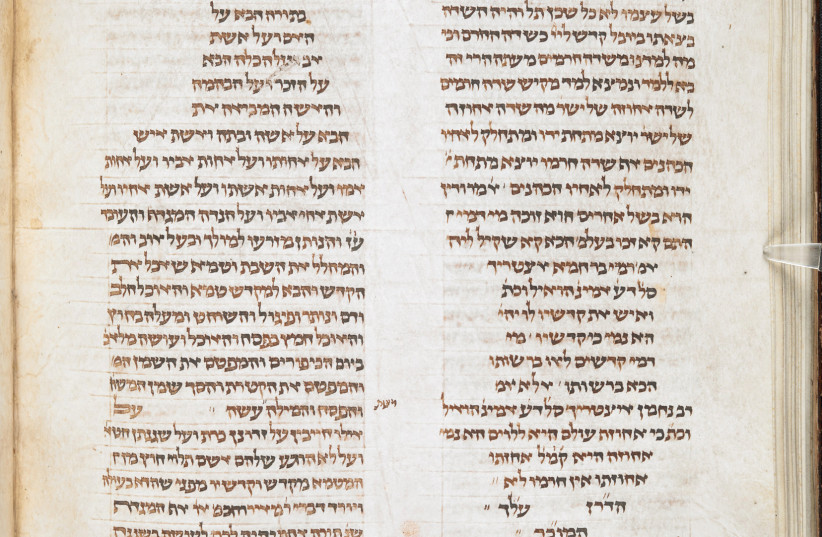

Good teachers know that telling stories is an effective way to illustrate and reinforce points they are trying to make. The Mishna and the Talmud, composed mainly of laws and religious teachings, frequently use stories about rabbis in just this way.

The Mishna opens with the opinions of three rabbis concerning the proper time to recite the Shema (“Hear, O Israel”) prayer in the evening. Immediately after that is a story about one of these rabbis. His sons came home from a party late one night and asked him whether it was too late to recite the Shema. He told them that it was not too late; his answer to them was consistent with his previously mentioned legal opinion.

But curiously, this example of the relationship between legal statements and anecdotes about Halacha (Jewish law) is not the standard one in the Babylonian Talmud. In The Stories They Tell: Halakhic Anecdotes in the Babylonian Talmud, Prof. (emerita) Judith Hauptman of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, a leading scholar of rabbinic literature, explains, “Since halachic anecdotes, the subject of this volume, appear only sporadically in the Talmud... a traditional commentary fails to note their cumulative message.”

In this volume, she has gathered most of the evidence, concluding that in most cases, the anecdotes are at odds with the halachic discussion.

One illustrative example: In the Talmud (Mo’ed Katan 27b), Rabbi Abba bar Aybo (generally known as “Rav,” early 3rd century CE) taught that when a member of the Jewish community dies, all Jews in that town are forbidden to work until the body is buried. After this legal statement, the Talmud tells the story of a student of Rav, Rabbi Himnuna, who lived a generation later.

Rabbi Himnuna visited a town and found that Jews there were ignoring the legal ruling of the master, Rav. They were at work even though a community member had died and hadn’t yet been buried. Rabbi Himnuna was upset and contemplated punishing the community. But the townspeople explained to him that they have “burial groups” in the town. (Some understand this text as the earliest source for the concept of hevra kadisha, the Jewish burial society.) The visiting rabbi accepted this justification.

Many students of Talmud studying this passage would simply put the legal text and the anecdote together and summarize: “If a Jewish community has a burial society to which they have delegated responsibility, other people can go to work before a deceased community member is buried. Otherwise, no one should go to work before the burial.”

BUT HAUPTMAN argues that a proper reading of this text involves sensitivity to halachic change over time. In her reconstruction, at the beginning of the 3rd century, “there is no reason to think that Rav, when issuing his rule, was... allowing people in a town with ‘burial societies’ to continue to perform labor.” Either other rabbis later relaxed Rav’s strict standard, or else the Jewish community adopted more lenient standards even without rabbinic sanction.

After analyzing a series of texts where one rabbi happened to visit (iqla in Aramaic) some location, she concludes: “The initial assumption of many, even most, rabbinic researchers is that halachic anecdotes, of which iqla anecdotes are a subset, are reports of how an amora [a Talmudic rabbi] carried out a Halacha and nothing more.

“I argue that a plain sense reading of the anecdotes shows that they play a key role in the development of Halacha. [In] most iqla anecdotes... the end result is modification of Halacha, usually in the direction of leniency.”

The cumulative evidence is strong. Hauptman walks us through around 80 halachic anecdotes (of the iqla variety and six other categories) in the Talmud. She does an admirable job of explaining halachic issues in non-specialized English. Nevertheless, many of these anecdotes deal with obscure minutiae of Halacha that might be hard for non-specialists to appreciate.

The Talmud, edited around 1,500 years ago, contains rabbinic statements, discussions, and anecdotes from over three centuries. Is Hauptman arguing that the editors of the Talmud were purposely embedding into the Talmud the message that Jewish law develops over time in the direction of leniency – a message that most students of the Talmud have not picked up on in the past? Or is she claiming that by doing historical sleuth work, we can see a message that the Talmud’s editors were not consciously promoting?

Either way, this volume presents a novel way of reading Talmudic anecdotes and offers an interesting thesis that already in the days of the Talmud, change toward leniency over time was inherent in the rabbinic system.

The writer is professor emeritus at York University and lives in Jerusalem.

The Stories They Tell: Halakhic Anecdotes in the Babylonian Talmud

By Judith Hauptman

Gorgias Press

326 pages; $55