Illustration doesn’t always get its due as a serious art form. Many perhaps consider it as just an aesthetic addendum to the text or possibly as merely an advertising idiom. But here, at least once a year, the Outline Festival elevates the illustrators’ profile with scores of exhibitions across the city, including some al fresco displays.

The seventh edition of the festival is now in progress, under the guidance of founding artistic director Noa Kelner, with numerous exhibitions running at galleries around town through to March.

Since its inception, the festival has deftly wedded the pictorial with the verbal, with the current installment running under the self-explanatory banner of “Illustration and Words in Wartime.” The diverse spread of creations includes works that were originally uploaded to the Internet and gained exposure of varying viral proportions before being adopted by Kelner for Outline.

“This year’s festival mainly collates things from the Internet,” she notes, adding that the armed conflict necessitated a shift in thematic focus.

“We realized we couldn’t do what we had originally planned. We wondered what we should do. Then we saw that even if we did nothing ourselves, the Internet was swamped with images and illustrations and the work of illustrators who were among the first to react” to the terrorist attacks and the war.

“We couldn’t ignore all of that. So we decided to give all that a platform in Outline: Let’s allow these works to be shown live in the real world.”

Having spent all my “formative years” – presumably we continue to “form” throughout our lives – long before the advent of the virtual world, I applaud the transition from screen images to works one can see in the flesh, so to speak, not only in art galleries but also out there on the street. Kelner, a member of a much younger generation, was up for that as well.

Unexpected makeover

Kelner says the illustrations underwent something of an unintended makeover by virtue of the move from the disembodied, intangible realms of the digital universe to the everyday physical public domain.

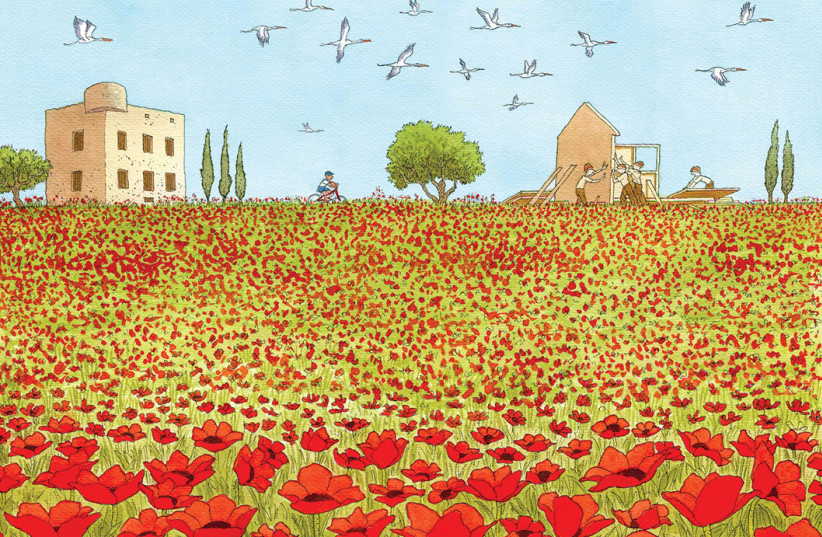

“There is something wonderful about the transformation in many respects. If you take, for example, the illustrations of Yaara Eshet and Sharon Rimmer Boyle.” That refers to the “Metziyut Pruma” (“Threaded Reality”) exhibition at the outdoor Black Box display facility in front of the Clal Building, running until the end of February.

By all accounts, the layout appears to be the complete antithesis of online presentation formats and the source dimensions. “The illustrations are shown really big,” says Kelner. “And these are works which were made really small, and with great delicacy – works of embroidery and watercolors. They are shown in giant size, out there on the street.”

Kelner says her curatorial philosophy was guided by a powerful desire to get things out there, fueled by the tragic events of October 7 and the ensuing warfare and ongoing angst.

