A drop sheer as a crude gravestone.

I am afraid.

Today I am as old in years as all the Jewish people.

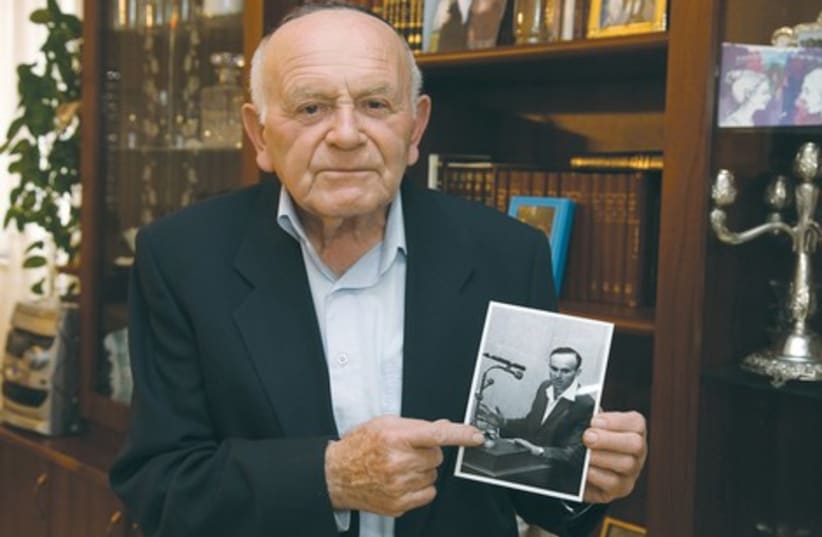

Now I seem to be a Jew.The public identification of Jews as the victims at Babi Yar and at Auschwitz was a bombshell for Soviet Jews.Despite the fact that the genocide of the Jews had been little reported in the Soviet Union since the war, consciousness of it had filtered through by word of mouth. Citing one survey conducted in the 1970s, Altshuler said he was as surprised as its authors to learn that the Holocaust (57 percent) contributed more to Jewish identity in the USSR in the previous decade than either the establishment of the State of Israel or the Six Day War, which has often been cited as the trigger ofthe refusenik movement. Instead, the Eichmann trial, which linked the Holocaust to Israel, was the key “component” of Jewish identification with Israel that burst into flame with the Six Day War.The Sabra ResponseIt has been said that by 1967 the Holocaust had become a key component of the collective Israeli mentality because of the Eichmann trial. How does one measure the extent of its influence? In 1947-48 Holocaust survivors were flooding into the country, there was tremendous sympathy for survivors in the US, president Harry Truman demanded that Britain permit the immediate admission of 100,000 displaced Jews. Yet Parchments of Fire, which documents soldiers’ feelings during the War of Independence, scarcely mentions the recent fate of Jews in Europe despite the fact that the odds against Israel’s survival were greater than they would ever be after that.Losses were expected to be great, but nobody thought to prepare mass graves in May 1948 as they did in May 1967. However, in The Seventh Day, a book of conversations with soldiers who participated in the Six Day War, allusions to the Holocaust are frequent.Some soldiers compare Arabs to Nazis, others reminisce about destroyed East European villages they never knew or worry that they might be brutalized by military success.“Our feelings are mixed. We carry in our hearts an oath which binds us never to return to the Europe of the Holocaust [a term that had only recently become the generic term for the destruction of the Jews]; but at the same time we do not wish to lose that Jewish sense of identity with the victims,” wrote kibbutz teacher and scholar Muki Tsur of the new consciousness.The new sensitive Israeli had arrived.The trial continued to affect Israeli society long after the Six Day War. Its impact was heightened by Arendt’s account, which often seemed to blame the victims for participating in their own destruction and thus undermining the whole educational purpose of the trial. “She was not right, but maybe precisely because of that her book touched off the entire field of Holocaust studies,” says Shalmi Bar-Mor, who between 1972 and 1995 was director of the department of education at Yad Vashem.The effects of the trial “unfolded slowly.” In 1963, before Arendt’s work was published, Abba Kovner, a leader of the Vilna Ghetto uprising and a selected witness at the trial, could still say, “We shall not bestow the title ‘hero’ on those who were exterminated in the slaughter pit. We, unlike others, shall not reserve a place for them in the Temple of Heroism. We dare not even say they died a martyr’s death.” During the 1966 economic recession suggestions were even made to close down Yad Vashem.Bar-Mor, whose parents left Warsaw before the war, believes one of the trial’s long-term effects was the 1979 introduction of compulsory Holocaust studies in high schools under education minister Zevulun Hammer of the National Religious Party, which led to organized school tours to sites of death camps in Poland.Following the 1977 mahapach, another “turning point,” which brought Menachem Begin’s Herut party to power, Holocaust consciousness rose to an entirely new level, culminating in talk of saving Lebanon’s Christians from a Palestinian-Syrian holocaust and besieging Yasser Arafat in Beirut as though he were Hitler in his Berlin bunker. The feeling of many writers on the subject is that the Holocaust has become too much a part of Israeli consciousness.IN CONTRAST to Arendt, whose attitude to the trial seemed to be well established before it began and did not change, Palestine-born Haim Guri, sabra, poet and Palmah fighter, emerged from it in a more sympathetic frame of mind. The Holocaust “had been a source of shame to us, some awful blemish,” he wrote in Facing the Glass Booth, but it was not, he adds, because Israelis were hostile. They just did not understand how it could have been. “A catastrophe this big takes time to digest and in 1948 there was no time to think about it.”As the testimony of witnesses unfolded, he too began “to understand from their detailed stories the utter paralysis in which the victims found themselves the whole time.” In that sense Hausner’s relentless questioning of witnesses, much derided by Arendt, was a success.Guri later made a documentary film called Maka Ha-81 (The 81st Blow) which accompanied film footage of Nazi persecution of Jews with a sound track of witnesses testifying at the trial. The title of the film referred to a dramatic episode during session 24 of the trial when Dr. Josef Buzminsky, who married the Polish woman who protected him, spoke of witnessing a beating administered to a teenager in the Przemysl ghetto in eastern Poland. He was astonished because “as a doctor I know that no child can survive more than 50 lashes like that.” He counted 80 and the boy survived. “And do you see him here? asked Hausner. “Yes, there,” he said pointing at the police interrogator seated next to Hausner.Though he had often mentioned the 80 lashes he received police officer Michael Goldman, specializing in Polish affairs, felt that no one believed him. “That was the 81st blow” said Guri. “It has entered Hebrew usage to mean a warning of peril which no one believes, as happened for example on the eve of the Yom Kippur War.” More broadly it means that after expecting to be consoled by friends, one finds oneself not only disbelieved but abandoned.Has this then become a national trait? Did the Eichmann trial have the effect that Ben-Gurion intended? According to Hanna Yablonka of Ben-Gurion University and author of The State of Israel versus Adolf Eichmann, “Two long-term effects of the Eichmann trial were felt by youngsters of both eastern and European origin. One was a new understanding of the importance of the existence of the State of Israel, and the other, perhaps even more significant, was the crystallization of a pessimistic outlook with regard to Israel’s place in the world.”