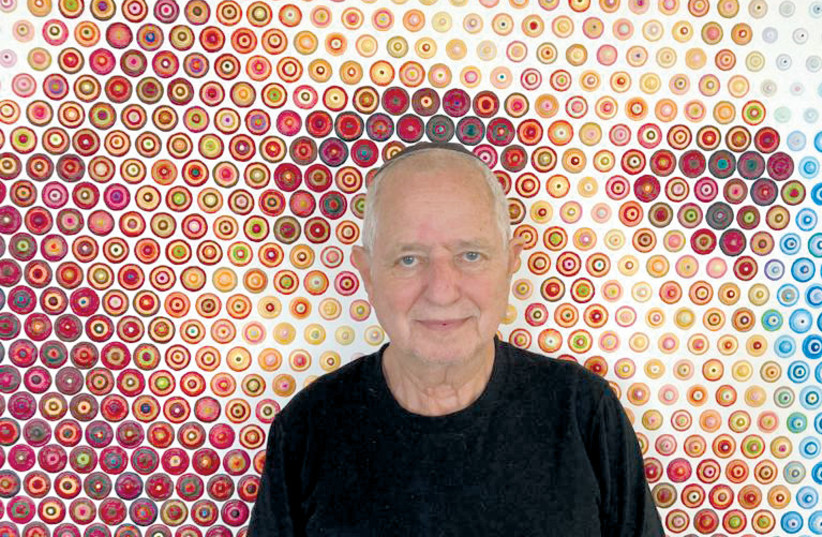

Gavin Rain is something of a blast from the past.

The 52-year-old South African painter has built up an impressive portfolio and gained an international name for himself, largely as a result of the neo-Pointillist portraits he creates of well-known figures. The likes of Marilyn Monroe and Audrey Hepburn have become preferred subjects, but a while ago he turned his practiced hands and imagination to something far more pertinent, and recognizable, for this part of the world.

On April 24, the Jerusalem Biennale Gallery in the old Shaare Zedek Hospital building on Jaffa Road will host Rain’s Prime Ministers in Perspective exhibition as part of the current Jerusalem Biennale, founded and stewarded by Rami Ozeri. The show, which was conceived by Johannesburg-born and bred, now Netanya resident, Myron Zaidel, features a dozen of Israel’s past leaders, beginning with the state’s first prime minister David Ben-Gurion, through to the current national honcho Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. The event also neatly straddles the country’s 75th anniversary.

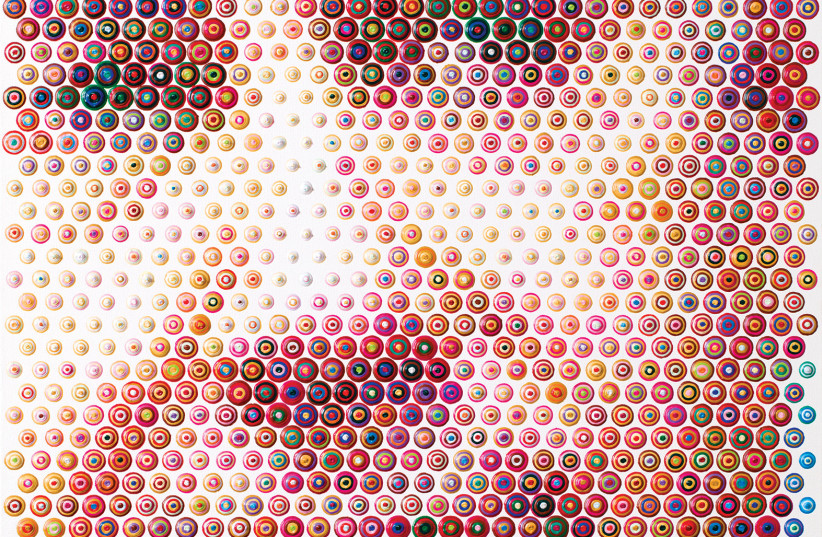

But these are not just any old portraits. The mostly one-meter square depictions comprise hundreds of concentric quintuple circles of paint arranged to produce the desired documentary effect when viewed from a suitable distance.

