Exodus, the multitude’s sudden journey from one land to another, is once again underway.

One exodus is some 4 million Ukrainian refugees’ flight from their homeland to the outer world. Like the ancient Israelites, they grabbed whatever food they could pack, bundled what few belongings they could carry, threw last glances at their neighbors, homes and towns, and departed to a future of risk, uncertainty and loss.

As they bemoan their fate, these victims of imperialism can be inspired by the story the Jewish people will retell tonight, the biblical tale that is also about tyranny’s assault on freedom. Shaped by an autocrat who thought the people should serve the regime, and overturned by a freedom fighter’s faith and resolve, it was the first such clash in literary history.

Much more morbidly, the biblical Exodus also includes the first literary appearance of genocide, Pharaoh’s command to his people “Every boy that is born you shall throw into the Nile” (Exodus 1:22), the ancient version of bombing apartment blocks, hospitals and malls.

Yes, there is nothing inspiring in these analogies, but there is plenty of inspiration in the struggle’s dynamics – “the more they were oppressed, the more they increased” – and even more so in the story’s aftermath, in the spiritual promise of defiance, in the political prospects of dissidence, and in the military feasibility of an evil empire’s defeat; in the catharsis of “horse and driver he has hurled into the sea” (Exodus 15:1).

That, in brief, is what the biblical tells tyranny’s victims as they migrate away from Ukraine between pillars of fire and cloud.

A SECOND exodus happens daily right here, just east of Tel Aviv, south of Haifa, in the middle of Jerusalem, and all along the theoretical border between the West Bank and the Jewish state.

Pulling tens of thousands at every weekday’s crack of dawn from their beds to the Security Barrier’s checkpoints, cracks and holes, this exodus is not about the biblical tale’s political setting or violent end, but about its economic part: work.

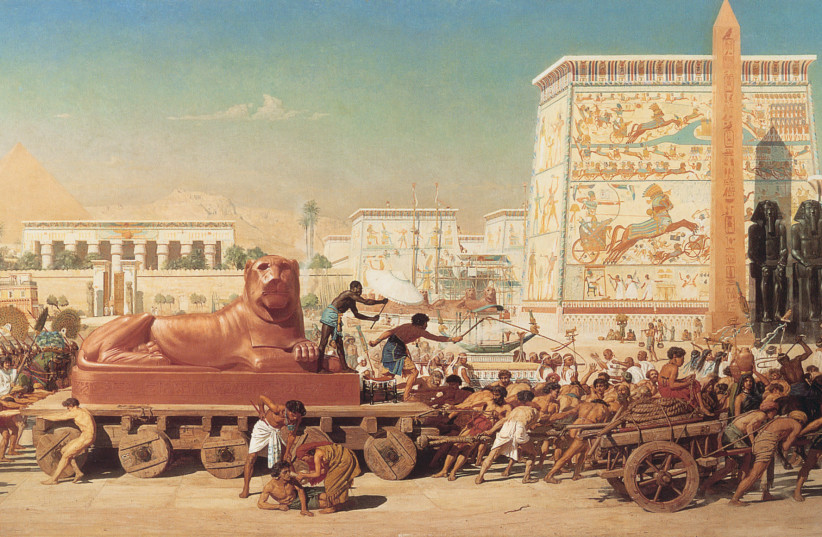

On the face of it, this daily spectacle is about slavery’s inversion; a multitude on the move not because their king is whiplashing them to build monuments, but because their leaders offer them no work at all.

At a closer look, however, this indeed is about slavery, because this multitude was robbed of the right to dignified work in their towns, and is consciously sent by its leaders to work as hewers of wood and drawers of water in their perceived enemy’s construction sites, restaurants and homes.

This daily exodus’s participants should draw two lessons from the biblical exodus: first, a government which deprives the people of their dignity is an affront not only to man but also to God; and second, dignity can be demanded even from the most evil government, and it can also be obtained.

A THIRD exodus will be visible in the coming days along the very Red Sea where Pharaoh and his horsemen drowned, as thousands of Israelis will flock to Sinai’s azure beaches, some via the newly inaugurated air route from Tel Aviv to Sharm el- Sheikh.

Yes, unlike the refugees’ exodus from Ukraine, or the workers’ exodus from the West Bank, this one is a happy tale.

Unlike our distant forebears, for whom Sinai was a transit-land at best, a punishing moonscape at worst; and unlike yesteryears’ Israelis, for whom this desert was a smoking battlefield rife with trauma, loss and grief, for today’s Israelis it is a vacation site, a lovers’ haven, and a paradise regained.

Yes, evils like the genocide and slavery that preceded the biblical Exodus can be defeated, and also altogether offset. And yet, despite the hope they can inspire, these and other analogies to the biblical exodus are flawed, both technically and substantively.

Technically, as noted by philosopher Michael Waltzer in his Exodus and Revolution (1985), an exodus is by definition a one-way journey. That is what distinguishes it from a journey like Homer’s Odyssey, a circuitous voyage whose ultimate destination is its point of origin.

The Palestinian workers arriving here daily return home every evening, and the Ukrainian refugees now flooding Poland, Germany, Romania and Moldova hope to, and will eventually, return to their land. That’s why theirs is an odyssey rather than an exodus.

Yes, many refugees don’t plan to return home. That, for instance, appears to be the case with millions of Syrians who fled to European lands. However, such choices are individual.

The biblical exodus, by contrast, was collective; a national journey designed not merely to leave one land and reach another, but to abandon the land of origin to its devices, and never return there.

In fact, as far as Moses was concerned, Egypt was to be abandoned not just psychologically, but literally and by law, as he commanded Israel’s future leaders that they “shall not… send people back to Egypt… since God warned you: ‘You must not go back that way again.’” (Deuteronomy 17:16)

And this is where the story we will celebrate tonight becomes so perplexing, especially for those of us who believe that mending the world is an ancient Jewish value, tradition and aim. It isn’t. Had Moses had such a value, he would have stayed with his people in Egypt and mended it.

Yes, Moses confronted an evil empire and also defeated it, but instead of building a new society on its ruins, he journeyed to a new land, eager to build from scratch an evil empire’s inversion; a nation of free, self-employed farmers, a nation that will limit power and check it, a nation that will demand its leaders pursue justice and obey the law.

That, in brief, is what we will celebrate tonight.

www.MiddleIsrael.net

The writer’s bestselling Mitzad Ha’ivelet Ha’yehudi (The Jewish March of Folly, Yediot Sefarim, 2019), is a revisionist history of the Jewish people’s leadership from antiquity to modernity.