More than 40 years ago, Orson Welles, the legendary actor and filmmaker, in an iconic TV commercial, intoned in his distinctive baritone, “Some things can’t be rushed – good music and good wine.” Welles then concluded the ad for Paul Masson wines with the famous slogan, “We will sell no wine before its time.”

Though a bit far afield, similar thoughts about the passage of time ran through this writer’s mind when considering the Talmudic Encyclopedia, known in Hebrew as Encyclopedia Talmudit.

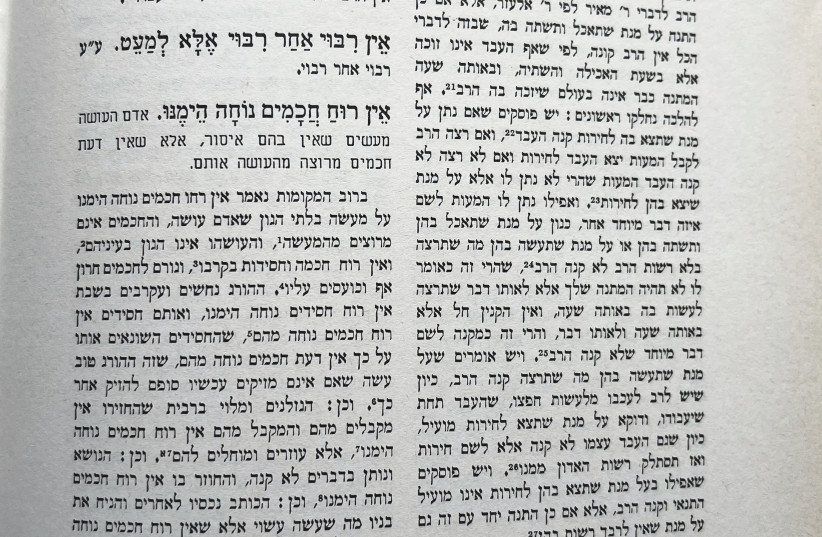

Initiated by Rabbi Meir Bar-Ilan (1880-1949), the Talmudic Encyclopedia was developed with the goal of summarizing the major halachic subjects discussed in the Talmud and post-Talmudic rabbinic literature from the Gaonic period to the present day. The first volume was released in 1947, and over the years, 47 additional volumes have been published.

In December, the 48th volume of the Talmudic Encyclopedia was issued, and the editors have now reached the Hebrew letter “mem.” The issuing of this volume was marked by a special celebration celebrating the 75th anniversary of the project at the official residence of Isaac Herzog – who in addition to currently serving as president is the grandson of Rabbi Yitzhak Halevi Herzog, the first chief rabbi of the State of Israel and a supporter of the project at its outset.

The Talmudic Encyclopedia, with its distinctive yellow cover and green design accents, has long been a staple on the bookshelves of Jewish homes, yeshivot and institutions of higher learning. Yet, what has taken so long? Did the editors anticipate that the project would still be ongoing 75 years after the first volume was released?

What's taking so long?

“THEY DIDN’T expect that it would take so long,” says Rabbi Prof. Avraham Steinberg, MD, who became the head of the editorial board of the Talmudic Encyclopedia in 2006. Steinberg, a distinguished pediatric neurologist, has written extensively on Jewish law and medical ethics and authored the seven-volume Hebrew-language Encyclopedia Hilchatit Refuit, which was translated into English by Prof. Fred Rosner, as the Encyclopedia of Jewish Medical Ethics.

In a Zoom interview with The Jerusalem Post, Steinberg outlined the history of the Talmudic Encyclopedia, the reasons for the delays, and the project’s current status.

Bar-Ilan was the son of Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehuda Berlin, known as the Netziv, who headed the Volozhin Yeshiva from 1854 until its closure in 1892. Bar-Ilan studied at the University of Berlin and later became a leader in the Mizrachi movement. He came to the United States in 1913 and moved to Israel in 1923.

In 1942, when Bar-Ilan learned about the Holocaust, he was concerned not only for the well-being of the Jewish people but for the preservation of the Torah.

“Since the center of Torah study was in Europe,” says Steinberg, “he was afraid that the Torah would become lost. He felt that the rabbis in Israel who were still safe should do something to preserve the Torah.”

Bar-Ilan suggested the creation of a reference work that would contain an alphabetical listing of the main topics in Jewish law, with brief articles summarizing the background and sources of each entry.

He enlisted Rabbi Shlomo Yosef Zevin, one of the leading Torah scholars of the day, to assist in the preparatory work for the encyclopedia.

“It was a very good choice,” says Steinberg, “because Rabbi Zevin was not only a genius but had the ability to write clearly, concisely and accurately.”

Zevin spent several years preparing a list of 2,500 entries for the nascent project and determined the style and substance of the entries.

“The language of the encyclopedia is Hebrew,” says Steinberg, “but it is not biblical Hebrew, nor is it Mishnaic Hebrew, nor is it modern Hebrew. It is a type of Hebrew that encompasses all of these, but in a unique style.”

“The language of the encyclopedia is Hebrew, but it is not biblical Hebrew, nor is it Mishnaic Hebrew, nor is it modern Hebrew. It is a type of Hebrew that encompasses all of these, but in a unique style.”

Rabbi Prof. Avraham Steinberg

Most importantly, he adds, virtually every sentence in the Talmudic Encyclopedia has a footnote indicating the source for the statement.

For example, the Hebrew entry for mourning, or aveilut, begins by stating that the practice was observed in biblical times, quoting the verse in Genesis that mentions that Joseph mourned for seven days after the death of his father, Jacob. That sentence ends with a footnote, directing readers to the relevant verse in Genesis.

