core of our being. The deepest human drive is the will to find meaning in our lives. If we don’t satisfy this need, we will never find fulfilment, contentment and inner peace. We will never find true happiness. This is one of the most important insights of modern psychology – gifted to the world by a Jew who lived through the darkest chapter of our history.

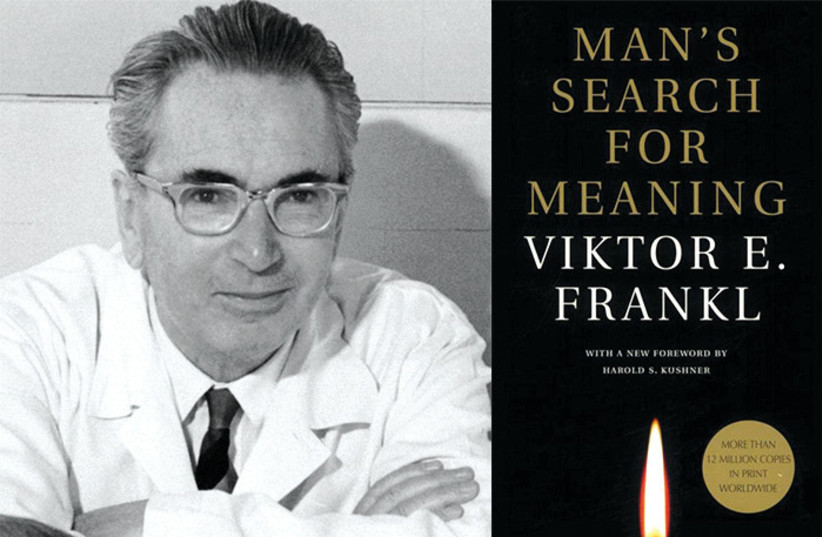

I am, of course, referring to Viktor Frankl – the psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor responsible for one of the most remarkable breakthroughs in modern psychology.

Born in Vienna in 1905, his life’s work of understanding human nature began before the Second World War. He attempted to answer what is probably the most important question in understanding who we are – what is our deepest need? What is the one thing that drives us and fulfills us more than anything else? This was a source of debate among the great psychologists of the time. Sigmund Freud argued that the quest for pleasure is the most powerful driver of human behavior. Alfred Adler believed it to be a quest for power. But for Viktor Frankl, the deepest human need is for meaning.

It was on this basis that he founded a new school of thought in psychology, which he called logotherapy, from the Greek word for meaning, “logos.” Logotherapy is centered on the principle that our will to find meaning in life is our primal human drive.

Take a moment to consider this radical idea – that the deepest human need is for meaning and purpose.

Frankl had already arrived at this insight before he was sent to the concentration camps. But it was his experiences in Auschwitz and Dachau that gave him the real life experiences to confirm his theories. In the camps he was stripped of everything – his possessions, his dignity, adequate food and shelter and the people he loved. And in that bare, stripped down mode of existence, he was forced to confront the most basic aspects of the human condition.Frankl’s groundbreaking observation, as documented in his opus, Man’s Search for Meaning, was that in many cases the people who survived the hell of Auschwitz were those able to find meaning and purpose in their dire circumstances:

“We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms – to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

Our deepest human need is not for survival for its own sake. And when we focus only on our physical urges and selfish desires – the pursuit of pleasure, the quest for honor and power – we will never be satisfied. Without meaning, we can never be happy. Without purpose, peace of mind will continue to elude us. If we don’t devote ourselves to our own search for meaning, emotional and psychological pain will always pursue us.

So let’s use this moment of global and personal crisis as an inflection point to begin our search for meaning. Let’s be brave enough to ask ourselves the most difficult question of all: What is the meaning of our lives? What is the purpose of it all? Is it merely survival? Is it to experience as much pleasure as possible before we die? Is life – as Malcolm Forbes, the US media tycoon, once cynically remarked – “a game, and whoever dies with the most toys wins”?

WE ARE blessed because we don’t have to confront these profound questions alone. We stand on the shoulders of the generations who came before us. We are the proud descendants of those who stood at Sinai when God gave us the Torah – our spiritual inheritance, which has been loyally transmitted from Jewish parents to their children across historical eras and continents.

It is our most precious possession and contains all the secrets about the purpose of life from the One who created us. It teaches us that our lives are not an accident of nature; we originate from a purposeful act of creation: “In the beginning, God created heaven and earth.” Our world is not a random accumulation of molecules – there is a grand design to the world and, therefore, grand meaning to our existence.

If human life is the product of a random accident it is, by definition, without purpose or meaning. Randomness and purposefulness are opposites. They are incompatible. God may have employed some form of evolving process in creating the world, but it was not random, it was directed by an all-knowing, all-loving Creator, with meaning and purpose.

Our Torah also teaches us that we are not simply physical beings, not merely highly intelligent animals, but that we have a spiritual dimension – what we call a soul. In fact, our tradition teaches us that we are essentially a soul clothed in a body, and that we originate from another world – a spiritual world where there are only souls – and that God sent us into this physical realm on a mission to do good.

