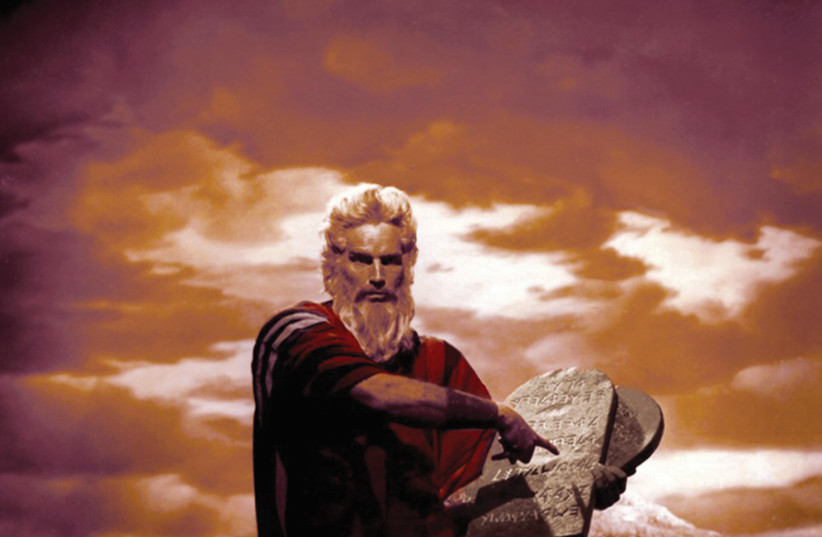

Cecil B. DeMille set the standard for biblical epics. The Ten Commandments, made in 1956, was one of the most spectacular epics ever filmed. It runs three hours and 40 minutes and earned more than $65 m. upon release. DeMille used 14,000 extras and 15,000 animals! The special effects, such as the parting of the Red Sea and the revelation at Mount Sinai, are breathtaking, even today.

The acting is also epic, way over the top, with Charlton Heston’s Moses and Yul Brenner’s Pharaoh chewing up the lavish scenery. (There is the unforgettable “Moses! Moses!” exclaimed by Nefritiri, played by Anne Baxter, as Moses rejects his Egyptian family to liberate his suffering people.)

The Torah tells of two sets of the Ten Commandments. Moses got a second set after he shattered the first set because of the sin of the Golden Calf. The 1956 film was DeMille’s second version of The Ten Commandments. The first was a silent film made in 1923. (He also made The King of Kings, a silent version of the Christian gospels, in 1927.)

What was the 1923 version of The Ten Commandments?

The 1923 version is very different from the 1956 film. It is, essentially, two separate films. The first half of the film is situated in ancient Egypt. The opening scenes depict the hardship of the Hebrew enslavement, the Ten Plagues, the Exodus and the splitting of the Sea.

The second half of the film introduces us to a family with two sons. One son, John, is loyal to his devout widowed mother and is in love with his childhood sweetheart. His brother, Dan, is selfish and ambitious.

Dan steals his brother’s girlfriend and engages in shady business practices that result in death. He gleefully violates every one of the Ten Commandments. DeMille was a real moralist, and the evil brother is duly punished for his sinful ways, while the righteous brother is rewarded (he gets the girl in the end).

This film was also characterized by special effects way ahead of its time. DeMille built huge lavish sets and used massive amounts of water to film the splitting of the sea. Like the 1956 version, DeMille dances on the fine line between the vulgar and the sacred in the Golden Calf orgy scenes. He piously wants to portray the depravity of the sinners but seems to have an awfully good time doing so.

The silent version also has its share of camp. John, for example, warns his wayward brother (in an intertitle text), “Laugh at the Ten Commandments all you want, Dan, but they pack an awful wallop!” Dan later counters, “I told you I’d break the Ten Commandments, and look what I’ve got for it – success! That’s all that counts! I’m sorry if your God doesn’t like it – but this is my party, not His!”

Critics praised the biblical half of the film but were more critical of the “modern story” for its cliché storytelling and wooden dialogue.

But it really is a film about the Ten Commandments.

What was the 1956 version of The Ten Commandments?

THE 1956 version is different.

It is an appropriate film for Passover because it is mostly about the Exodus from Egypt. Only the very last part of the film depicts the revelation at Sinai and doesn’t relate to its contents at all. In one major way, it is not appropriate; the Haggadah used in the traditional Seder goes out of its way to avoid mentioning Moses (the rabbis wanted to emphasize the divine role and minimize the human role in the Exodus from Egypt).