The following sentence in the entry notes that some authorities use this verse to prove that the seven-day mourning period is of biblical origin. That sentence has footnotes listing a supporting passage from the Jerusalem Talmud and the 10th-century commentary of Rabbi Isaac Alfasi, who lived in Morocco.

The first volume of the Talmudic Encyclopedia was published in 1947, and, says Steinberg, the original goal was to finish the project in 16 years.

Steinberg explains that Bar-Ilan wanted to keep the entries concise. “His idea was to keep it as simple as possible – to include the major references.”

The first two volumes were written in that style, but after Bar-Ilan’s death, Zevin expanded the length of the articles.

“For me,” says Steinberg, referring to the writing style that Zevin employed, “this is the prototype of how an entry should be written. It includes a great deal, but not necessarily every single reference.”

After Zevin’s death in 1978, Rabbi Raphael Shmuelevitz (1938-2016), the head of the Mir Yeshiva in Jerusalem, became the chief editor. Shmuelevitz, says Steinberg, decided that entries in the Talmudic Encyclopedia needed to include as many references as possible. This slowed down the process and, Steinberg says, turned many articles into almost book-length pieces rather than summaries of a subject.

When Steinberg became head of the project, he wanted to return to the more concise style. Articles are now being written more in line with Zevin’s style and are shorter than they used to be.

Despite the shorter articles, says Steinberg, the writing process was still taking quite a while and was nowhere near being finished.

SIX YEARS ago, well-known Toronto philanthropists Dr. Dov Friedberg and his wife, Nancy, approached Steinberg, offering to provide financial assistance to complete the project. Friedberg had assumed that the entries had already been written and offered to provide the money for the printing of the remaining volumes.

Steinberg explained to Friedberg that of the original 2,500 entries prepared by Zevin in the 1940s, 900 entries were still remaining that had not been completed. The writing process that editors and writers were using was labor-intensive and was taking far too much time.

“In the old days,” he says, “there was a small group of people writing. After the article was written, the author would send it to a reviewer. It could take a long time to write an entry. The reviewer would go over everything from the beginning and write his comments, but by then the writer was in a different world.”

Steinberg changed the system. He took his most talented editor, with 30 years of experience, who trained a new group of applicants to write entries. “We had 100 people going through this school, and 20 were accepted.”

Moshe Schapiro, CEO of Yedidut Toronto, the Israeli arm of the Friedberg Charitable Foundation, says that the previous editorial environment at the Talmudic Encyclopedia was a more yeshiva-style environment which had to be modified into more of an assembly-line process. “It was an important transformation that we were able to make, like a beit midrash that became a factory.”

“It was an important transformation that we were able to make, like a beit midrash that became a factory.”

Moshe Schapiro

In order to accelerate the work, four writing groups were set up. Each group is assigned an editor, and rather than wait until the entry is completed before giving it to the editor, the writers work in parallel with the editors. The reviewer goes over the article as it is written.

“We can write much faster than before but at the same level of quality,” says Steinberg.

The Friedberg family donated a substantial amount of financial assistance to Yad Harav Herzog, the publisher of the Talmudic Encyclopedia. The assistance was provided with two conditions, says Steinberg. The first condition was that the writing of the entries had to be completed within 10 years.

“We are now six-and-a-half years into the 10 years, and we must finish the project by 2024,” he says. The second condition was that while the Friedberg family would provide the bulk of the funding, Yad Harav Herzog would be responsible for raising between 60% and 65% of the necessary amount to complete the project.

Together with Yedidut Toronto, Yad Harav Herzog wrote a business plan.

“We calculated that 900 entries out of the original 2,500 were left to write, leaving roughly 100 entries per year to finish,” says Steinberg.

Every six months, Yad Harav Herzog submits entries and the budget to show that they have generated the requisite amount of money needed and have sufficient funds to continue.

THE FRIEDBERG family is no stranger to the world of computerized Hebrew text projects. The Friedberg Genizah Project digitized the entire corpus of manuscripts discovered in the Cairo Genizah, a collection of over 200,000 fragmented Jewish texts, many of which were stored in the loft of the Ben Sira Synagogue in Cairo. The Genizah project photographed all the text fragments, put them online, and put together tools to identify fragments of manuscripts and piece them together.

“For the first time since the eighth century, “says Schapiro, “people can see the entire gamut of the collection in a legible way that is available to scholars all over the world. The Friedberg approach to these kinds of literature programs is like that. We are attracted to game-changing situations.”

Yad Harav Herzog is on schedule to complete the writing of the Talmudic Encyclopedia by 2024, says Steinberg. By the time the project is completed, the encyclopedia will be close to 80 volumes. Yad Harav Herzog is also planning a complete online version, which will contain all of the text of the volumes.

The current printed text of the Talmudic Encyclopedia is available on Bar-Ilan University’s Responsa Jewish Library CD, and newer entries can be read online at the wikiyeshiva site.

Steinberg tells a humorous anecdote about the length of time it has taken to complete the project.

“One of the last alphabetical entries in the encyclopedia,” he says, “will be for Tisha Be’av, the fast day commemorating the destruction of the Temple, which begins with the Hebrew letters tav and shin, which are among the last letters of the Hebrew alphabet.”

Citing the ancient tradition that states that when the Messiah arrives, Tisha Be’av will no longer be observed as a fast day, but will be a holiday, Steinberg says, “They realized that the text was taking them so long to complete that, supposedly, the text will say, ‘Once upon a time it was a fast day, but today it is a holiday.”

Apparently, wine and music aren’t the only things that cannot be rushed. ■