This explains Frankl’s insight that the human being is primarily a meaning-seeking creature, unlike any animal. It explains why our deepest need and most powerful drive is to find meaning. If the human being is merely a randomly formed physical creature with no qualitative difference from animals except in level of intellect, then from where does the drive for meaning come?

It follows that the purpose of life is not mere survival; that life is not merely about self-preservation and self-gratification; that it is not an anarchic struggle of the survival of the fittest or about pursuing pleasure or power for their own sake. It is about the search for meaning, for a higher purpose, for something greater than ourselves.

We are blessed as Jews to have received from the generations who preceded us the ultimate blueprint for realizing our meaning and purpose – the Torah, with its wisdom and mitzvot. And it comes directly from the One who created us, and who knows us better than we know ourselves. From the moment we wake up until the moment we go to sleep, it guides every dimension of the human experience; infusing even the most mundane moments with sanctity and significance; imbuing us with compassion and kindness, courage and faith; and helping us to lead a moral life, a life of contribution, a Godly life.

It also offers us an eternal legacy to defeat death. If the purpose of life is survival and self-preservation, then by definition it is set up for failure, because in the end we all die. The inherent problem with finding meaning is that life is temporary and fleeting.But our Torah teaches us that death only affects the body; that our soul, our essential self, is immortal. God sent our souls down to this physical world to inhabit a body, and we return to Him after a short span on this earth, taking with us all the mitzvot we did while we were here. Every act of kindness, every word of prayer, every moment of self- restraint, every word of encouragement and gesture of kindness, every act of integrity, every Torah thought learned, every cent given to charity, every minute of Shabbos kept, every brocha said, comes with us to the eternal world as our legacy. We leave behind our bodies and all our physical possessions, and we take with us our mitzvot as we journey back to the world of souls from where we originated.

We also take with us all our mistakes and sins; God gives us a place in His heavenly world in accordance with what we accomplished – good and bad – here on earth. God also gives us great reward for all the suffering we endured in this world with dignity and faith. No suffering is wasted. It accompanies us as an eternal merit on our eternal journey.

Viktor Frankl leaned on his spiritual inheritance, handed down through the generations, at key moments of his life during the war years to give him insight and meaning. His mother could actually trace her lineage as a direct descendant of the great French medieval sage and commentator, Rashi, who in turn could trace his lineage directly to King David. In the introduction to Man’s Search for Meaning, he tells the moving story about why he chose not to accept an immigration visa from the American consulate in Vienna that would have enabled him to escape pre-war Europe. Though the storm clouds were gathering, he writes that he did not want to leave his parents behind. He was left with an agonizing decision and decided to look for “a hint from heaven”:

“It was then that I noticed a piece of marble lying on a table at home. When I asked my father about it, he explained that he had found it on the site where the National Socialists had burned down the largest Viennese synagogue. He had taken the piece home because it was a part of the tablet on which the Ten Commandments were inscribed. One gilded Hebrew letter was engraved on the piece; My father explained that this letter stood for one of the Commandments. Eagerly, I asked, ‘Which one is it?’ He answered, ‘Honour thy father and thy mother that thy days may be long upon the land.’ At that moment I decided to stay with my father and my mother upon the land and to let the American visa lapse.”

And he also shares how his heritage gave him meaning and purpose in the death camps:

“I found myself confronted with the question whether under such circumstances my life was ultimately void of any meaning. Not yet did I notice that an answer to this question with which I was wrestling so passionately was already in store for me, and that soon thereafter the answer would be given to me. This was the case when I was to surrender my clothes and in turn inherited the worn out rags of an inmate who had already been sent to the gas chamber immediately after his arrival at the Auschwitz railway station. Instead of the many pages of my manuscript, I found in a pocket of the newly acquired coat one single page torn out of a Hebrew prayer book, containing the most important Jewish prayer Shema Yisrael. How should I have interpreted such a ‘coincidence’ other than as a challenge to live with my thoughts, instead of merely putting them on paper?”

And so, as we grapple with all we have experienced over the past year, let us, too, turn to our Torah legacy to guide us towards a life of meaning and purpose. Let us not allow this time of crisis to pass without using it to change our lives for the better. Let’s act now. Let’s make 5782 the year of meaning and purpose.

At the start of this new year, let each of us, as individuals and families, dedicate ourselves to finding meaning every day through our spiritual inheritance - to pursuing meaning not escapism, purpose not distraction.

We must think of practical measures. What new mitzvot are we going to take on this year? The more we learn, the more mitzvot we can do, and the more meaning we will find. The 613 mitzvot are a formula for developing, enriching and deepening our most precious relationships – with others and with God – with gratitude and appreciation, love and respect.

And they give us the opportunity to find meaning in everything we experience. You see the ocean, hear thunder, eat a fruit – you say a bracha; you meet another person – you greet them warmly; you light Shabbat candles and switch off your phone to welcome in the magic of the day. Every moment of every day is another opportunity to find meaning.

