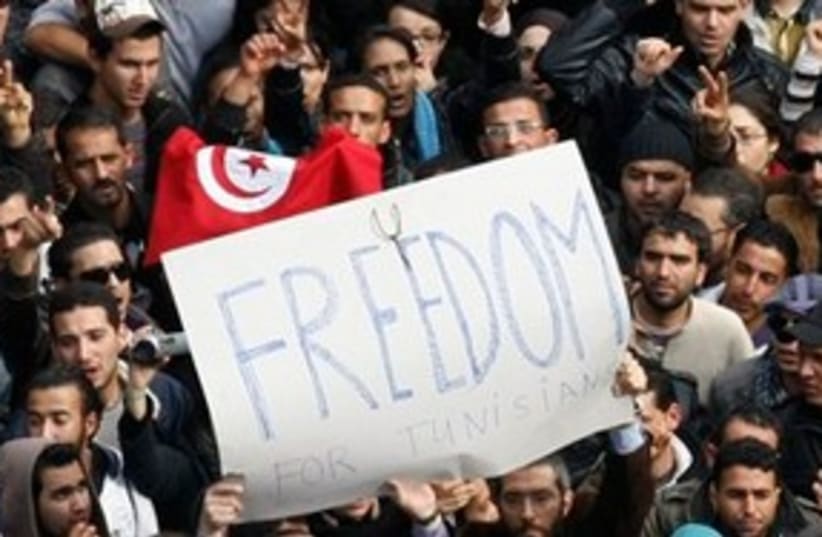

RELATED:As turmoil persists, Mideast leaders bow to pressureThe Region: Egypt gets its KhomeiniLibyan ambassador pleads to UN: Save our countryInspired by Tunisia’s example, other Arab states rose up against their own decades-long autocrats. Yemen, Bahrain, Algeria and Jordan have all seen unprecedented demonstrations, Hosni Mubarak was booted out of Egypt and Muammar Gaddafi in Libya may well be next.Distracted by uprisings elsewhere, the world has all but forgotten about Tunisia. Since Ben Ali’s ouster, the diminutive North African nation has been in a state of limbo, waiting to ride out a six-month transition period of military rule until presidential elections. The former prime minister has taken over as caretaker president, but last week saw the appointment of the third interim foreign minister in a month and the interior ministry filing for the complete dissolution of Ben Ali’s party.“The revolution in Tunisia has been very successful and it has become a model for the region,” said John McCain, the leading Republican on the powerful Senate Armed Services Committee, in Tunisia on Monday during a tour of the region with Senator Joe Lieberman (the two lawmakers stopped in Israel on Friday).McCain’s comments beg the question – could the country that gave birth to the so-called Arab spring serve as a model for a new kind of Arab state: secular, progressive and democratic?Bruce Maddy-Weitzman, a North Africa expert at Tel Aviv University’s Dayan Center, urged caution, noting that Tunisia is a small, homogeneous nation with a large middle class, and its model of government might be difficult to transfer to larger, more heterogeneous Arab countries.“It’s easier to create a popular uprising than to build viable civil institutions,” he told The Jerusalem Post on Thursday.Still, Tunisia represents what much of the West would like to see take root in the region.“Long dismissed in the Arab world as a neutered, pro-Western, Frenchified country, not to mention small, Tunisia now stands tall,” Katrin Bennhold wrote last week in The International Herald Tribune.The country has long been at the region’s vanguard on women’s rights: Tunisian women were the first in the Arab world to earn the right to vote, received abortion rights the same year as their US counterparts and have more seats in parliament than do women in the France. And women are well-educated – at 71 percent, they have the highest literacy rate of any Arab state and outnumber men among university graduates.“Polygamy is banned, marriage conditional on female consent and miniskirts as common a sight as the Muslim head scarf in Tunis’s cityscape,” Bennhold wrote.Images from Tunisia’s protests stood in stark contrast to those from rallies in other Arab states in that women in headscarves were distinctly in the minority.This apparent progressivism does, however, have a dark side, as it is the result of Ben Ali’s three-decade policy of promoting women’s rights as both a bulwark against Islamists at home, and as an alibi to Western governments inquiring about human rights abuses.The Nahda, or Renaissance, party is an Islamist group banned under Ben Ali that today retains a considerable support base. But unlike their Islamist counterparts in Egypt and elsewhere, Nahda leaders have issued clear, unambiguous signals that they do not seek a government based on Islamic law in the country.“We know we have an essentially fragile economy that is very open toward the outside world, to the point of being totally dependent on it,” said Hamadi Jebali, the party’s secretary- general, in an interview with the Tunisian magazine Réalités. “We have no interest whatsoever in throwing everything away today or tomorrow.”Nahda is allied with the Muslim Brotherhood, and its founding ideology was largely shaped by that of the Egyptian movement’s founder, Sayyid Qutb. But the Tunisian party has consistently compared itself with the Islamic party governing Turkey, which though religious in founding and nature, has stopped short of calling for the imposition of Sharia law.One thousand supporters welcomed back the movement’s long-exiled leader, Rached Ghannouchi, on his return to Tunis last month. He later gave an interview to Al- Jazeera television confirming that he supports democracy for Tunisia and is opposed to the reinstitution of the Islamic Caliphate.Still, Thomas Fuller of The New York Times reported a week ago that many Tunisians remain unconvinced.“Freedom is a great, great adventure, but it’s not without risks,” Fathi Ben Haj Yathia, an author and former political prisoner, told the Times. “There are many unknowns.”If Nahda is to gain any considerable support, it is likely to be in the more conservative inland than the freewheeling Mediterranean capital, where bikinis are a common sight, and wine is openly drunk in bars (as is many a local on a breezy February night).“It’s no coincidence that the revolution first started in Tunisia, where we have a high level of education, a sizable middle class and a greater degree of gender equality,” a Tunisian psychiatrist living in Paris told the IHT. “We had all the ingredients of democracy but not democracy itself. That just couldn’t last.”Tunisia is perhaps the Arab world’s best hope for secular, progressive democracy. If it succeeds, it may give Arabs around the region cause for celebration and a model for emulation. If Tunisia fails – turning instead to Islamism or dictatorship – it could be the first sign that the long-awaited Arab spring was merely a winter thaw.

