It is not very often that we get a chance to see a manuscript that was created over a millennium ago. Should you make your way over to ANU – Museum of the Jewish People in Ramat Aviv sometime over the next week, you will be able to get up pretty close to the Codex Sassoon. The ancient tome will be on display there March 23 through to March 29.

The codex gets its name from a previous owner, David Solomon Sassoon, who purchased it in 1929 for a princely £350. That was the first the world had heard of the volume for around 600 years, after it disappeared from view following the destruction of the Syrian synagogue where it had been housed.

It is now enjoying a furlough in Tel Aviv – after a showing in London – before it goes stateside to Dallas and Los Angeles, whereafter it will be put up for sale at Sotheby’s in New York. The auction house places the manuscript’s origin, based on scientific and paleographic testing, in the late ninth or early 10th century and believes the hefty volume will go for somewhere between $30 million and $50m. If the bidding scales the upper end of that price bracket, it will make the Codex Sassoon the most expensive manuscript ever sold by auction.

What makes the Codex Sassoon so special?

CODEX SASSOON – aka S1 – is not the only ancient copy of the Bible around. The Aleppo Codex is a well-known artifact in the biblical field. Written in Tiberias in the 10th century, it was authenticated by none other than the venerated 12th-century philosopher and Torah scholar Maimonides.

Its moniker references the fact that it was kept at the Central Synagogue of Aleppo for five centuries. The world lost sight of it in 1947 after the synagogue was burned down in anti-Jewish riots, and it resurfaced in Israel 11 years later. However, excitement at the discovery was tempered by the fact that it was found to be far less complete than had been hoped, with around 40% missing, including a large part of the Torah section.

The other major A-lister in the biblical manuscript category is the Leningrad Codex, which is thought to have been written in Cairo in 1008. The codex has resided in Saint Petersburg (formerly Leningrad) at the National Library of Russia since the mid-19th century.

Prof. Yosef Ofer, who lectures in biblical studies at Bar-Ilan University, is looking forward to a rendezvous in Ramat Aviv with the Sotheby’s auction item.

“I saw it in Geneva a few years back,” he says. He was allowed more privileged access than most at the time.

“I spent four days examining it. I took a series of photographs. I had direct contact with it. I am delighted that it is coming to Israel and that people here will be able to take a look at it, too.”

Naturally, we ordinary mortals will not be able to merrily leaf our way through the timeworn parchment pages of the valuable manuscript.

“The public will only be able to see two pages that will be displayed. There are 800 pages in the manuscript. They can’t disassemble it to show it all to the public.”

Yosef Ofer

“The public will only be able to see two pages that will be displayed. There are 800 pages in the manuscript. They can’t disassemble it to show it all to the public,” Ofer notes somewhat superfluously. “Perhaps there will be pictures of more pages in the display.”

In fact, the double spread in the showcase cabinet will be complemented by a video showing other sections of the codex.

This week’s exhibit is a momentous occasion on various counts.

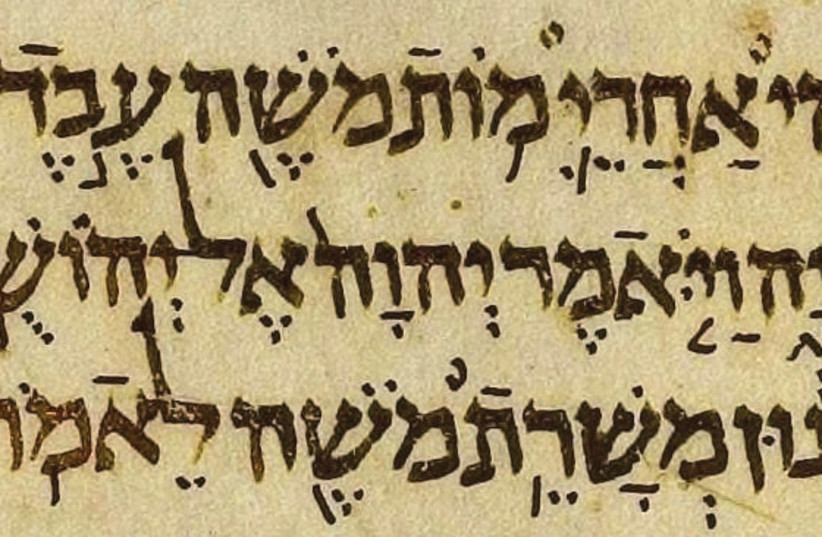

“The Codex Sassoon belongs in the same league as the Aleppo and Leningrad,” Ofer observes. “These are three special manuscripts of the whole Bible, very old and with Masora notations that represent the approach of the ba’alei masora.”

