Everyone needs redemption and liberty, and everyone must achieve his or her own redemption. Redemption does not come down from heaven. It is achieved by human beings who have decided that they want redemption, strive for it and achieve it.

Liberty and redemption are achieved through hard work. They are achieved through exploration. They are a lifelong project. They never end. Through liberty, man can be redeemed and achieving liberty is the final stage toward redemption.

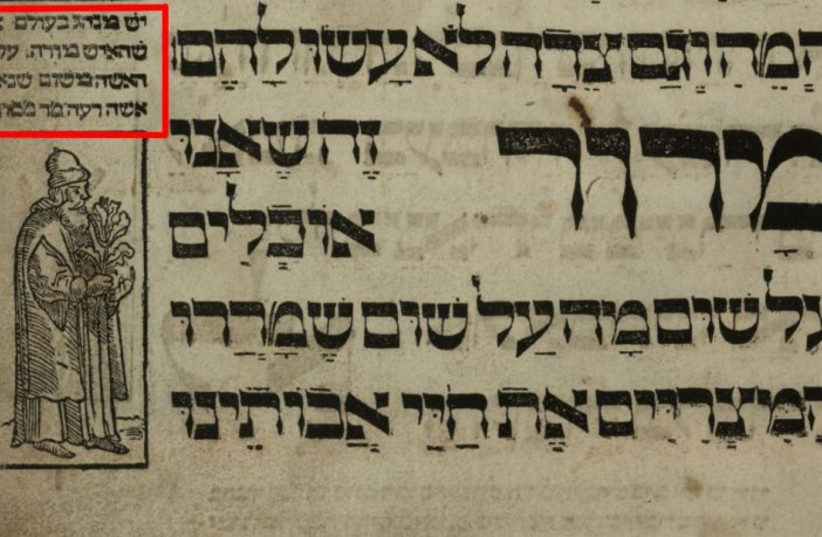

In my opinion, one of the highlights of the Seder and the Haggadah is the reading of the story of the four sons. This story has been given many verbal and artistic interpretations. While it always bothered me that the text talks about sons and not daughters, when I overcame this gender barrier, I discovered interesting strengths in this typology of the four sons. For me, the story of the four sons represents four modes of existence of liberty, especially since Passover is first and foremost a holiday of liberty and redemption. Liberty is a basic condition for redemption.

Liberty is achieved and tested in the four types through exploration carried out in the form of questions. Each of them asks a question expressing his existential state, and his conceptualization of how to achieve liberty and redemption, indicating his psychological state. The question is not merely a procedural technical approach, but rather a means of indicating and defining the essence of each of the four types.

The wise son represents proactive liberty, the wicked son represents instrumental liberty, the simple son represents passive liberty, and the son who does not know how to ask represents detached liberty, which is an indifferent attitude toward liberty in practice.

The wise son represents the type who seeks the laws and testimonies and the judgments: “What are the testimonies and the laws and the judgments that the Lord our God has commanded you?” (Deuteronomy 6:20) the Haggadah tells us is his question.

The wise son represents the absolute cosmic order. He understands that in order to be a free man, he must study the laws and testimonies and the judgments because there is no liberty save what is engraved on the tablets. The wise son’s question concerns the question of setting boundaries.

And in order to delimit him within specific real boundaries, he is symbolically told that it is forbidden to have any other food after the afikomen (Mishnah, Tractate Pesachim, Chapter 10, Mishnah 8). In other words, the afikomen is a kind of sign or symbolic boundary in the sense that the sky is the limit.

The wicked son represents the opportunist who uses knowledge and choices as an instrument for achieving selfish goals. Therefore, he also separates himself from any responsibility for others: “What do ye mean by this service?” (Exodus 12:26) – “ye and not he.” And since he has dissociated himself from the workers and laborers and is exploiting and using liberty instrumentally, he is actually a heretic. His liberty is damaged and is unlikely to lead to redemption, which is a pure and ideal state devoid of opportunism or dissociation.

The innocent son does not understand why one should study at all and strive to achieve liberty. He does “what is necessary” without asking or delving deeply – this is a psychological condition that the psychologist Erik Erikson called foreclosure. His question at the Seder is: “What is this?” (Exodus 13:14). He has no need to hurry, nothing is urgent... If it works out, that’s good, and if it doesn’t, that’s also good.

