Brett Morgen puts in a shift, or two. When I caught up with the film director, in a phone call to his LA home, it was 11 p.m. on his end. “I apologize for my tired voice, I’ve been up since 5 o’clock in the morning,” came the somewhat weary opening greeting. Part of that was down to being shortlisted for an Oscar in the Best Documentary category for his work on late rock icon David Bowie, Moonage Daydream, and waiting to see if it made the final cut.

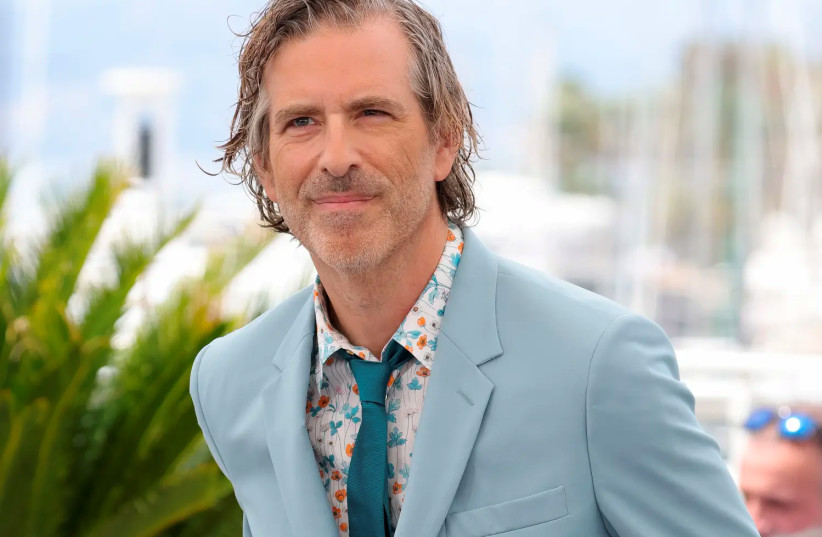

Unfortunately, the film didn’t make it to the final five nominee group but it has been shown around the world since its release in September to wildly enthusiastic responses. When the rockumentary was unveiled at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, Morgen received a long standing ovation from the audience in the cinema.

Now he is coming here to attend a doubleheader at the Tel Aviv Cinematheque, on January 29-30, with the screening of the Bowie work on the second day preceded by Morgen’s acclaimed 2015 profile of late Nirvana rock group frontman Kurt Cobain Montage of Heck. Morgen will also take part in a discussion about the movies at the Cinematheque.

A program with a packed punch in Tel Aviv

That’s a program with a packed punch, which takes place under the auspices of Tel Aviv University’s Steve Tisch School of Film and Television. It also provides Morgen with an opportunity to come back here, following his 2016 Montage of Heck berth in that year’s Docaviv documentary film festival, in Tel Aviv. Morgen will also be conducting master classes for a week with students in the school's international documentaries program.

Having caught Moonage Daydream when it made its way over here a couple of months ago, I can attest to the potency of the movie and the almost feral impression it left on me. It didn’t really send me back to “Space Oddity,” which came out in 1969 and knocked me for six, or his 1972 incarnation as Ziggy Stardust as glam rock took hold. But it did provide me with an enlightening and immersive look at the man and the artist.

“To me, the opposite of experience is information,” says the 54-year-old director. “In the biographical route, I think that information is often best conveyed through the written word. If someone wants to know about the life of Jane Goodall, or the life of David Bowie, they are going to be better served reading a 1,200-page book than watching a two-hour movie.”

Clearly, Morgen has wider interests than just the rock world, and deeper intent than informing us about what the subject has done and when. Goodall is an 88-year-old British anthropologist and primatologist who gained worldwide renown for her pioneering work with chimpanzees in Africa, which began in the late 1950s.

Morgen’s 2017 moving portrait of her, simply titled “Jane,” managed to impart Goodall’s sense of unrestrained wonder and joy with wildlife and nature. You get a similarly undistilled open-eyed and open-hearted account of the British rocker in Moonage Daydream.

