It is surely, by now, a poorly kept secret that Israel has produced its fair share of quality documentary footage over the past decade and a half or so. The locally made works and material from overseas featured in next week’s Docu.Text festival are undoubtedly of the highest caliber. And the variety spread isn’t bad either.

Over five days, from August 14-18, the National Library will host the 2022 edition of Docu.Text for the last time. The festival is, happily, not going out of business. It is simply due to relocate, with the library set to move from the Givat Ram campus of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, where it has operated for over 60 years, to state-of-the-art premises down the road, near the Knesset, before the 2023 installment comes around. “Hopefully, this will be the last time on the campus,” chuckles the artistic director. “Not that I have any problem with having the festival in the current building. We hold outdoor screenings with great sound and there’s nothing like the evening air in Jerusalem.” She’s right, there.

“Hopefully, this will be the last time on the campus.”

Ruty Rubinshtein

THIS YEAR’S lineup, which feeds off a collaboration with the 24-year-old Docaviv documentary film festival, is based on what artistic director Ruty Rubinshtein terms “the essence of the festival, which engages in the core areas of the routine operation of the library.” She breaks that down to “culture, creation, text in the widest sense of the word, memory and anything connected to documentation, personal and national.”

What's showing at Israel's Docu.Text festival?

That leaves ample room for subject matter maneuvering and it looks like Rubinshtein has taken full advantage of the generous thematic reach. The memory field of play is well catered for, with the likes of the 1341 Frames of Love and War profile of our undisputed king of war photography, now 91-year-old Micha Bar-Am. Like all the documentaries I managed to view in the run-up to the festival, this is a bare-knuckled and immersive portrayal of a man driven to get the shots he so desperately sought, come what may, and cast caution summarily to the wind.

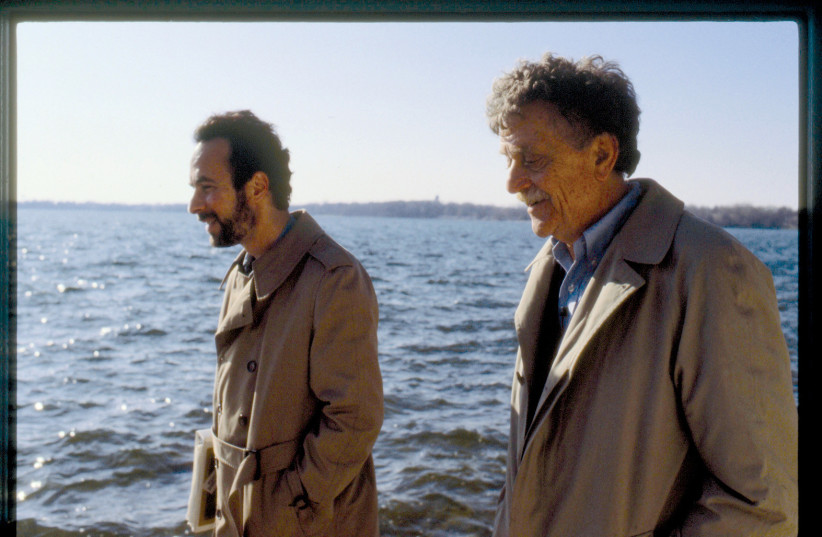

Then there’s Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time, by Robert Weide and Don Argott, which digs deep into the American psyche, and the celebrated writer’s singular tongue-in-cheek approach to life and his work. In fact, any which way you run your thumb across the 25-strong screening lineup you encounter top-notch compelling creations that make for riveting, enlightening and entertaining viewing.

Be My Voice, by Iranian Swedish-based filmmaker Nahid Persson, is a stirring affair as we follow exiled women’s rights activist Masih Alinejad careening along an emotional roller coaster. The Kaiser of Atlantis also tugs powerfully on the heartstrings, as it references the amazingly rich cultural goings-on at Theresienstadt concentration camp, focusing on the titular opera created in those immensely trying conditions by Czech-born composer Viktor Ullmann. The film seamlessly marries regular footage with deft animation as we learn about the opera that was never performed under Nazi rule but was miraculously discovered after the war.

Anyone with Anglo connections and who has been living in Israel for, say, over 40 years, or may just be interested in the lay of the land here back in the day, should get a kick out of watching The Camera of Doctor Morris. What might have been a run-of-the-mill account of Eilat when it was a remote outpost, and how a British couple and their children got on, as the still young state and even more rudimentary developing Red Sea shore town began to find their feet, turned out as a fascinating chronicle of the Morrises, and physical and emotional continuum of Eilat.