And the son who does not know how to ask is detached from both knowledge and question. He is alienated from the need for hard work. He is in a state that Erikson calls identity diffusion and does not do what Erickson calls “identity work.” Moreover, he does not seek liberty and redemption because he lives a life of inertia, and such a life is devoid of any search for meaning and liberty.

His life is conducted in the here and now, and this is what the Haggadah says about him: “You shall open for him. You shall tell your son on that day, ‘It is because of what the Lord did for me when I came out of Egypt.’” (Exodus 13:8). The responsible adult must accept responsibility for his knowledge and his liberty, and through correct mediation, must lead him to the world of knowledge that will build a world of freedom and redemption for him.

The four sons are four modes. As adults, we must provide an educational response to each according to his own needs. They are also four stages in human existence that indicate a developmental sequence whose message is that one can always advance toward liberty, and one must be aware of redemption and aspire to achieve it, but these issues can also apply to women.

In my opinion, and based on the criteria of the story in the Haggadah, the wise daughter is Nechama Leibowitz, who was a trailblazer. We are currently marking 25 years since her death. Nechama Leibowitz is considered one of the greatest Torah commentators of the 20th century. What characterized her commentary was that she asked poignant questions about the traditional commentators of the Torah, in an attempt to understand the greatest thinkers, such as Rashi and Rambam (Maimonides). And then she bravely confronted them as equals. The question was her basis for liberty and releasing the text from the shackles of convention and banality towards a deeper and multi-layered preoccupation, leading to substantive questions about human nature and the universe. Although she did not consider herself a feminist, her actual activity was purely feminist, since she shattered the traditional male hierarchy and displayed leadership in the halls of the Jewish canonical text. Nechama Leibowitz dared to open the Jewish bookcase, challenge it and conquer it.

Men and women came to study with her, waited to hear her words, and as they themselves said and I heard with my own ears, they were even afraid of her. They had an extraordinary reverence for her – for her great proficiency, her wisdom, and the liberty that she took upon herself to open up each and every verse in the Torah and each and every commentary and make it more demanding.

Nechama Leibowitz challenged the interpretive discourse because she dared to make it more difficult, to challenge it and boldly ask fundamental, difficult and sometimes embarrassing questions that shake the very foundations of conventional commentary. It should be noted that she did not seek to defy or harm but rather to know, out of reverence and responsibility for the written word and a sincere pursuit of the truth. Those who knew her used to say that her reverence preceded her wisdom.

Important Orthodox rabbis such as the late Rabbi Rafael Posen, Rabbi Yaakov Ariel, Rabbi Menachem Burstein and others explicitly referred to her in public as “my teacher Nechama.” They were proud to be among her students. People related how she would answer somewhat angrily to those who did not ask properly or who asked idle questions stemming from ignorance or inattention. Her commitment to the text was absolute, and she conducted herself in the Temple of Biblical Knowledge like a high priest. One word is written on her grave: Teacher. And this one word encompasses her essence, calling, purpose and lifelong mission.

On Seder night, against the four glasses of male redemption, I propose to drink glasses to honor the women who brought liberty and redemption to the Jewish world. Two years ago, I proposed drinking a glass of water in memory of Miriam, the sister of Moses, in memory of Miriam’s well. This year I will drink another glass of water in honor of the liberty and redemption that Nechama Leibowitz brought to us, and there is no water but the Torah. Nechama filled the water wells of the Torah. She paved the way for everyone and created redemption.

As I have written, redemption does come down from heaven. It is achieved through hard work, and is what Nechama demonstrated to us. And on an evening when the entire Jewish world is deliberating the question of what liberty is and what redemption is, I will mention the greatest of all the female commentators who dared to ask subversive questions that led her and us to liberty and redemption. She is a lodestone for the entire Orthodox, haredi, Reform and Conservative Jewish world.

Nechama Leibowitz redeemed traditional commentary. We have needed 25 years to come to terms with her absence. On Seder night, we will celebrate the victory of the spirit, the courage of the soul, and the spiritual exodus from Egypt as an ongoing process of exploration. And we will search for the Nechama Leibowitz of the next generation.

Happy Passover! And may we all enjoy good health, liberty and redemption, and have a happy holiday!

The writer holds the UNESCO Chair in Education for Values, Tolerance & Peace in the Faculty of Education at Bar-Ilan University.