The addenda in question refer to a system of rules and instructions designed to keep scholars and readers on the reading straight and narrow by maintaining the accuracy of the Scriptures. The biblical text is considered sacrosanct, and every word and letter of the text must be read and conveyed in a precise manner. Hence the Masora, which is believed to have been developed in the ninth or 10th century by the Masoretes, families of scribes – or sofrim.

All three codices are, of course, highly prized Judaic works that help us follow the guidance of our learned predecessors and preserve generations-old traditions. Ofer says the Sassoon tome is the least familiar of the triad, and brings some added value to the field. “The Leningrad Codex came out later, and the Aleppo is very incomplete.”

Still, it is very much a matter of pooling the available resources in order to get as near as possible to the source.

“The other two served as the basis for various editions of the Bible over the last decades,” Ofer continues. “The Leningrad Codex is really complete. You can follow it almost exclusively.” That is not the case with the Aleppo version, which is also known as Keter Aram Tzova or Crown of Aleppo. “There are too many parts missing from that,” Ofer notes.

At the end of the day, the most definitive version of the Bible is an amalgam of the various codices and their Masora additions. “We need to combine them so that we understand the rulings of the ba’alei masora.”

Studying the Mesora

THERE IS an old saying that goes, “Ask two Jews about anything, and you’ll get three opinions.” We certainly have a tendency toward the contentious and expressing our views as clearly and, generally, as vociferously as possible. That is not necessarily a bad thing. Discourse, as long as it is respectful, can lead to the mutually beneficial exchange of ideas and, hopefully, generate new ways forward and innovative solutions.

However, when it comes to Masora, surely the idea is to arrive at a single defining narrative rather than leaving matters open to even more interpretation.

“There was a Masora center in Babylon and a center in the Land of Israel. There were quite a few differences between them,” Ofer explains.

That doesn’t sound too promising for anyone looking for a bedrock version. Ofer points out that the Codex Sassoon adopted an accommodating line.

“One of the interesting elements of this manuscript is that it says, for example, that with regard to a particular word, there is a debate between the Babylonian and Land of Israel versions, and it explains what the difference of opinion is. It will say, for example, that according to the scholars of Tiberias there are four instances of a particular phenomenon, and the Land of Israel edition adds two more.”

The Aleppo Codex took a more single-minded approach. “Keter Aram Tzova didn’t follow that line. It adhered to one system and ignored all the others. It didn’t document them,” says Ofer. “There were differences between the masranim (ba’alei masora). With the Codex Sassoon, the masran often talked about the Masora of Tiberias and the Masora of Babylon.”

While Ofer notes the lengthier time line of the Sassoon manuscript, apparently longevity is not always the be-all and end-all. “When it comes, for instance, to the Oral Torah, the Halacha, we don’t rule on halachic matters according to the Mishna [from around 200 CE] but based on the Shulhan Aruch [written in the 16th century].”

Still, this is the Bible we are talking about, and it would be nice to have something clear cut to lean on, if at all possible.

“The question is what did the ba’alei masora really decide?” Ofer continues. “In order to get to that, we need to look at manuscripts of this kind, these codices, which were written by ba’alei masora based in Tiberias. There are differences between them, too – not major ones; things like where words are written in full and where they use the shorter version.” That can refer to, for example, the use of a holam punctuation mark or the sound “o,” or writing the letter “vav” followed by a holam to produce the same sound. The word is read the same, but considering the sanctity of every single letter in the Torah, that would appear to be of great importance. That is where the notes in the margins come into play. “To decide on things like that, we look at the Masora notation in order to get to the accurate version,” Ofer says.

If anyone can guide us toward the right Masora, it is Ofer, who has spent much of the last five years researching the Codex Sassoon and decades delving into the Bible and the way the text should be recited today. Then again, that is far easier said than done. While Ofer points to the accuracy of the Aleppo Codex, there is the great disadvantage of the expansive missing sections. “That is why we need other ancient references. Here we have a very ancient manuscript [the Codex Sassoon] which also cites Masora notation from [Keter] Aram Tzova.”

