The Gershom Scholem Reading Room at the National Library of Israel (NLI) – the world’s premier collection of rare books dealing with kabbalah, its sister studies of hasidism and Sabbatianism (the study of false messiah Sabbatai Zevi), and comparative mysticism in the gamut of the world’s religions – is preparing to move. Leaving the Hebrew University’s Givat Ram campus after 40 years, it will relocate two kilometers to the northeast to its permanent home at the new NLI on Ruppin Boulevard, symbolically situated linking the Knesset and the Israel Museum.

Library director Oren Weinberg can’t find enough superlatives to describe the ever-growing collection of kabbalah esoterica, which today includes 35,000 volumes in Hebrew, English, German and many other languages. “It’s one of the jewels in the collections of the library,” he smiles. And the Gershom Scholem Reading Room’s new space, more convenient relative to the general Judaica collection, will be “a magnificent reading room to keep on nurturing it,” he promises.

“It is a really beautiful space with room to grow,” he enthuses of both the mystical reading room and the new National Library’s landmark building as a whole. “It will be much more accessible. We hope people will see it as home.”

Designed by the Basel, Switzerland starchitects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, best known for their “birds nest” Beijing National Stadium built for the 2008 Olympics and used in this winter’s games too, the Tate Modern in London, and the Prada Store in Tokyo, the facility will be a multi-purpose cultural cathedral featuring an array of user-friendly venues from a café to a conference center.

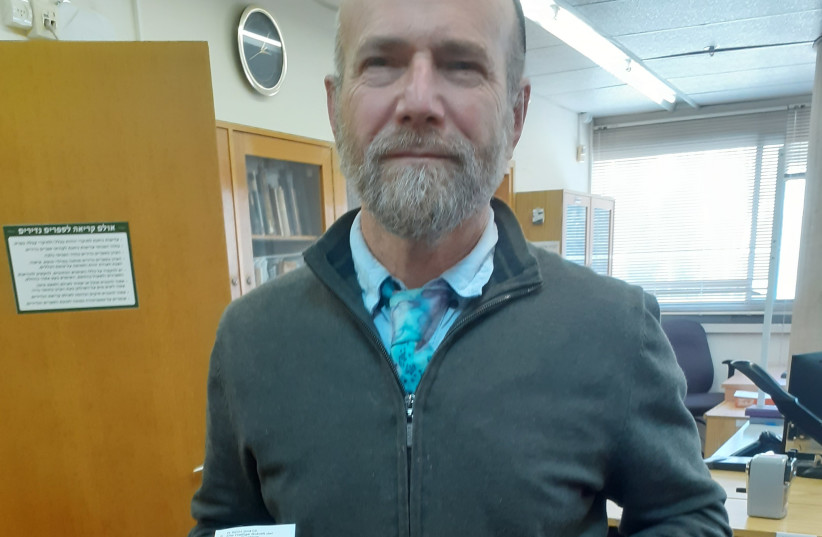

Zvi Leshem – the Cleveland-born scholar who has been the director of the Scholem collection since 2011 – beams with excitement about the move, adding it will take some six months to transfer the library’s five million books. Neither an ivory tower for academics nor a tourist attraction for those seeking out spiritual exotica, the Gershom Scholem Reading Room is a haven for scholarly research and study, he explains.

The reading room serves the readers, he clarifies, who range from haredim to Christian Arabs to scholars from the Orient. “It’s really common here to see a guy without a kippa and a guy with long payess sitting together. There’s a lot of symbiosis. They work together really nicely. The Scholem collection is a really nice multicultural space because we have a huge variety of people here.”

Sometimes the holy sparks fly in unexpected ways, Leshem adds. “A few weeks ago a couple got engaged in the reading room.” It was an intimate moment complete with a red carpet and flowers, he recalls. “I don’t even know their names.”

But then he cautions, “If a book falls on the floor here, look carefully before you kiss it. It might be avoda zara (a book Orthodox Judaism views as heretical).”

Weinberg concurs about the need to collect anything relevant, including the sacrilegious. “We hold everything [in the NLI]. We hold Mein Kampf. The last time people burned books they didn’t agree with was in Berlin.”

The collection’s genesis began in 1965 when Scholem (1897-1982) signed an agreement bequeathing his private library to the NLI upon his death. Leshem points out many of the volumes include the scholar’s copious annotations. The philosopher and historian sometimes had his books rebound to incorporate his notes. His early comments were written with a fountain pen while more recent notes were inscribed with a ballpoint.

Leshem notes the collection has grown by 10,000 volumes since Scholem’s death. He is especially pleased that in 2017 the NLI acquired Die Heilige Schrift der Israeliten, a Hebrew Bible illustrated by Gustave Doré and edited by Ludwig Philippson that for generations had been a Scholem and Hirsch heirloom in which family births and weddings were recorded. Leshem speculates the treasure was abandoned in 1938 when Scholem’s mother Betty (née Hirsch) fled Nazi Germany for Palestine.

Himself non-observant and from a secular family, Berlin-born Gershom (Gerhardt in German) Scholem almost singlehandedly established the study of kabbalah as a university discipline. Over the course of his professional life, he published hundreds of scholarly books and articles on Jewish mysticism. While his research wielded enormous influence, many disagreed with his views.

Scholem’s friend, Prof. Saul Lieberman, who taught Talmud at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, was once asked by some students to offer a course in which they could study kabbalistic texts. He responded it was not possible, but if they wished they could have a course on the history of kabbalah. At a university, he said, “It is forbidden to have a course in nonsense. But the history of nonsense, that is scholarship.”

Asked what Scholem would do if he were miraculously to return and visit his new reading room, Weinberg shoots back, “He would take a seat and start reading.” ■