BUT WHEN it comes to raw emotional stuff, Back in Berlin has got most of them beat. The film, which was completed last year just in time to participate in the Haifa Film Festival where it won a Special Jury Mention, documents British-born Israeli director Bobby Lax’s moving trip to Berlin, where his father was born and from which he fled to the UK at the age of 15 on a Kindertransport.

There are numerous layers to the film all naturally connected to the Holocaust, although some more indirectly than others. There is the relationship between Lax and his oldest childhood friend, British-bred Manuel who, notwithstanding his Spanish given name, has German parents. The friendship between the two is a major component of Back in Berlin, and we go through the mill with that too. Manuel also has a dark family connection, which also serves to stir the emotional brew.

LAX, A seasoned filmmaker and actor who made aliyah 30 years ago, says he did not approach Back in Berlin lightly but still got a lot more than he’d bargained for. “It was a very cathartic experience for me in many respects, both on a personal level in which, via the film, I resolved a lot of issues that I had with my dad. I came to a much deeper understanding of who he was as a father and as a person. It was also very cathartic for my relationship, in the broader sense, with Germany today.”

I was glad to hear that. There is a scene when Lax arrives in Berlin, for the first time, and he is clearly disturbed by being there. It would not be putting too fine a point on it to say he looked terrified. “Every time I watch that scene, I wonder if it succeeds in putting over the depth of my emotional turmoil then. I felt so completely disorientated and full of fear.”

It was a release. It opened up the release valve on a pressure cooker that had been on a high flame for a long time. “It’s a lifetime, not just as a Jew but also as an Israeli, of regarding Germany in a certain way. That was almost insurmountable. So, it was certainly cathartic, and very much therapeutic. It resolved a lot of issues for me.”

It may have been a rush to get the documentary done and dusted in time for last year’s Haifa showing but Back in Berlin was not a whistle-stop job. “It was five and a half years in the making, from end to end,” notes Lax. “It was a process.” A process that gradually bifurcated and led off along previously unexpected trails.

The Manuel sidebar which became a central theme is just one example, as we learn of his sinister familial backdrop. We also meet his aunt, the German-born widow of famed American film director Stanley Kubrick, Christiane née Harlan. Manuel and his aunt have differing stances on their German roots, which also serves to challenge Lax’s own view on his father’s country of birth.

A LOT can happen while you’re getting on with making a movie. And it did. As Lax made his way through the emotive material he accessed when putting the documentary together, all sorts of things came to light that set him considering new angles and lines of thought. “It was five years in the making. What was a side story that turned into the main story was what Manuel and I went through, together, in the course of those five years.” It wasn’t just about their friendship. The epiphanous offshoots also impacted how Lax felt about a nation he’d more or less consigned, en masse, to the nether regions of the morality stakes. “For me, it was an eye opener. I’d never thought about what it’s like to be German. I’d only ever seen it from our [Jewish] perspective and I think if anyone attempted to give me a German perspective, I would have been absolutely abhorred by the idea of having to contemplate that.”

I get that entirely. On a recent trip to Germany, I met a young Austrian, who now lives in Germany, who told me about his parents, who had grown up with the guilt of being German despite the fact that they were communists and had only just about escaped being persecuted and, possibly, killed for their political beliefs. “Speaking to Christiane Kubrick it was a revelation to hear a German wanting to absolutely deny any connection to the German language, German identity and German culture. As she says in the film, she was just glad to change her name [after she married] and change her identity. She says, when people say to her she doesn’t look very German or sound very German, she says ‘Oh good!’” Lax laughs.

Working on the film, Lax says, also enlightened him about the broad spectrum of mindsets in Germany, regarding their national identity. “Even in Christiane’s family, some more embrace their Germanity, particularly the new Germany, in a very positive way. For Christiane, it was something she wanted to completely disconnect from.”

Lax says he is looking forward to the Docu.Text screening. In fact, the film has already been shown around the world, including in the US, his father’s city of birth and South Korea, with more lined up for the Netherlands, the UK Jewish Film Festival in London, and at additional places around the US. “I’m pleased to say, I’ve had a fantastic response to the film. If it’s thought-provoking and it’s got other people thinking about these things, as well, then I think we have achieved something.”

He certainly has. There are so many twists and turns to the storyline, and emotional powder kegs blowing up along the way, ultimately in a positive and rewarding manner. As the son of a Kindertransport Holocaust survivor myself, the documentary certainly resonates powerfully with me and arouses strong emotions. But, to paraphrase an old Yiddish joke, you don’t have to have familial Holocaust connections, or even be Jewish, to get the stratified moving message in Back in Berlin. ❖

For tickets and more information, visit: docutext.nli.org.il.