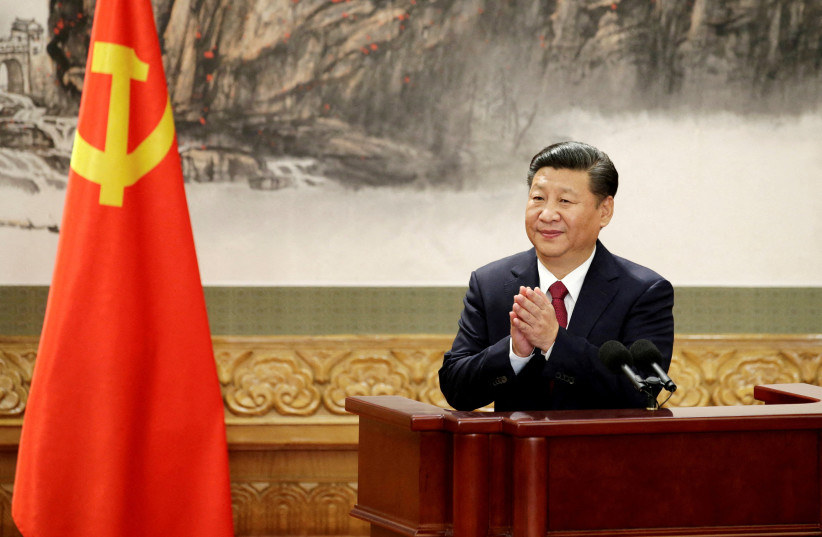

Saudi Arabia’s de facto ruler, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MbS), hosted Chinese President Xi Jinping at Yamamah Palace in Riyadh last week, flanked by high-ranking officials. President Xi said bilateral ties with Saudi Arabia had grown “by leaps and bounds” in recent years.

For more stories from The Media Line go to themedialine.org

This “has not only enriched both countries’ peoples but promoted regional peace, security, prosperity and development,” Xi said, according to China’s state-run CCTV. The two leaders oversaw the signing of a comprehensive strategic partnership agreement focusing mainly on energy, to “harmonize” Saudi Arabia’s ambitious economic reform agenda, Vision 2030, with China’s trillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative, the official Saudi Press Agency said.

China, the top consumer of Saudi oil, has been strengthening ties with a region that has long relied on the United States for military protection but has voiced concerns over American involvement and presence in the Middle East.

<br>Xi’s visit comes at a time when US-Saudi ties are at a low point

“It’s been conventional wisdom for at least the past decade, or even two, that the world – including the Middle East – has been undergoing a transition from an effectively mono-polar to a multipolar world, as US power is increasingly offset not just by Russia but China, India and possibly others like Brazil, South Africa or a more unified Europe,” Hussein Ibish, a senior resident scholar at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, told The Media Line.

The contrast between Saudi Arabia’s hospitality toward the Chinese president and the reception given to US President Joe Biden is clear, and what some sarcastically dubbed the US- Saudi “fist bump summit” had a completely different feel from the strong, intimate and warm handshake between MbS and Xi. This was Xi’s third journey overseas since the coronavirus pandemic began.

A top US official warned the Gulf countries about the risks of growing too close to China. “There are certain partnerships with China that would create a ceiling to what we can do,” Brett McGurk, the National Security Council’s Middle East coordinator, told a security conference in Bahrain in November.

Ibish says that Gulf states must look after their own interests first, and that’s why they are

diversifying their list of allies according to their needs.

“It’s possible that traditional US allies in the Middle East, particularly the three key security

allies – Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE – will continue to pursue strategic diversification,

reaching out to other global actors like Russia and China, and each other through agreements

like the Abraham Accords and other cooperation, but it’s also possible that there will be a

sustained demonstration of restored US will to act internationally.”

Despite all the assurances from President Biden that the United States will not leave the Middle

East and will always stand with its strategic allies in the region, there are still fears that

Washington’s actions say otherwise.

Eran Lerman, vice president of the Jerusalem Institute for Strategy and Security, told The Media

Line that the Biden Administration is really causing a serious disruption in the relationship with

Saudi Arabia, which has been central to the regional balance of power for the better part of 80

years.

“It reflects a sense of grievance on the part of the Saudis about American policy particularly vis-

à-vis Iran and the lack of support for the situation in Yemen.”

Riyadh and Abu Dhabi had asked Washington to redesignate the Yemeni Houthi rebel

movement as an international terrorist organization.

Lerman says from the point of view of the Gulf states, particularly MbS and Emirati President

Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, mistrust started with the “delisting of the Houthis, the

resumption of negotiations with Iran with various efforts to revive the JCPOA [Joint

Comprehensive Plan of Action, the Iran nuclear deal] and … the manner in which the US left

Afghanistan.”

Both Gulf states have complained about a lack of US support under President Biden in the

Yemen conflict.

In 2019, during a debate among Democratic Party presidential candidates, Biden didn’t mince words when he said he believed that journalist Jamal Khashoggi “was murdered and dismembered … on the order of the crown prince” and that as a result, he would treat the Saudis as “the pariah that they are,” a statement that, to say the least, didn’t sit well with MbS.

“His statement has not been forgotten. But to assume that the Saudis can reverse course in their total reliance on the US in terms of military hardware and air force support, that’s steep,” says Lerman.

Hasan Awwad, a US-based Middle East affairs expert, told The Media Line that the White House did not have the region atop its agenda.

“With having to deal with many crises, the Middle East ranks fourth on the list of US foreign

policy priorities after Asia, the Pacific, and Europe,” he said.

The White House said last week that China’s attempt to amass influence in the Middle East and

beyond was “not conducive” to international order.

Despite a denial from Gulf officials, the visit and meetings that took place in the desert kingdom

are viewed as further proof that Beijing’s influence in the region is rapidly growing, threatening

Washington’s longstanding status and interests.

In July, President Biden visited Jeddah, Saudi Arabia despite his 2019 campaign pledge to

ostracize the kingdom over its human rights abuses.

During his visit to Jeddah, the US president tried to assure the Saudis and their allies that the US

would remain fully engaged in the Middle East.

‘We will not walk away and leave a vacuum to be filled by China, Russia, or Iran,” the American

leader said.

But less than five months later, the Chinese president has made his own official visit to the

kingdom, where he inked mega-agreements between Riyadh and Beijing that worry

Washington.

“It is easier for authoritarian, dictatorial regimes to deal with similar-minded governments that

won’t question their record on human rights when they want to buy weapons,” explains

Awwad, adding that “it is easier for them to do so with Moscow and Beijing; as long as they

have their cash in hand, they have fewer restrictions on who to sell weapons to,” says Awwad.

The US lambasted OPEC+’s cuts in October, accusing Saudi Arabia of “aligning with Russia” and

coercing OPEC oil producers to cut production.

The question remains whether US strategic partners in the region can chart a new path for

themselves that doesn’t include Washington at the top.

“Not too much. They may be looking for strategic diversification, but they still ultimately need

US support to guarantee their core national security,” Lerman says.

He doesn’t believe the tension in relations is permanent. He says the constraining of ties is

meant to “rattle the United States so it does not abandon Saudi Arabia.”

“That’s not what we are talking about; we are talking about an expression of dismay that is

being manifested by shifting a little bit toward Russia and China. I don’t yet see a Chinese

equivalent to the US strategic pretense,” says Lerman.