Frankl himself makes the point that meaning and purpose is not some amorphous or abstract concept – it’s something we need to consider at every moment. It’s something we can bring to every act we do, every thought we think, every word we say. That is why we are so fortunate to have Torah and halacha with all its details guiding us in this noble endeavor every moment of every day.

Finding our meaning through the Torah is not only through the specific mitzvot we have. It gives us the ‘why’ of life. It is about an entire worldview, which has the power to infuse everything we do with the inspiration that comes from a sense of mission.

It can transform parenting from futile, circular drudgery into a calling. We grow up, earn a living, get married, have children and eventually die so that our children can do the same thing all over again. And yet, changing nappies, doing school lifts, helping with homework, ensuring there’s a roof over their heads and clothes on their body and food in their stomachs – becomes the fulfilment of the awesome mitzvah of having and raising children who will continue our Divine legacy and take the values of our people into the future. We make it our sacred mission to teach them and train them in a Torah way of life. This is the stuff of legacy and eternity. All of this is part of our mission and purpose.

Torah values can also transform our work. We can strive to earn money to buy more “toys” for ourselves. Or we can work and earn a living in order to support our family with dignity, give charity, support Torah education, provide people with jobs, serve clients with integrity and pride, and help society through contributing to a growing economy. Any job, whether it’s a business executive, employee or professional, can contribute to making the world a better place. Seen from this perspective, our work becomes a vital mitzvah.

This Torah way of looking at life can also infuse with meaning our mission to build and support our Jewish communities, in Israel and in the Diaspora. We aren’t just focused on survival for its own sake. Our mission is to nurture and sustain vibrant Jewish communities that give expression to – and the opportunity to live by – our eternal Jewish values received at Sinai. Our shuls, schools, welfare institutions and security organisations are part of an eternal legacy for us all, as we connect ourselves to Jewish communities throughout the ages fulfilling our Divine mission to carry the light of Hashem’s values in the world.

This approach of finding meaning through Torah also shifts how we confront antisemitism. We have to define our Jewish identity on our own terms, and not be defined by those who hate us. We need to give our children a real reason to want to be Jewish. We have to give to our children and grandchildren an inspired Jewish identity – one they will be proud and excited to be part of. There’s no meaning and purpose in survival alone. We need to be able to communicate to ourselves and to our children why we want to survive. It all starts with ‘why’.

Knowing the “why” is also important when it comes to our Zionism. Why is a Jewish state important and precious? It must be about something more meaningful than mere survival. Why would it be a problem if Jews disappeared from the world? Unless we can answer this disturbing question, there is no meaning in the actions we take to survive. Only by answering it can we even begin to justify the sacrifices of Jewish history. When Theodor Herzl founded the modern Zionist political movement, he was motivated to solve the problem of antisemitism in Europe. And yet, today, far from having solved antisemitism, the existence of Israel has become the focus of it. Instead, we have a far more inspiring vision to rally around – a high-functioning, successful Jewish state established on the ancient land promised to our ancestors, serving as a national platform to fulfill the Divine mission and destiny of our people.

And in a more personal way, through the prism of Torah, every situation, every moment, is ripe with meaning, pregnant with potential. Every physical and emotional experience we enjoy invigorates us as we feel gratitude to God for His bountiful world. Every one of our most precious relationships we learn to appreciate in new ways. Every illuminating thought and spiritual connection inspires us. Every challenge we overcome and every moment of suffering we endure with fortitude becomes meaningful and gives us pride in our accomplishments, which God is recording for eternity.

By imbuing our entire existence with meaning, we find fulfillment and true happiness. But it all starts with having the courage to face the biggest questions of our existence. The answers to all our deepest questions lie within our Torah. All we need to do is find them, accessing the power to transform every moment of life into something crackling with meaning and purpose.

And now is the time of year to do it. We’ve just come out of Yom Kippur, when we reflected on the year that was and looked ahead to the year to come. We stood in shul, admitting to ourselves that nothing is certain, not even life itself. We acknowledged our frailty and uttered the stirring words of U’Netaneh Tokef: “Who will live and who will die... who will enjoy tranquility and who will suffer… who will be impoverished and who will be enriched… who will be degraded and who will be exalted.”

Reflecting on these moving words, and on everything we have been through, we have the same choice that Noah faced when he left the ark. We can plant a vine or an olive tree. We can pursue escapism or truth. We can confront our mortality and the perilous fragility of our existence and the deep existential questions that evokes. Or we can seek solace in escapism, allowing the feelings of discomfort to pass and the existential questions to go unanswered, hoping these questions will fade, and that our lives will return to a state of settled calm and certainty.

Let us choose to be bold. Let 5782 be the year we set our lives on a new path. Let this be the year of truth. The year of meaning and purpose. The year of change. The year of blessing.

The writer is Chief Rabbi of South Africa.