Just the mention of the word Holocaust conjures up all sorts of distressing images. Pictures of cattle cars, electrified barbed wire fences, watch towers, emaciated figures, older people on their hands and knees scrubbing the sidewalk while onlookers laugh with pernicious glee, and even more bone-chilling scenes, immediately spring to mind. But, as simplistic as it may sound, there was life, plenty of rich Jewish life, across Europe before Hitler rose to power.

That comes across vividly in the “And I Still See Their Faces” show lined up for the forthcoming Photo Is:rael festival, now in its 11th incarnation, at the Enav Cultural Center and Ofer Garden in Tel Aviv, March 27-April 6. The expansive program takes in a full 50 exhibitions, with works by hundreds of leading photographers from Israel and abroad, and there is a slew of performances, video art, and music and other productions lined up for the 10-day run-out.

The festival roster encompasses a broad sweep of subject matter in addition to the slot that marks the 80th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising which, in fact, took place in 1943, between April 19 and May 16 of that year to be precise. The current edition of Photo Is:rael should have taken place in November but, like all cultural enterprises scheduled for the first month or two following October 7, it was then put on ice.

The show is the result of an emotive and evocative initiative conceived by Jewish Polish singer and actress Golda Tencer – director of the Jewish Theater in Warsaw – and the Shalom Foundation which works to preserve and disseminate Jewish culture and history in Poland.

“And I Still See Their Faces” began life close to 30 years ago when Tencer put out feelers for photos depicting Polish Jewish life before World War II. The public appeal elicited an overwhelming response, with thousands of personal and other photographs submitted. Some had lain dormant in attics and basements following the war, while others were discovered among bombed-out ruins in cities, towns, and villages across the country.

All told, Tencer collated some 9,000 photographs, producing a captivating and distinctive archive that offers an intimate portrayal of the daily lives of ordinary Jewish folk on the brink of a cataclysm. The vast majority of the subjects did not, of course, survive the Holocaust.

Exhibition curated by Michal Shapira

The exhibition, supported by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute and the Shalom Foundation Archive, Poland, is curated by Michal Shapira.

Shapira says she had her work cut out for her when she and Photo Is:rael founder and artistic director Eyal Landasman popped over to Warsaw to get a firsthand impression of the pictorial harvest Tencer had reaped back in the 1990s.

“Golda opened up boxes for us and showed us the digital archives,” she recalls.

Thank heaven for technology. Some of the photos had been lying around in all sorts of atmospheric conditions, and many badly needed some state-of-the-art tender loving care. That was duly administered over time and eventually, there was something to show the world.

“They brought the pictures to a decent level of quality and they began to take them on the road, as an exhibition,” Shapira explains. And now it’s coming over here.

WHAT THE public will see in Tel Aviv are glimpses of quotidian life in all sorts of settings and walks. What could be more commonplace than, for instance, two elderly women and a man perusing the contents of a newspaper, the Berliner Tageblatt, founded by German Jewish publisher and philanthropist Rudolf Mosse, which began life in 1872 and – no surprises here – folded in 1939. Then there’s a fetching shot of eight young gents, in summery class A duds, posing on the running boards and roof of a long vehicle, possibly a bus, with facial expressions ranging from studious to sunny.

The media also pops up in a stolid yet, somehow, appealing portrait of a presumably middle-class couple with the gent holding a Yiddish daily. There are curious images too, such as one of a waist-coasted chap wading through water while half a dozen assorted hats repose upturned on the bank or bob on the ripples. Holiday snaps at ski resorts and at the beach also feature in the show. There is a nary a whiff of impending doom. Therein lies the charm of the collection.

Taking a gander at 100 or so of the snaps put me in mind of the footage captured in Three Minutes in Poland, shot by David Kurtz in August 1938 in the small Polish town where he was born, before relocating Stateside with his parents. The film, subtitled Discovering a Lost World in a 1938 Family Film, was discovered by his grandson, Glenn Kurtz, and provides us with a rare view of a pre-war Jewish community there. For many of us, that was the first time we were able to consider what mundane life was like in a Polish town with a large Jewish population. Less than 100 of the 3,000 Jewish residents survived the Holocaust.

Happily, at the time the film led to a couple of the survivors reuniting and, possibly, their descendants striking up a strong bond. Perhaps something similar will ensue from “And I Still See Their Faces,” as visitors to the exhibition recognize their antecedents in the photos. Stranger things have happened.

Shapira is keen for us to connect, closely, with the vibrant Jewish life that existed, for centuries, in Poland before the Holocaust.

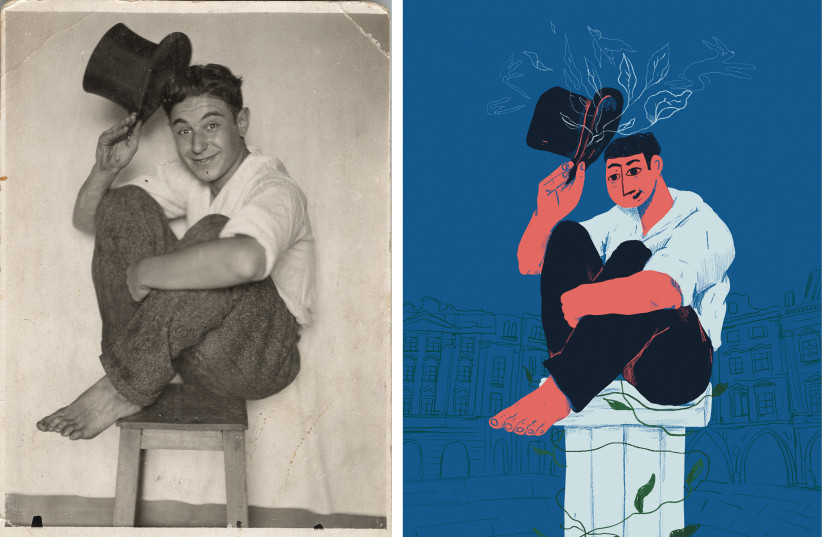

“When I saw the photographs, I told Eyal that it is very impressive and powerful because you see people getting on with their lives. It is also fascinating to see where they photographed – outside or in studios. The latter include delightfully hammed-up portraits made by a photographer in the town of Kozienice, around 120 km. south of Warsaw. Subjects appear holding, or sitting on bicycles or posing woodenly in a fake car.

The exhibition is not just about delving into the pre-Holocaust past. Indeed, there are also photographs in there from the Warsaw Ghetto.

Shapira chose to bring the archival documents into the here-and-now by enlisting a bunch of young artists, from various disciplines, to use some of the old photos as a launching pad for new creations.

“I had the sense that there is something about the way we look at photographs from that time, that we don’t consciously see the details,” she posits.

“We don’t see actual life, we don’t see the intriguing and interesting things because we have masses of these pictures. You don’t manage to discern the details there because we look at the photos in a certain way.”

The accompanying illustrative redux take-show may help in that regard.

“I wanted to give the collection a twist,” Shapira explains. “I wanted young illustrators and other artists – 25-year-olds without a direct connection to the Holocaust.

“That allows a new perspective on the photographs, from a distance of two or three generations. And you have color.” And youthful, fresh, dynamic energy, which should make for a tantalizing oxymoronic viewing experience.

For more information: photoisrael.org/en