When an instructor at the new Tikvah Online Academy asked me to help clarify and formulate the Jewish perspective on the symbolic significance of the snake in Adam’s Original Sin, I was taken aback but also intrigued. He sought to know why – of all animals in the Garden of Eden – the snake was the one that tempted Adam and Eve to sin. But the way he phrased the question spoke to my interests in Hebrew etymology.

He asked about the relationship between nachash (“snake”), nechoshet (“copper”), and nichush (“divination”). All three of these Hebrew words derive from the same triliteral root (nun-chet-tav). It is not uncommon for Hebrew roots to be polysemous – that is, to have multiple meanings. But the prospect of seeking a common theme that unites these disparate ideas excited me. My interlocutor also wanted to know what makes a snake a snake. Finding a uniting thread among these three words can help shed light on what it is about “snake-ness” that set up the snake to be the instigator of the events in the Garden of Eden. So, I went to work trying to find what unites these three concepts, and I arrived at some fascinating results.

To state my findings clearly: The common denominator between nachash, nechoshet, and nichush is that they all play second fiddle to something else. In other words, they are not as important as they want you to think they are but instead represent entities or concepts that are subordinate to something else.

Unraveling subtle threads in the Garden of Eden

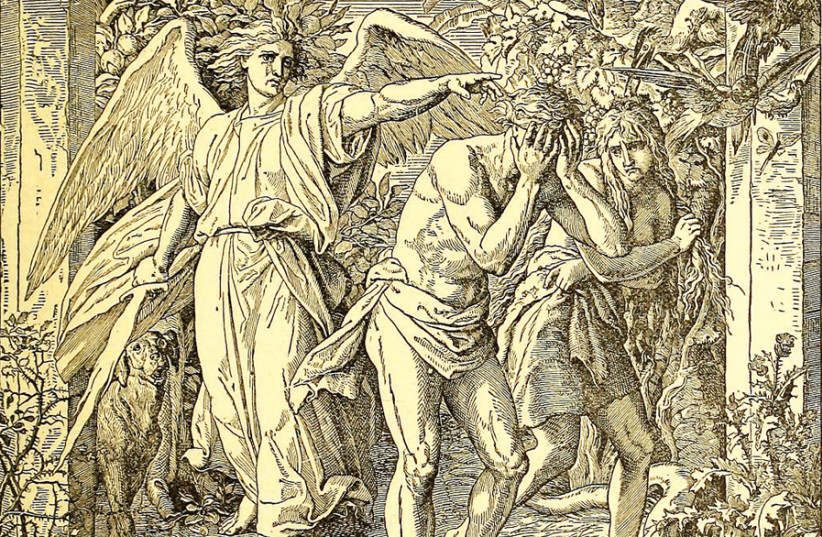

Allow me to explain by starting with a little-known midrashic passage in Pirkei DeRabbi Eliezer (ch. 13), which states that Samael (the angelic embodiment of the external evil Inclination) was riding the nachash (snake) in the Garden of Eden. We tend to think of the snake as the villain in the Garden of Eden. But this portrayal challenges the notion that the snake itself was solely responsible for Adam and Eve’s downfall. According to this midrash, the snake was just a vehicle for the furtherance of Samael’s agenda – just like we would never blame the horse for its rider’s actions. (By the way, the Zoharic literature has parallels to the midrash’s dynamic duo of Samael and the snake).

This also explains why the snake crawls on the ground and wiggles around but does not walk upright (or even just above ground level) like other, more respectable, creatures do. The snake’s lowly place and its bizarre mode of ambulation reflect the idea that the snake itself is a nobody. As we will explain, this was all part of the snake’s “punishment” that was meant to show all and sundry the creature’s intrinsic insignificance in the great scheme of things.

The word nechoshet also fits the theme. In the hierarchy of precious metals, copper is seldom the metal of choice. Copper is a cheap everyday metal, used for pennies. It is always inferior to gold and silver. Copper is often alloyed with other metals to produce bronze. But nobody strives for a bronze medal; they want gold or silver. From a Jewish perspective, this notion of copper’s inferiority is mirrored in the construction of the Tabernacle and the Holy Temple. Most of the important ritual items in those holy places were made of gold or silver because they are the most important precious metals; copper plays only a lesser role. One example: In the instructions for constructing the Tabernacle, the outer altar was to be coated with nechoshet (Exodus 27:1–8), as opposed to the inner altar which was gold-plated (Ex. 30:15).

The terms nachash and nechoshet make another appearance in the Bible — this time alongside each other. When the Jews in the wilderness were being attacked by poisonous snakes, God told Moshe to “make a snake” (Numbers 21:8), without specifying how to make it. The next verse reveals that Moses crafted a copper snake (nachash nechoshet). This raises the question of how Moses knew which material to use. The Midrash (Gen. Rabbah §31:8) suggests that Moses derived this detail from a clever wordplay: He took the similarity between nachash and nechoshet as an indication to fashion the snake out of copper.

This copper snake, while serving as an apotropaic ritual item to heal those bitten by real snakes, was never intended to be understood as possessing any inherent power. Rather, the whole point of the copper snake was, as the Mishnah (Rosh Hashanah 3:4) states, to remind the Jews of the One Above and inspire them to connect to God. This reconnection with God would heal them from their snakebites, not the copper snake itself – which had no intrinsic power.