“Take, for example, the works by Or Yogev, who suddenly brought things out, and relates to the substance.” Yogev’s “Conflict Line” exhibition closed this week at the old Shaare Zedek building on Jaffa Road. His works exemplify the online-corporeal transition, taking in creations that were fueled by media coverage of the horrific events down south as they unfolded. The images went viral and served as a kind of diary of the violent developments in real time.

There seems to be something intrinsic to the illustration format that facilitates the portrayal of real incidents in an evocative, emotive, and user-friendly manner. Somehow, Yogev managed to impart highly traumatic events in a way that is both artistic and aesthetically pleasing without prompting cause for alarm.

Kelner reprises the digital-corporeal theme and the advantages thereof. “Yogev’s works took on physical form because we used screen printing technology. That, I think, turned the works into something else. You get something completely different with that.” As someone with a tendency toward technophobia, that certainly speaks to my way of viewing the world around me.

THERE IS something fundamentally simple and unpretentious about illustrations. We encounter them from the word go as our parents “read” to us from picture books, as the images leave an enduring pictographic imprint on our tender and still pliant minds, which go on to color our perception of the world – and art – throughout our lives.

Illustrations do just that. They augment and amplify textual material and manage to convey story lines and emotions succinctly across all sorts of cultural, sociological, and narrative domains. It is often a case of less is more in terms of the detail and strata the pictures comprise, although visual complexities are also part and parcel of the artistic pursuit.

“Illustrations can be challenging, but they connect inside us with things that relate to innocence and primordial ways of thinking,” Kelner posits. There is, she feels, a core simplicity to the discipline that draws us in. Interestingly, she notes that the filmic form can offer similarly alluring rewards, particularly when the artist adopts an elementary approach to the finished article.

“The animation we have in the festival is, in fact, pretty basic animation, in loops. You get characters that repeat – they fall down and get up again. You don’t have long multi-stratified story lines.”

Kelner clearly believes in sticking to brass tacks and not overloading the viewer with information. That, by definition, can leave us to do some of the work and complete the picture – literally – in our own mind’s eye, thereby luring us into the thick of the action.

“You can use a single figure, and the viewer will immediately understand what is going on and what they feel about it.” In an increasingly information-laden world, that comes across as a delightfully refreshing line to follow.

Illuminating our world

Kelner spells out her take on the illustrative field and how it helps us to understand the world around us, notwithstanding the linguistic leap of faith that this entails.

“Illustration sheds light, as its name suggests,” she says. To appreciate that illuminative play on words, it helps to know that the word for “illustration” in Hebrew is iyur, and to illuminate translates to leha’eer. In Hebrew, the shared root is glaringly evident.

There is, the artistic director proffers, a core benefit to examining various issues and content through the medium of illustration. “It illustrates some particular aspect of a text [in a storybook], but here I feel it sheds light on reality. It allows us to see a different side to the situation.”

In the current state of affairs, that can bear highly emotive fruits. “I know a lot of people who looked at illustrations and suddenly felt something open up inside them, and wept. They have said that illustrations enabled them to cry for the first time” about October 7. “They said it allowed them to understand, for the first time, their feelings about it all.” That has to be a therapeutic and comfort-providing boon for many.

There has also been some adventuresome fare rolled out in this year’s Outline. The “Anima Verite,” showing at the Wild Gallery, housed in the former President Hotel building, had two animator-directors working on developing a new aesthetic language that is wordless and does not follow any premeditated narrative framework. Intriguingly, “Anima Verite” focused on the interface between memory and imagination as we followed the road to the finished animated article.

October 7: Artistic expression

No local artist today can entirely circumvent the events of October 7 or what transpired in the wake of the massacre. Even if it is not depicted in so many words, the shock waves of the Hamas brutality continue to wash over us and to color the ensuing earnest artistic expressions.