Tunisia: Potential model of progressive Arab democracy

Analysis: N. African state set off a region-wide revolution, but can it also serve as an example of tolerant, forward-leaning governance?

RELATED:As turmoil persists, Mideast leaders bow to pressureThe Region: Egypt gets its KhomeiniLibyan ambassador pleads to UN: Save our countryInspired by Tunisia’s example, other Arab states rose up against their own decades-long autocrats. Yemen, Bahrain, Algeria and Jordan have all seen unprecedented demonstrations, Hosni Mubarak was booted out of Egypt and Muammar Gaddafi in Libya may well be next.Distracted by uprisings elsewhere, the world has all but forgotten about Tunisia. Since Ben Ali’s ouster, the diminutive North African nation has been in a state of limbo, waiting to ride out a six-month transition period of military rule until presidential elections. The former prime minister has taken over as caretaker president, but last week saw the appointment of the third interim foreign minister in a month and the interior ministry filing for the complete dissolution of Ben Ali’s party.“The revolution in Tunisia has been very successful and it has become a model for the region,” said John McCain, the leading Republican on the powerful Senate Armed Services Committee, in Tunisia on Monday during a tour of the region with Senator Joe Lieberman (the two lawmakers stopped in Israel on Friday).McCain’s comments beg the question – could the country that gave birth to the so-called Arab spring serve as a model for a new kind of Arab state: secular, progressive and democratic?Bruce Maddy-Weitzman, a North Africa expert at Tel Aviv University’s Dayan Center, urged caution, noting that Tunisia is a small, homogeneous nation with a large middle class, and its model of government might be difficult to transfer to larger, more heterogeneous Arab countries.“It’s easier to create a popular uprising than to build viable civil institutions,” he told The Jerusalem Post on Thursday.Still, Tunisia represents what much of the West would like to see take root in the region.“Long dismissed in the Arab world as a neutered, pro-Western, Frenchified country, not to mention small, Tunisia now stands tall,” Katrin Bennhold wrote last week in The International Herald Tribune.The country has long been at the region’s vanguard on women’s rights: Tunisian women were the first in the Arab world to earn the right to vote, received abortion rights the same year as their US counterparts and have more seats in parliament than do women in the France. And women are well-educated – at 71 percent, they have the highest literacy rate of any Arab state and outnumber men among university graduates.“Polygamy is banned, marriage conditional on female consent and miniskirts as common a sight as the Muslim head scarf in Tunis’s cityscape,” Bennhold wrote.Images from Tunisia’s protests stood in stark contrast to those from rallies in other Arab states in that women in headscarves were distinctly in the minority.This apparent progressivism does, however, have a dark side, as it is the result of Ben Ali’s three-decade policy of promoting women’s rights as both a bulwark against Islamists at home, and as an alibi to Western governments inquiring about human rights abuses.The Nahda, or Renaissance, party is an Islamist group banned under Ben Ali that today retains a considerable support base. But unlike their Islamist counterparts in Egypt and elsewhere, Nahda leaders have issued clear, unambiguous signals that they do not seek a government based on Islamic law in the country.“We know we have an essentially fragile economy that is very open toward the outside world, to the point of being totally dependent on it,” said Hamadi Jebali, the party’s secretary- general, in an interview with the Tunisian magazine Réalités. “We have no interest whatsoever in throwing everything away today or tomorrow.”Nahda is allied with the Muslim Brotherhood, and its founding ideology was largely shaped by that of the Egyptian movement’s founder, Sayyid Qutb. But the Tunisian party has consistently compared itself with the Islamic party governing Turkey, which though religious in founding and nature, has stopped short of calling for the imposition of Sharia law.One thousand supporters welcomed back the movement’s long-exiled leader, Rached Ghannouchi, on his return to Tunis last month. He later gave an interview to Al- Jazeera television confirming that he supports democracy for Tunisia and is opposed to the reinstitution of the Islamic Caliphate.Still, Thomas Fuller of The New York Times reported a week ago that many Tunisians remain unconvinced.“Freedom is a great, great adventure, but it’s not without risks,” Fathi Ben Haj Yathia, an author and former political prisoner, told the Times. “There are many unknowns.”If Nahda is to gain any considerable support, it is likely to be in the more conservative inland than the freewheeling Mediterranean capital, where bikinis are a common sight, and wine is openly drunk in bars (as is many a local on a breezy February night).“It’s no coincidence that the revolution first started in Tunisia, where we have a high level of education, a sizable middle class and a greater degree of gender equality,” a Tunisian psychiatrist living in Paris told the IHT. “We had all the ingredients of democracy but not democracy itself. That just couldn’t last.”Tunisia is perhaps the Arab world’s best hope for secular, progressive democracy. If it succeeds, it may give Arabs around the region cause for celebration and a model for emulation. If Tunisia fails – turning instead to Islamism or dictatorship – it could be the first sign that the long-awaited Arab spring was merely a winter thaw.