SOME 118 years ago, a Jewish socialist society was born in Britain through the efforts of a journalist called Kalman Marmur. A year later, in 1903, Poale Zion as it was known, became officially affiliated to the Labour Party. Thus, together with its successor, the Jewish Labour Movement, it has the honor of being one of the longest standing affiliates of the British Labour Party in the party’s history. The contribution of Britain’s Jews to the development of the party in these years and in the decades to follow, is a matter of proud record, a contribution unhappily ignored in the most recent past.

Shortly after its inception, Poale Zion formed branches in several trade unions including the Garment Workers and the Cabinet Workers in which many Jewish immigrants found a home in the early part of the twentieth century. Union activity went along with membership of the Labour Party to such an extent that Poale Zion was invited to participate in the formation of Labour’s War Aims Memorandum in World War I. The Memorandum set out the Labour Party’s vision for the future of the country once the war was over. It included a section on the Jews and Palestine, recognizing the rights of the Jewish people to a homeland and preceding the Balfour Declaration by several months. The Labour Party was therefore the first political party in Britain to embrace the Zionist mission.

In the mid 1920’s, the World Union of Poale Zion established an official office in London, headed by Shlomo Kaplansky and David Ben Gurion, to oversee the activities of the various PZ groups around the country, which by then included young Poale Zion and a women’s group known as Pioneer Women, many years later, Na’amat. In 1957, PZ promoted the formation of the Parliamentary Friends of Israel, whose members read like a five star list of prominent MP’s all of them Jewish: Ian Mikardo, Leo Abse, Maurice Orbach, Sammy Fisher, Leslie and Harold Lever, Eric Moonman, Greville Janner, Maurice Miller, [who formed a Scottish branch of PZ] and many more. The written constitution of PZ, like that of its successor JLM, committed its members to the ideals of social justice, equality and freedom and opposition to any form of fascism, racism and antisemitism, values indistinguishable from those embraced by the Labour Party. So when did opposition to antisemitism in the party become less of a basic value?

The answer, sorry to say, is from its inception, which could also be said of the Conservative Party, the British establishment and society at large. But for British Jews, it is particularly disturbing in view of their contribution to the development and history of the Labour Party. Keir Hardie, the founder of the party and a Labour MP, had antisemitic views summed up in the following extract from one of his speeches. ‘Wherever there is trouble in Europe, wherever rumors of war circulate and men’s minds are distraught with fear of change and calamity, you may be sure that a hook-nosed Rothschild is at his games somewhere near the region of the disturbances.’

Even the revered socialist thinker Sidney Webb, thanked heaven there were no Jews in the Labour Party [in fact, there were many] because, he maintained, ‘there is no money in it,’ a sentiment echoed by the some time Labour Foreign Minister, Ernest Bevin, who famously remarked on the, “number of Israelites engaged in the black market.”

This popular conception at the time of Jews as capitalists, fed into the anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist minority creed, which spilled over into anti-Zionism following the 1967 war.

It took Harold Wilson, who became Labour prime minister in 1964, to voice opposition to the rumblings of antisemitism and anti-Zionism in the party, and to steer it towards a pro-Israel stance supported by the Labour Friends of Israel and the many Jewish members of both Houses of Parliament, which prevailed until the last few years.