Rain is clearly willing and able to put in a shift or two. Not for him the latest technological gizmos which might have cut down on the creative process but which, he says, would have produced a below-par end result. “I don’t get a lot of time off [between painting sessions]. It takes a lot of time to do this,” he laughs. “The painting itself is very labor-intensive.”

“I don’t get a lot of time off [between painting sessions]. It takes a lot of time to do this. The painting itself is very labor-intensive.”

Gavin Rain

A predilection for the old-school approach

YOU COULD say Rain’s predilection for the old-school approach is built into his genetic backdrop and partly stems from his early exposure to a different artistic discipline.

“My grandfather was quite a famous landscape photographer in Cape Town, back in the day,” he explains. “I kind of grew up in his darkroom.” There, as a youngster, Rain witnessed the magic of an image gradually taking visual form as it insinuates itself on a previously blank sheet of paper.

Years later, he was drawn into the art form and earned a crust by teaching photography at the Cape Town School of Photography. He was initially happy to go with the contemporary technological flow which, he surmises, his antecedent mentor would have dug, at least to start with. “I taught on the digital side, which had just become a new thing. I always wonder what my grandfather would have thought of digital. I think he probably would have loved it. He loved technology and the new things it could do.”

However, Rain believes, the love affair would probably have fizzled out before long. “I think he would have loved it initially, and then he would have seen that, at that time certainly, it was vastly inferior to film. Film captures such a beautiful subtle range of tones which digital, of course, is incapable of. I mean, digital literally stands for distinct interval.” He has a point, at the very least, in pure technical terms.

FOR THOSE of us enamored of the benefits of contemporary technological conveniences, it is probably puzzling, if not downright mind-blowing, that anyone should choose to put so much time and physical effort into producing a work of art which, after all, is really a cover version of an extant image. Rain steps back through the corridors of time to feed off seminal influences such as late-19th-century French pointillist pioneer Georges Seurat and, a more recent proponent of the fragmented compositional approach, American painter Chuck Close, who produced large-scale photorealist portraits.

All that stood Rain in good stead when he took on a commission from one of the leaders of his local Jewish community, which eventually led to the prime ministerial venture. “I got a call from Rabbi David Masinter in Cape Town. You’ve got to watch rabbis. They are brilliant,” he chuckles. Masinter serves as director of Chabad House in Johannesburg and was looking to recruit Rain to help him generate some much-needed revenue. “He was raising money, and I said of course I would help him,” the artist recalls. “I said I would do a portrait of the [Lubavitcher] Rebbe.”

The spirit may have been willing, but there was a challenging technical minefield to be negotiated if Rain was going to do the late spiritual leader justice and enable Masinter to achieve the requisite sale price for the work. “I thought, ‘How in the world am I going to pull this off? This is going to be impossible in my style. There is all that beard!’”

Trademark hirsute feature notwithstanding, experience told Rain to look for a visual hook to point the way forward. “Then I realized that, actually, the thing about the Rebbe that is scintillating are his eyes. You can tell his entire personality from those flashing eyes. I thought that if I can just get the eyes right, then everything else is irrelevant.”

Rain didn’t know it at the time, but that inaugural foray into Jewish portraiture also helped to lay the groundwork for the current show. “That was sort of a primer for me,” he says. “When Myron [Zaidel] approached me and said ‘I want to do this project,’ I thought, ‘This isn’t impossible.’”

There was, however, a gender-related sticking point. “I never paint men,” says Rain. “It is exceptionally rare. I have, maybe, painted five or six.” This isn’t a matter of gender bias; rather, it is down to simple physiological elements that test Rain’s ability to convert into artwork form. “A woman’s face is far less complicated. That just has to do with shapes of faces. Women’s faces are far less angular, there is far less that you need to express.” Then again, that is not a blanket fact on the ground. One slot in the prime ministerial series proved to be a rule-bending dome scratcher. “That is not true for all women’s faces. Golda Meir, for example, has a very strong face, so there is a lot of characteristic wrinkle and stuff like that. She was really a character.” Indeed. The non-PC quip back in the day – diplomatically put – was that Meir was “the only man in Ben-Gurion’s cabinet.”

