In recent years, we have witnessed increasing attention paid to the deeply disturbing phenomena of sexual harassment and abuse. As pervasive a challenge as this is, it is of course not a new one, with traditional Jewish sources and halachic [according to Jewish law] responsa through the ages tackling this issue. In our analysis, the Torah approach – and the seriousness it is given – is very much in line with the modern-day response as seen in the #MeToo movement.

Sadly, no community is immune to this problem. As representatives of the religious-Zionist community, we would be failing in our roles if we were to ignore that this challenge has pervaded our midst as well. We are all familiar with numerous cases that have received high-profile attention, including individuals who were previously held to high status within the world of Jewish leadership. Yet we also know that there are likely many more cases which are not brought to light. This is either because of stigma or legitimate fear on the part of the victims over what such an association might mean.

We cannot hide from the reality that lives have been destroyed by such abusers. To do so would mean we were both failing the victims, but also failing as a Jewish community guided by Halacha and morality.

We must stress that use of unwanted sexual behavior or messaging to enforce power over another is a deeply serious transgression of Torah and halachic norms and must be condemned in the strongest terms possible.

We must also stress that our conclusions are relevant regardless of the gender of the abuser or the victim. We are also fully aware that both males and females have been the victims – as well as the instigators – of all too many attacks.

As with all aspects of halachic discourse, it is critical that we approach this issue both with the proper level of thought and restraint, and enlist historical teachings to better understand the seriousness of the situation.

With no hesitation, we can firstly establish that halacha views sexual abuse in the harshest of terms, and in our estimation, calls for severe punishments to those who abuse others.

This understanding can be extrapolated from the Torah teachings regarding rape. According to most halachic authorities, under specific circumstances, one is able to take the life of a rapist if it will mean sparing the victim of the criminal’s intended act.

The seeming justification for this ruling is predicated upon the understanding – which is supported by modern research and observations – that a victim of rape often suffers incurable emotional traumas as well as a destroyed sense of trust. This is, of course, beyond the more immediate – but no less traumatic – physical pain that such a victim is forced to endure.

BECAUSE THE intent of a sexual abuser is to impact that sense of irreparable harm and loss of the victim’s innocence, halachic authorities would be wise to look upon these acts with the same seriousness as rape – even when the sexual act has not been completed.

Certainly, we must recognize that in the realm of inappropriate sexual behavior there exists a range of severity, and it would be both intellectually and halachically dishonest to put all on the same plane as rape.

We must also relate to “less serious” acts of abuse, like when a person forces a victim to undress against his or her will, or where a perpetrator initiates unwanted physical contact with the victim.

Some might look to mitigate or even defend these actions by arguing that they cannot be judged with the same perspective as rape because the sexual act was not the intended goal.

But our outlook on these issues cannot be solely swayed by the end result, and we must again appreciate that the intent of the abuser is to impact immense emotional pain with little regard for the long-term damage that will result.

We can also observe that humility, privacy and modesty – embodied within the term tzniut – are ideals that are not only halachic concepts but moral ones.

Tzniut – often translated at “modesty” – is a concept that is placed at the very heart of all interpersonal relationships. For that reason, even in the most intimate human structure that exists within Judaism – that between husband and wife – there is no shortage of teachings of what is and what is not appropriate. One important takeaway from the value that our tradition puts on tzniut is that we must deeply value a person’s right to his or her privacy and that violating that space is to be viewed with the greatest of seriousness.

In this regard, we must relate directly to a very controversial and deeply offensive argument that is all too often made by some defenders of abusers: blaming the victim.

In this wholly misplaced argument, people are wont to say, “She had it coming to her” (in this case it is more often women who are the victims), because the girl or woman didn’t dress properly, or spoke in a way that gave the abuser an opening to progress with unwanted advances.

As critical as it is to stress that everyone must dress and behave in a way that promotes tzniut and morality, we must establish that in absence of their doing so, this does not serve to mitigate or explain the actions of an abuser. We must accept the responsibility to act in a respectful manner and we can never use the actions of another as a defense for a failure to do so.

All these understandings, which are based heavily on extensive Talmudic, rabbinic and contemporary teachings, must allow any reasoning person to appreciate that the Jewish outlook on sexual abuse, harassment and improper treatment of another should be perceived with the utmost seriousness – and demands a serious and unwavering response.

Despite that conclusion, as in all matters of legal and halachic decision-making, every case must be judged based on its individual merits, with a complex system of evidence and presumptions being taken into account.

But we feel confident that our conclusions should inspire a different perspective on how proponents of halachic Judaism relate to this movement.

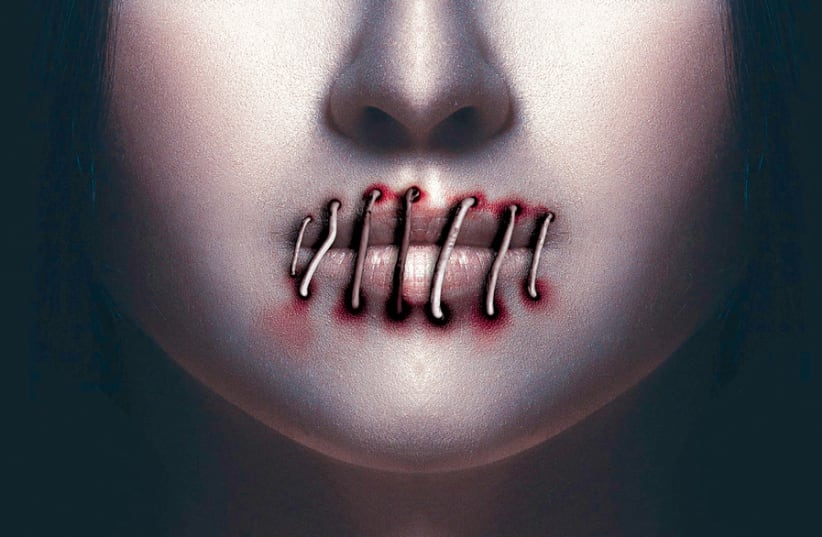

Specifically, if we are proud to champion our lives as built on justice, morality and dignity, then we must never look to silence the voices of victims of abuse.

Our role as rabbinic and community leaders must be to confront the realities of our society and be ready to respond to both the challenges and opportunities in an honest manner that protects our traditional values while firmly promoting human dignity in the modern world.

Rabbi David Stav is a founder and chair of the Tzohar Rabbinical Organization and chief rabbi of Shoham. Rabbi Avraham Stav is an educator and writer. This piece is adapted from an extensive halachic essay recently published in the Tzohar Journal (Hebrew).