Many of the Outline exhibits convey not only the emotional zeitgeist but also touch on the actual logistics of daily life for many of us these days. That naturally includes the current limbo lot of evacuees from the South and the North, which is addressed in the “Bein Shnei Batim” (“Between Two Homes”) exhibition, which opened this week at the Hutzot Galley at 17 Jaffa Road, across the light rail tracks from the municipality.

Under the curatorial aegis of Naama Lahav, six Jerusalemite illustrators ponder what it means to take up temporary residence. Before getting into the creative stuff, the artists spent time with evacuees from Sderot currently housed in Jerusalem until the authorities deem it safe for them to return to their real home bases.

This was a hands-on, highly personal venture in which the illustrators got some idea of the trauma the evacuees experienced in October, and what it means for them to live in a town that is constantly subject to attack – and to live with seemingly endless tension.

“They talked about what they went through on October 7, and their escape and the move to a hotel and what that is like for them: to be there instead of being in their own homes,” Kelner said. “The illustrators listened as only illustrators can. They know how to listen to people’s stories and translate them” into visually aesthetic form.

It was, Kelner notes, very much a matter of stepping to one side to allow the subject’s story to come through as freely and unfettered as possible. That sounds like a daunting assignment for any artist. After all, art is basically about how the artist views the world about them through their personal, emotional, and/or physical prism. The end result, by definition, is always going to have at least something of the creator in it.

“The idea was for them to tell the subject’s story as fully as possible without getting in the way,” she explains.

The exhibition achieves that with aplomb, with the artists providing some idea not only of what it was like to live in a war zone but also what it means to be uprooted to an albeit relatively comfortable but alien environment far from the intimacy of one’s own four walls.

THERE IS also humor in the exhibits, which span a range of genres, generally of a darker ilk. The picture by Niv Joshua Dreyfus Abudaram, for example, depicts a young man tranquilly reposed in bed with a “Do Not Disturb” sign hanging from the clothes line outside. A tree with flame-like branches, growing in the inner yard, adds an intriguing dimension to the work.

Katya’s Story, by Tamar Lev, paints an oxymoronic blend of “normal” day-to-day Jerusalem life cocooned within a ring of raging flames and approaching rockets. Meanwhile, the titular character gloomily observes both settings. And Noam Nadav manages to squeeze a smile-inducing element into his work as he portrays a clearly religious family running for their lives while exclaiming “Gam zu letova!” (‘It’s all good”).

It wouldn’t make sense to keep the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design out of an illustration-based venture in the capital, and the Visual Communication Department is in the festival mix with gusto. It is a fundamentally positive and celebratory endeavor called “Zikaron Otef” (“Envelope Memory”), which naturally references the Gaza envelope region. Touchingly, the word “otef” also suggests a supportive, embracing element.

The exhibition was initiated by Illustration Section head Amit Trainin and comprises works by teachers, graduates, and fourth-year students and, as such, no doubt accommodates a broad sweep of styles, idioms, and degrees of artistic maturity. All told, the expansive project features 70 illustrative efforts.

As Jerusalem is home to many of the country’s top arts educational institutions, the Outline roster fittingly also features works by students, graduates, and lecturers from Musrara – The Naggar Multidisciplinary School of Art and Society. The “Ma She’kara” (“What Happened”) exhibition, at the Corridor Gallery in Canada House, is curated by Rinat Gilboa and reflects the torment and shock of October 7 but also injects some promising rays of light into the display continuum.

“Ma She’kara” also references the comparison, made by many, between the Hamas attack in the South and the trauma of the Yom Kippur War in 1973.

That is palpably and emotively conveyed by the inclusion of a poem by American-born writer T. Carmi written in 1973 in the aftermath of that war. He takes a brave line on confronting pain and trauma: “What happened – really happened,” he writes. He concludes the solitary stanza with: “I believe wholeheartedly, that I will have the strength to believe, that what happened – really happened.”

The visual offerings of the Outline Festival will hopefully help us to ingest and digest October 7 and post-October 7 so we can move on with belief in a better future. ❖

For more information: outlinejerusalem.com/