Pesach, matza, maror. Father lifts the matza, symbolizing our speedy exit from Egypt. Then, the maror (bitter herb) reminds us of the bitterness of slavery, the bondage and subjugation, so father points at… mother!

This long-forgotten custom, which apparently was never mentioned in any Rabbinical codes or books of traditional practices (yet in recent history has been discussed on the Seforim Blog), is depicted in many medieval illustrated Haggadot going back to 14th century Provence.

It is based upon Bible and Talmud (Yev 63b): “A bad woman is so terrible. ‘I have found a woman to be worse (mar) than death’ (Ecclesiastes 7:26)”.

Since antiquity, lettuce was used at the Passover Seder as maror, the bitter herb. The Talmud, already bothered by the fact that lettuce is not bitter, says that it is sweet at first, when young, when normally consumed, but at the end of its growth, as the leaves wither, lettuce becomes extremely bitter, just like our servitude in Egypt was sweet when Joseph and his brothers arrived and only became bitter under the new Pharaoh (Jerusalem Talmud, Pesahim 2:5). So too, the medieval custom hints that at first a woman is sweet, during the courting period, but eventually, after years of marriage, she becomes bitter, mar, “worse than death”.

In the 15th century, the custom spread to Germany and Italy, where it was depicted in several illustrated Haggadot, for example:

By that time, many Ashkenazi Jewish communities had begun to replace lettuce with horseradish as maror (Yiddish: Khrain; German: Meerrettich). This transition is shrouded in mystery. In the Mishna, something called “tamkha” is listed as one of the plant species that can be used for maror. Based upon Arthur Schaeffer’s research, I propose that Rabbi Meir ha-Cohen (author of Hagahot Maimoniot and a disciple of Rabbi Meir of Rothenburg, c. 1215-1293) identified “tamkha” as horseradish because “meer” sounds like the Hebrew word “mar” (bitter) and the first syllable of the French/Italian marubia (horehound, which is the identification of Rashi, as well as an opinion in the Arukh, the important medieval dictionary of Talmudic and Midrashic words). Marubia itself was possibly selected because it also sounds like the Hebrew mar (or vice-versa, the vernacular name following the Hebrew).

In addition to the phonetic similarity between the Old French and the German, there are also physical characteristics shared by horehound and horseradish, especially small white flowers:

Interestingly, at first, the bitter leaves of the horseradish plant were used for maror, not the sharp roots.

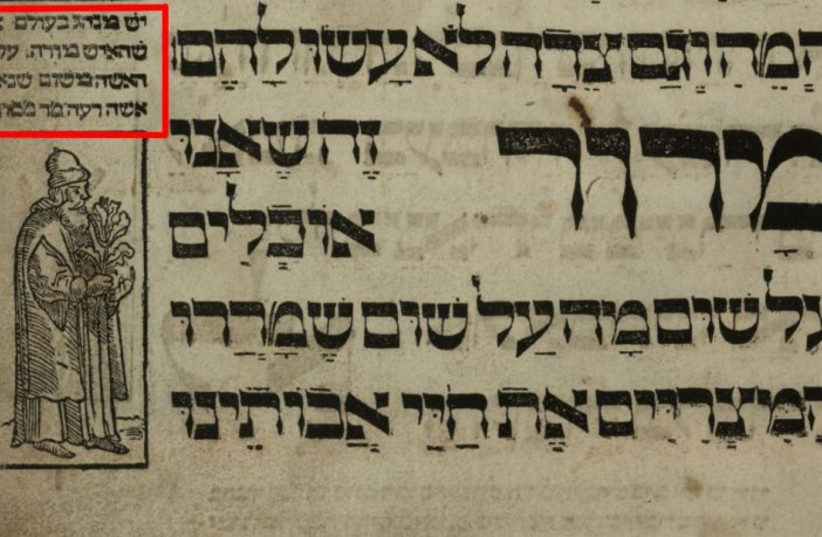

One can only imagine that Jewish women did not take kindly to the “bitter wife” custom, and we find that they ultimately struck back at the men with literary flair as sharp as the horseradish itself. This is attested to in the late 15th century Hileq and Bileq Haggadah.

The wife responds to her husband’s pointing in kind, pointing back at him dominantly from the left. The knives on the table, easily available to the wife only add to her power in the scene.

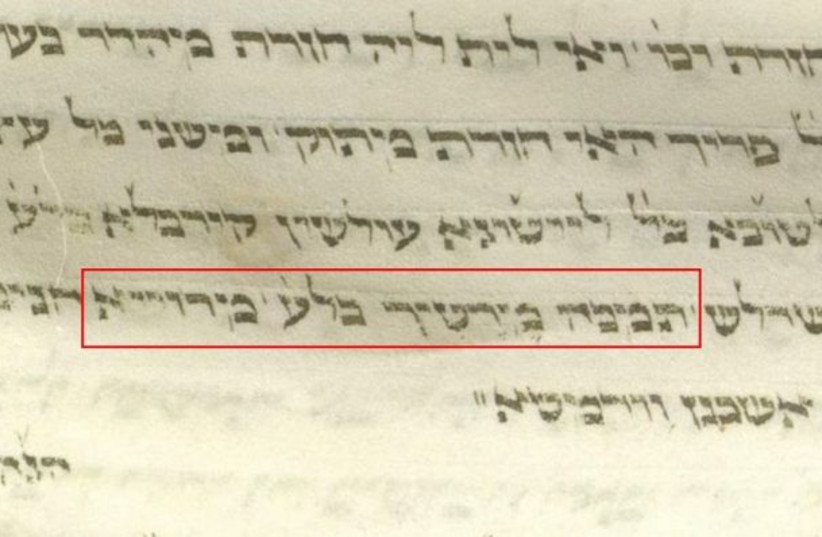

The wife’s response cleverly paraphrases the last rule of the famous 13 homiletical methods of Rabbi Ishmael, which found in Jewish prayer books and presumably familiar to the Haggadah’s readership:

“When two Biblical verses contradict each other, we require a third to decide (yakhria) between them”.

The wife poetically states that the maror will stink (yasriakh) between us, meaning that both husband and wife are equally bitter. Alternatively, she signals that it’s stink will also decide:

“That’s what you think, but I say that you are the bitter one! [How can we decide who is right?] Let’s consult a third opinion to decide between us, [the maror itself. Smell it. It stinks like you, so you must be the bitter one!]”

The men apparently began dropping the custom in the late 15th century. Perhaps they were devastated by this witty reply.

The last known description of the custom to point at the wife is found in one of the first printed illustrated Haggadot, the Prague Haggadah from 1526. Nonetheless, according to scholar Israel Peles, in that example it is simply a textual relic of an already dead custom copied from an earlier source, and the wife is not even depicted in the illustration.

In the spirit of the popular book Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus, perhaps the Passover version could be: “Men are Meerrettich, Ladies are like Lettuce”.

This article was written in memory of the author’s mother, Bruria Jacobi, of blessed memory. It appeared in English for the first time on The Librarians, the official online publication of the National Library of Israel dedicated to Jewish, Israeli, and Middle Eastern history, heritage and culture. An earlier version of the article was previously published in Új Kelet, in a Hungarian translation.