There are, apparently, all sorts of forces that come into play in producing the aesthetic bottom line. In the past, Rain has talked about how the artist is just one of the components in the creative continuum. He includes the client in the time line. “You are also thinking in terms of your patron,” Rain observes. “If you have a painting commission, you are also thinking in terms of what their needs are. Myron obviously wants this body of work to be something that is viable. It is a visual expression of his reality, of his interests and desires.”

If Zaidel had any agenda behind the decision to turn to Rain, it was purely historical. He says he never intended the paintings to convey any political subtexts. “This is not a political statement by any means,” he points out. “It is not a belief in this one [leader] more than that one. It is simply a historical rendition of the prime ministers of Israel – good or bad, it doesn’t matter.” In these tempestuous times, anything inclusive and non-divisive offers some welcome respite.

THE SEED for the whole venture began germinating after Zaidel came across Rain’s portrayal of the Lubavitcher Rebbe.

“I thought the art form is wonderful, the outcome and all the [visual] discussion points are excellent. You can view it from different angles and see many different images,” he explains. “That piqued my interest.”

That may have pushed Zaidel in Rain’s direction, but did the former consider that the artist, as a non-Jew who has never been to Israel, might not quite capture the spirit of his subjects? As technically adept as artists may be, surely, they still have to achieve a good grasp of the person behind the facial veneer in order to come up with the goods and convey some of the uniquely personal subtexts. Zaidel says he had no qualms at all.

“I met Gavin and spoke with him. I told him I’d seen his images of the Rebbe and that my [art collector] niece had some of his works, and I asked him if he would possibly be interested in doing a project for me.” Rain responded in the affirmative, and eventually the raw material for Prime Ministers in Perspective came to be. That was in 2020, and a dozen paintings were completed that year.

ALL SYSTEMS, it seemed, were go. Rain conducted the requisite research and studied numerous images of this country’s leaders since the state’s dawn in 1948. Presumably, I suggested, he now knows a lot more about our history than he did before he got down and dirty with the statespeople portraits. “Yes and no,” he responds somewhat edgily. “Israel has a vastly complex political history,” he notes.

“It’s also a very subtle political history, more than almost any other country in the world because Israel’s had to navigate some unbelievably difficult things and in a very short period of time.” Clearly, the South African has managed to get at least part of the delicate balancing act picture in this fragile part of the world. “It is fair to say that these leaders also had to walk some difficult political tightropes.”

Even with that understanding safely taken on, Rain was not exactly ready to write a book on the subject. “So for for me to understand the complexities and subtleties of that – absolutely not,” he states. “I would be lying if I said I had even the remotest understanding of that. It is a vastly complex thing, and I would have to spend many years studying it – as Myron has done –to understand.” Still, judging by the concentric circle-based depictions he came up, he got a decent slice of the characters behind the well-known faces.

But even with that in place and the wealth of professional experience Rain has accrued over the past couple of decades, the enterprise ran into sticky logistical problems from the outset. “Do I understand the forms of their faces better? Absolutely! I could tell you a lot about Ben-Gurion’s forehead. That shaped forehead is fascinating.” It was the trademark hair on the sides of our first prime minister’s head that caused Rain, and subsequently Zaidel, some grief. Zaidel had planned on getting a dozen one-meter-square paintings from the initiative. In the event, he had to allow the painter some leeway with the very first item.

“Ben-Gurion was the one I didn’t do square,” notes Rain. “I told Myron, ‘I can’t do it; this isn’t going to work. I often paint square; but if I did that with Ben-Gurion, you wouldn’t know who he is.’” In the end, the project starter came out a little larger, but Rain managed to stick to the dimension proviso for all the others.

It wasn’t entirely smooth sailing after he got over the Ben-Gurion hurdle – he singled out Ehud Olmert’s visage as being highly challenging – but he successfully completed the full commission as we will all be able to see for ourselves in just over a week from now.

There may be some messages we could do well to take on board from the pointillist works, particularly with regard to the way we view them and how that can inform our standpoint on everyday life. If you stand up close to the works, you won’t make head nor tail of them. You’ll get lost in the minutiae.

To make sense of it all, you need to step back and reflect on the bigger picture. ❖

Entrance to the exhibition is free. Open April 24-May 7; Sunday to Thursday 10 a.m.-4 p.m.