As DeMille says in a remarkable monologue that opens the film: “Ladies and gentlemen, young and old, this may seem an unusual procedure – speaking to you before the picture begins, but we have an unusual subject. The story of the birth of freedom. The story of Moses.”

For DeMille, the story of the Exodus is the story of Moses. The film tries to faithfully follow the opening chapters of the book of Exodus, from the birth of Moses through the splitting of the Red Sea. At the Revelation at Sinai, according to most sources, it is Heston’s voice used when God speaks (some say it is DeMille’s voice).

Since the first 30 years of Moses’s life are not described in the Bible, DeMille consulted with religious leaders, including rabbis, in making the film. He turned to the ancient historian Josephus, as well as Philo. He relied heavily on midrash, the rabbinic interpretation of Hebrew scriptures, to fill in the story. In that way, it is a Jewish film. He also consulted with Christian and Muslim scholars.

In other ways, all of DeMille’s ambivalence about his own Jewish background is apparent. DeMille’s mother, Beatrice Samuel, was a Jewish girl whose family emigrated from Liverpool. She converted to marry Henry, her Methodist preacher/theatrical entrepreneur fiancé. Her father was vehemently opposed to the marriage.

DeMille never denied his Jewish roots, but he was a devout Episcopalian Christian in his own idiosyncratic way. He attended church regularly, and the daily shoots for his biblical films opened and closed with scriptural readings and prayers. He was married to Constance his whole adult life and was deeply devoted to her. However, he was a flagrant philanderer, with one mistress after another.

HOLLYWOOD HAD plenty of Jewish actors, yet there are no Jews in any leading roles in The Ten Commandments. Heston is Moses; Martha Scott is Yocheved; John Carradine is Aaron; Olive Deering is Miriam; John Derek is Joshua (whom DeMille loathed because he didn’t know anything about the Bible); Yvonne De Carlo plays Zipporah, Moses’s Midianite wife.

The most prominent Jew in the film is the wonderful Edward G. Robinson. Yet, he plays an evil Israelite, Dothan. Robinson was a very proud Jew. He had been gray-listed for his liberal politics during the Hollywood blacklist, which DeMille championed. Robinson remained grateful to DeMille for the rest of his life for casting him in The Ten Commandments and thus restoring his career in Hollywood.

Many Jewish actors are in minor roles. Herb Alpert (of the musical band Tijuana Brass) plays a drummer in the golden calf scene. Joanna Merlin plays one of Jethro’s daughters; she went on to originate the role of Tzeitel in Fiddler on the Roof.

Accusations of antisemitism were also leveled against DeMille, starting with the 1927 release of his Christian epic The King of Kings. DeMille screened the film for numerous religious leaders before its release, including his friend Rabbi Edgar Magnin. Many Jewish leaders were disturbed by the way Jews were presented in the film. They felt that it perpetuated the libel that the Jews were responsible for the crucifixion of Jesus, implying collective Jewish guilt. DeMille was sensitive to these charges and rewrote the scene with Pontius Pilate numerous times.

DeMille became increasingly conservative as he got older, and was one of the most enthusiastic supporters of the anti-Communist investigations of the House Un-American Activities Committee.

When Joseph Mankiewicz was nominated to be head of the left-leaning Screenwriters Guild, DeMille refused to support his candidacy. There are reports that before the vote, he spoke of unwanted “foreign” influences in Hollywood, mentioning only Jews. There are conflicting reports about this incident, and no written record exists.

THE TEN COMMANDMENTS changed DeMille’s life in many ways, especially his decision to film on location in Egypt. His adopted daughter Katherine married an Egyptian polo player.

The film literally killed DeMille. He suffered a massive heart attack climbing Mount Sinai and never fully recovered. He never directed another film and died in 1959.

This year I suggest that we heed the words that DeMille used to open the film at our own Seders. Almost 75 years later, they are remarkably prescient and captured the spirit of the Haggadah:

“Are men the property of the state or are they free souls under God? This same battle continues throughout the world today. Our intention was not to create a story but to be worthy of the divinely inspired story created 3,000 years ago: The Five Books of Moses.”

Cecil B. DeMille

“Are men the property of the state or are they free souls under God? This same battle continues throughout the world today. Our intention was not to create a story but to be worthy of the divinely inspired story created 3,000 years ago: The Five Books of Moses.”

The writer is the founding rabbi of Congregation Kol HaNeshama in Jerusalem. Over the past 10 years he has watched and cataloged more than 1,000 films from the 1950s.