He makes no apologies for his bare-knuckled take on Bowie. “What we achieved with our movie is something that cannot be attained from a book. Moonage Daydream is sort of injecting Bowie’s resume into the viewer’s veins.” If one buys into the “sex, drugs and rock and roll” epithet attached to the musical side of 1960s counterculture, the intravenous analogy looks to be spot on.

MORGEN WAS too young, at the time, to be conscious of Bowie’s impact on the global rock community and, one might venture, on the performance art genre as a whole in its initial stages in the late 1960s and early 1970s. However, he says the music of the artist who went through numerous metamorphoses, some fundamentally bizarre that caught unsuspecting pop and rock followers completely unawares, changed his life forever when he was 13 years old.

It was that jolt of consciousness that he was keenest to get across, along with some of what the preeminent creative groundbreaker got up to on stage, and in the recording studio.

“My goal was not to follow the traditional approach in documentaries, in pursuit of truth. For me, I don’t feel that understanding the highlights of David Bowie’s life and career leads to a deeper understanding of Bowie. To me, the best way to get close to Bowie is to allow him to articulate his experience predominantly through the source, and allow the art to tell the story.” Naturally, it helps if you have free rein to troll the rocker’s enormous archives of visual, audio and written work. Morgen had that.

In fact, the idea for a biographical work came up back in 2007, when Mogen initiated a meeting with Bowie in New York to discuss the possibility of making a non-fiction film. Bowie was taking something of a furlough from the business at the time, and nothing tangible came out of that session. The project sprang back into zestful life nine years later when Bowie’s ended, at the age of 69. Morgen contacted the Bowie estate and proffered his idea for what eventually became Moonage Daydream.

Morgen not only allows the art to tell the British legend’s story, he allows Bowie to spell it all out in his own words, as we hear recordings of him talking about the way he saw things. There is footage of gigs, as well as the odd interview sliver, from across the half-century of Bowie’s career, as the film provides us with a kaleidoscope montage of contextual slots.

The director also enjoyed unlimited access to the Cobain family’s documents for the making of Montage of Heck. He sees common denominators between both men and their art, and says it wasn’t a matter of trying to set the record straight for two tragic and misunderstood characters.

“I don’t think they were misunderstood at all,” he declares. “I think they were brilliant communicators. That was their gift, that they were able to connect with audiences in very different ways.” Then again, at least in the Nirvana leader’s case, Morgan feels the public did not get the whole story.

“When Kurt Cobain expressed himself in his lyrics, oftentimes it was sung with such incredible melody that people would miss the real meaning and the pain that was there.”

“When Kurt Cobain expressed himself in his lyrics, oftentimes it was sung with such incredible melody that people would miss the real meaning and the pain that was there.”

Brett Morgen

One would be forgiven for thinking that Cobain, who committed suicide at the age of 27, and Bowie had little in common. They were the product of different sociocultural backgrounds and came from different generations. They also had their own individual style of expression, visually and sonically.

Even so, Morgen believes there is a yin-yang connection between the pair. “I think that David and Kurt, in the two films, are like two sides of the same coin. One is about light, one is dark. For one, almost every moment of their life was hurtful and painful, and for the other one, every moment was an opportunity for growth. One film is a celebration of life, about someone who would have loved to do it all again, and the other one is about Kurt who took his own life.”

Morgen seems to embrace that flipside take in the oxymoronic nature of the comparison. Diverging lifestyles and performance philosophies apart, the director places them in the same left-field artistic bracket.

“They were similar in their ability to communicate feelings that were not being expressed in mainstream culture at the time when they were most relevant and active. They are both incredibly inspiring.”

The same could be said for Montage of Heck and Moonage Daydreams. Why the Bowie bio did not make the Oscar nominee stage is anyone’s guess.

For tickets and more information: www.cinema.co.il