This is clearly a complex business. On the one hand, we have a fervent need to follow the word of the Lord as passed down through the Torah. But there is also an inherent capacity for arriving at a broad range of interpretative understandings of the written letter. After all, according to medieval wisdom, which feeds off much earlier observations of the Sages, there are “70 faces to the Torah.” In other words, the ability to read the Scriptures in different ways is intrinsic to the source.

However, Ofer stresses that this does not relate to fundamental contrasts that may cause chasms between warring camps of Jewish thinking and practice.

“The differences are in the minutiae. They don’t mean that there may be another word here or there. That primarily relates to plene spelling or deficient spelling,” he says, referencing the aforementioned syllabic presentation, using a letter and a punctuation mark or making do with just a dot, such as a holam.

“You could have, for example, the word ‘kolot’ (sounds or voices), which could be written with two vavs or without either of them.” That would mean that the full spelling has five letters, while the shorter version has only three. Surely, that is a significant discrepancy. But there don’t appear to be any hard and fast rules. “In the same pasuk [verse], you can have the same word twice – once spelled fully and once deficiently,” Ofer adds.

OFER HAD his work cut out for him when he got into the nitty-gritty of the manuscript he scrutinized from such close quarters in Geneva, and which we will finally – albeit briefly – get to see with our own eyes in the coming week. As a researcher, by definition you have to be willing to put in several shifts to gradually find your way through the strata and offshoots in order to gain and convey a better understanding of the raw material. When it comes to Jewish Scripture, with its threescore and ten facets, that is a given.

“I focused on this [Sassoon] manuscript, and I examined every Masora note, one by one. There are 4,000 Masora notes, and I drafted an edition based on that. I needed to do that. I needed to understand what happened with this.” The said footnotes also engage in the ta’amei hamikra, the cantillation marks that guide those who read the weekly portion to the congregation in Monday and Thursday morning services, on Shabbat and on other holy days.

The codex was a work in progress. “There were different phases of work with this manuscript, and different masranim who added notes,” Ofer explains. Hopefully, before too long we will be the beneficiaries of the researcher’s painstaking work. “I have prepared a book on that. It hasn’t been published yet, but I hope that will happen soon.”

THAT SHOULD shed some incisive light on the nuances of the venerable text and the annotation, some of which we can now see for ourselves. Sharon Mintz, senior specialist, Judaica, Books and Manuscripts Department at Sotheby’s in New York, who landed here on Monday afternoon together with the precious tome, was clearly delighted to bring the codex “back home.”

“This has to be my most exciting journey to Israel. And I have made many in my years,” she says. “Bringing the earliest, most complete copy of the Hebrew Bible, with all 24 of the books, to the land of the People of the Book is fantastic.” Succinctly and emotively put.

The Codex Sassoon really is a star of the ancient biblical field with, as Mintz points out, only 15 of the 929 chapters missing. Like Ofer, Mintz is among the privileged few who have been allowed to get to grips, literally, with the manuscript. She says she feels blessed to have had that opportunity. “You open up it up and you feel the millennium, actually more than a millennium, of history sitting in front of you.”

It is not just a personal experience. “It also tells the story of the Jewish people because it was written in Israel or Syria, and we see it is dedicated to a synagogue in Syria. Then it went to private hands, and then we lost track of it. Then it reemerges over five centuries later not much worse for the wear. People are pulled to it magnetically. It is not just a physical object. It is monumental.”

Mintz says she is looking forward to observing how the Israeli public reacts to the codex in Tel Aviv. She witnessed similar dynamics in a gallery in London, where the manuscript was put on display for a few days. It also reflected the importance the work has for other religions.

“I got a little taste of that in London. We didn’t do a lot of advertising, but the word got around. There were yeshiva boys, Jehovah’s Witnesses, rank and file, and we had a little group davening Mincha in the corner,” she laughs.

“People in all walks of life, for whom the Bible is a very powerful document, the word of God, are drawn to it. It is not just for the Jewish people. It is also important for Christianity and Islam.”

This is probably a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for Israelis to see the actual Codex Sassoon, in actual corporeal form. It should be interesting to see who turns up at ANU next week.

Entry to the codex display area is free with prior registration at: tickets.anumuseum.org.il/show/542