Moshe deduced that the snake should be made of copper because nechoshet is similar to nachash. At face value, they are similar because the words sound similar and share the same root. But they are also similar on a deeper, conceptual level. Just like the snake was actually insignificant in the Garden of Eden story (it was merely Samael’s puppet), copper is an insignificant metal. It was obvious that copper was the most appropriate material for the snake because nechoshet is a metal that isn’t important in its own right. Likewise, the copper snake did not have any inherent significance or power of its own and served merely as a means to an end (i.e., to remind the Jews of God). God Himself always remains the ultimate healer (Exodus 15:26, Deut. 32:39).

Now let us consider the third word in our group: nichush — “divination.” Nichush is a forbidden, quasi-idolatrous modality of fortunetelling. It might be somewhat effective, but it is certainly not as effective or accurate as direct messaging from God. The best way to tell the future would be to consult with a genuine prophet, or at least with the urim v’tumim in the Kohen Gadol’s (high priest) breastplate. In this way, nichush takes a backseat to better ways of fortune-telling and does not rank number one, just like nechoshet is not the number one prestigious metal and the nachash was not the main player in enticing Adam and Eve.

Balaam praised the Jewish people by stating, “For there is no nachash in [the House of] Jacob” (Numbers 23:23). In context, it is clear that Balaam meant that the Jews do not turn to diviners or other sorts of magical intermedia but instead relate directly to God. Yet the word used in this verse is nachash (snake), not nichush. However, as we explained, nachash and nichush essentially refer to the same concept — the notion of something secondary – and are thus used here interchangeably. Accordingly, when Balaam praised the Jews for not having a nachash, this means that they did not bother with secondary, less potent forms of relating to the supernatural but instead appealed directly to the One God Himself.

Let’s take all of this and relate it back into the narrative of the Original Sin. We see that although the snake seems to be the villain, it actually plays only a very small part. The snake is just Samael’s lackey and, as such, is insignificant and secondary. The goal of the evil inclination (aka Samael) was to get Adam and Eve to sin by eating the forbidden fruit. The snake was just the means to that end. Its role was to provide a persuasive argument to convince Eve to sin. Thus, the snake represents the false ideologies and twisted thinking that lead a person to evil. As Sforno (Genesis 3:1) puts it, the snake represents the imaginative faculty that leads people into thinking that they are better off sinning than not. The temptation to sin comes in many guises, wears many faces, and speaks many tongues. This is the snake, which always tries to convince us in the way that speaks to us the most. But the snake is just a smokescreen for the evil inclination. Behind all the fancy ideas and ideologies there is just one old evil inclination, with the simple goal of making us sin.

The snake was just a puppet, utterly controlled by Samael. It was, after all, an animal (even if it could talk). It did not have free will. Only that which has free will is morally culpable and can be liable for reward and punishment. As such, the snake wasn’t truly “punished.” Nonetheless, the snake needed to be subdued and put in its place. That’s why it got punished by being banished to the ground, so that we can all see its insignificance. We ascribe no prominence to a snake squirming around in the dirt, without the ability to walk upright or even on all fours like a regular animal. We should likewise look down on all the false ideas that the metaphorical snake tries to peddle on behalf of its master, the evil inclination.

This idea that the snake’s banishment to the ground serves as a symbolic act to highlight its triviality and lack of prestige adds a new layer to our understanding of its supporting role in the Original Sin narrative.

To paraphrase the Talmud (Brachot 33a) in a similar context, “The snake does not cause death; sin causes death.” A snakebite is just the divine medium for carrying out God’s master plan, but the snake itself is not at fault and is not even an important actor in the big picture. Thus, the nachash is always someone else’s pawn.

With this in mind, we can better understand the message that Moses sought to convey to Pharaoh by turning his miracle staff into a snake (Exodus 7:10). Moses’ staff, which is analogous to a king’s royal scepter, has no inherent power on its own; it is rather like a snake in that it serves a secondary role in bringing to reality the will of he who holds the staff. By relaying this lesson, Moses intended to stress that the miracles that were destined to occur in the lead-up to the Exodus will not simply reflect the elements of nature collaborating against the Egyptians (like a pagan mindset might understand those developments) but are rather reflections of a higher authority harnessing His creation to do His bidding and bring His will into reality. The staff itself did not perform the miracles; God performed the miracles through the staff. The staff itself is only a tool — precisely like a snake.

If the nachash links up with the evil inclination, it can produce an argument or ideology than is pro-sin. But if the snake is used for a holy purpose — like to help remind one about Hashem and inspire one toward the good – then it can generate an argument or ideology for the side of good. It might be taking things a bit too far to say that nachash, nechoshet, and nichush are essentially three aspects of the same idea expressed in different contexts, but they certainly reflect a common overarching theme that offers us a compelling lens through which to examine biblical narratives and themes.

In essence, the connection between nachash, nechoshet, and nichush is their shared role as secondary elements, eclipsed by something more significant. The nachash in the Garden of Eden was simply a tool for Samael, while nechoshet is likewise overshadowed by gold and silver, and nichush takes a backseat to genuine prophecy. These findings shed light on why the snake was chosen as the instrument of temptation in the Garden of Eden. The snake’s role as a mere pawn in a larger scheme underscores the vulnerability of humanity to manipulation and temptation, urging us to exercise discernment and moral judgment in the face of seductive influences. ■

Rabbi Reuven Chaim Klein is a scholar, author, and lecturer living in Beitar Illit. He can be reached via email at historyofhebrew@gmail.com. He writes an internationally syndicated weekly column about synonyms in the Hebrew language. Many of his writings and lectures are available for free online.