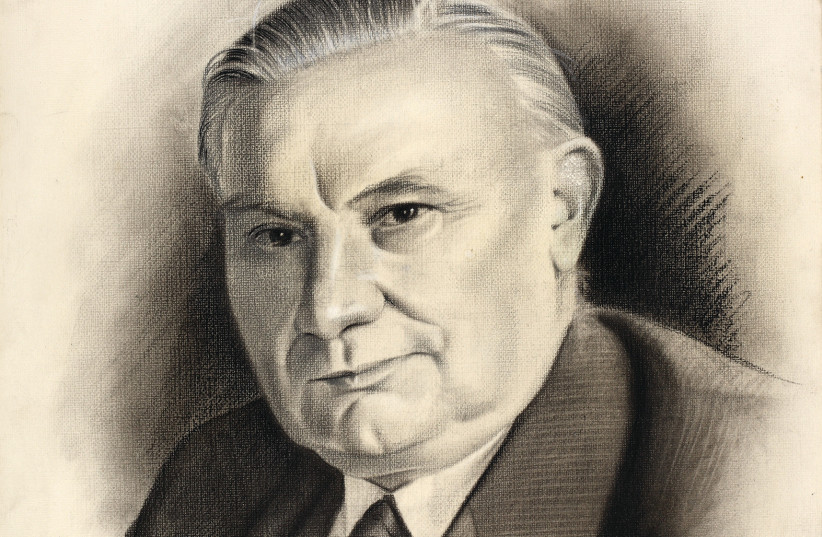

One of the earliest examples of a reaction to an antisemitic remark by a Parliamentarian, is provided by Emanuel [Manny] Shinwell. He was one of those MP’s who came into politics via the trade unions. Born in the East End of London, one of thirteen children to Jewish immigrant parents, he entered Parliament first in 1928, lost an election in 1931 but returned in 1935 and remained an MP until 1970 when he was elevated to the House of Lords. He was the most prominent Jewish Labour MP of his time, serving under various Prime Ministers and holding a variety of ministerial posts. During one of his typically forthright contributions in the House of Commons, he was interrupted from the Opposition benches, with an instruction to go back to Poland. Seeing this as an antisemitic remark, Manny crossed the floor of the House and punched the offender in the face, for which he was, naturally, called to order by the Speaker.

Move forward seven decades to his niece, Luciana Berger, former Labour MP for Liverpool, Wavertree She was driven out of the party in 2019 by virulent antisemitism, eventually dealt with not by a physical reaction on her part, but by an independent investigation by the Equality and Human Rights Commission. Luciana Berger had been an MP for nine years, had headed the Parliamentary Jewish Labour Movement and had held various Shadow ministerial posts. In the years 2018-2019 she was subjected to online and in person abuse by fellow members of the Labour Party, was threatened with acid attacks, stabbing and rape to the point where she had to have police protection. In her evidence to the Commission she accused the party of “a culture of bullying, bigotry and intimidation against Jewish people from within its ranks’ and that ‘every step of the way, Jeremy Corbyn [the party leader] enabled this to happen.”

For the first time in living memory, the issue of antisemitism became a topic of national interest during the general election in December 2019. Newspaper headlines, television discussion groups, party political election broadcasts all concerned themselves with what was going on in the Labour party and its apparent prejudice against its Jewish members. As a result, a poll taken among Jewish voters in advance of the election showed that 93% of them would not be voting Labour. In any event, the party suffered a humiliating defeat and Jeremy Corbyn resigned as its leader.

The Equality and Human Rights Commission investigation totally endorsed the Jewish Labour Movement’s claim that the Labour Party under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn had been institutionally antisemitic. The new leader of the party, Keir Starmer, whom I know from my own correspondence and meetings with him to be deeply concerned by expressions of antisemitism among party members, lost no time in withdrawing the Parliamentary Labour whip from Mr. Corbyn, whose membership of the party was also suspended. The new leader made it abundantly clear that he accepted the findings of the Commission and made a pledge to the Jewish community that there would be zero tolerance of any kind of anti-Jewish prejudice on his watch

The Commission’s conclusions and the actions of Starmer came as a huge relief to the Jewish community, among others because the apparent rise in antisemitism in the party looked like a betrayal of the loyalty it had given to it over the years. Why it exists at all is a much debated question, probably best left to the psychologists.

Footnote: Jeremy Corbyn was readmitted to the Labour Party following a written apology to the Jewish community, but he is still not permitted to sit in Parliament as a representative of the Labour Party.