The period of the counting of the Omer is meant to be a time of mourning.

While it is not as acute as the Nine Days, some of the practices familiar from the period known as the Three Weeks, including restrictions of public celebration, live music and shaving or hair-cutting are in place for almost four weeks. However, the reasons behind these mourning rites can feel more obscure than the fall of Jerusalem and destruction of the Temple.

What are we meant to commemorate and how does it contribute to spiritual growth between Passover and Shavuot? The standard answer given is usually that 24,000 students of Rabbi Akiva died at this period of time. We will look more carefully at this story below, however it is undisputed in rabbinic tradition that they all died because of misconduct toward one another.

In parallel, at this time of year, we read the Torah portion of Kedoshim, which opens with the mandate to be kadosh, or holy, “for I the Lord your God am holy.” This verse becomes a springboard for the famous difference in interpretation regarding the definition of holiness between medieval commentaries Rashi and Nahmanides.

Rashi explains kedusha (holiness) as the sum total of discipline in one’s sexual behavior. “Wherever one finds a fence around sexual prohibitions, one finds holiness.” Admittedly, when I was younger I thought it was much too narrow a definition, reducing holiness to one particular type of behavior. The concept of kedusha, was to my mind about seeking out God’s presence in the world beyond the sexual. Yet with age I have come to recognize the depth and insight in Rashi’s explanation. Looking around at the far too frequent reports of sexual misconduct within our communities, it is hard to ignore how insightful he was in understanding that there can only be Godliness when there are first and foremost perhaps, boundaries in sexual behavior.

Nahmanides in contrast, goes in a much broader direction that has more spiritual resonance with regard to our religious lives. Kedusha is not simply the performing of mitzvot. He acknowledges that the most religious of people can be degenerate within the realm of permissible Torah-mandated behavior. This is an incredible suggestion. In other words, a person can be keeping mitzvot and avoiding transgression, yet, they are degenerate while keeping Torah!

Eugene Korn in his book To Be a Holy People builds on the approach of Nahmanides when he writes: “Nahmanides understood our status as a holy people to be dependent on our doing what is morally right and good.” He notes that the Torah itself links holiness to interpersonal relations since the chapter in which holiness is commanded includes 18 out of 21 mitzvot that are ethical and demand fairness, concern and sensitivity toward the other. Korn puts forth the idea that “Jewish religion, ethics and culture cannot be reduced to law and that Jewish ethics and religion are incomprehensible in isolation from each other. Jewish ethics and religions must be inextricably intertwined if we are to aspire to be a holy people.”

This is well illustrated by a more careful look at the Rabbi Akiva story and its clear moral message toward those who live within the world of Torah. One of the 18 interpersonal mitzvot found in the holiness chapter is that “you shall love your neighbor as yourself,” followed by “I am the Lord.” According to Rabbi Akiva, this mitzvah is a major principle in the Torah.

This makes it all the more puzzling that the students of Rabbi Akiva died because they did not give honor to one another in clear defiance of this mitzvah. It is further striking that the number of dead disciples is identical to the number that die in a Divinely sent plague in the aftermath of Baal Peor in the book of Numbers.

The number is hardly accidental. Both essentially die by the hand of God rather than from an external enemy. In the earlier story, the Children of Israel die because they went astray, worshiping idols and engaging in sexual promiscuity. In the Rabbi Akiva story, his disciples sit all day and study Torah and yet are unable to give honor to one another.

This behavior is an antithesis to the type of holiness mandated by Nahmanides. In essence, their behavior is comparable to the grievous sins of idolatry and promiscuity. They may be in fact strictly following the letter of the law but this is not the kind of righteousness that pleases God.

The Netziv in his commentary states outright that God does not suffer the tzadikim, or righteous people, who do not walk in an upright manner in the ways of the world. As an example, he describes those who harbor baseless hatred in their hearts toward those they brand as heretics for not following their opinions with regard to what it means to fear God. “Even though [this behavior] is for the sake of heaven, this crookedness causes destruction of the creation and the shattering of civilization.”

The story of Rabbi Akiva’s students is not about external destruction. It is about baseless hatred that leads to arrogance, self-righteousness and finger-pointing within our communities of Torah rather than violence inflicted upon us by our enemies from without.

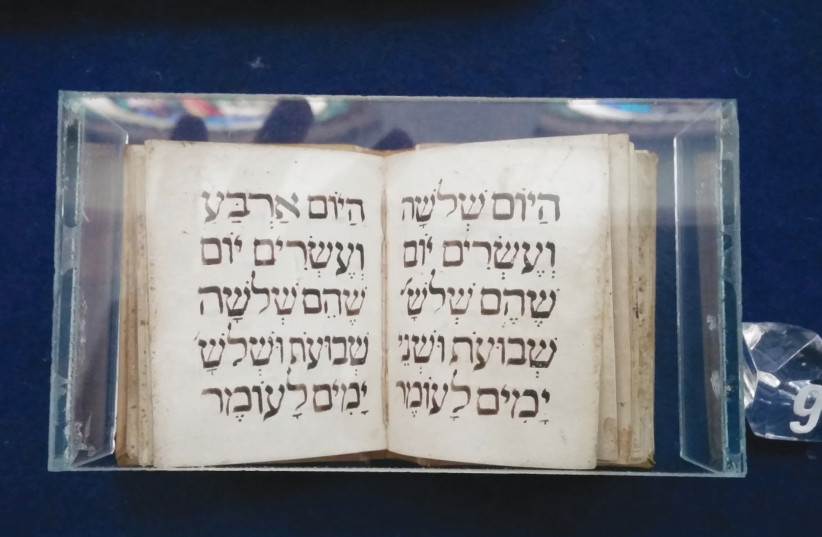

This period of time, which spans the seven weeks between Passover and Shavuot, is a time of preparation to receive the Torah. We would do well to take this time to internally reflect on what it means to synthesize our relationship with God into our relationship with the people around us.

Only then can we hope to strive for the holiness that will make us worthy to stand again at Sinai. ■

The writer teaches contemporary Halacha at the Matan Advanced Talmud Institute. She also teaches Talmud at Pardes along with courses on Sexuality and Sanctity in the Jewish tradition.