More and more of my friends seem to be talking about doing the Daily Daf of the Talmud. What do you ladies know about this? Do you do it?

Rachel

Beit Shemesh

<br>Pam Peled:

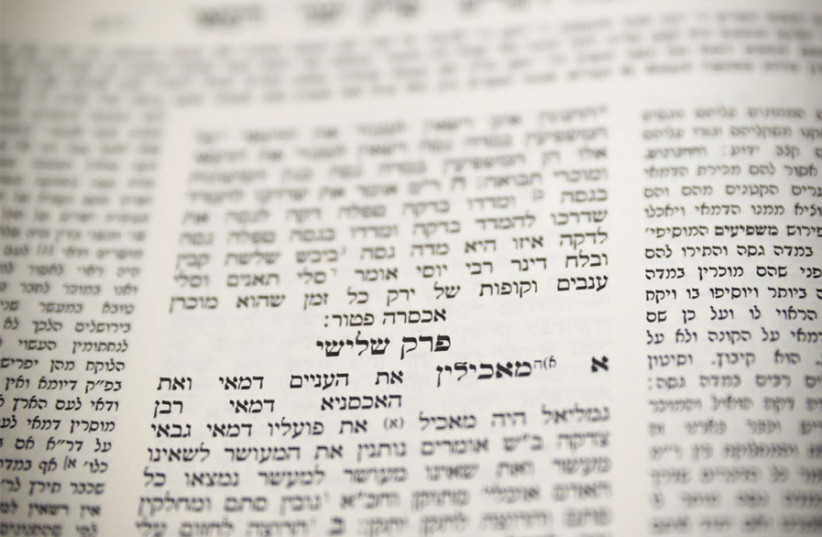

I’ve “daffed” religiously for over two years, admittedly in a very abridged format. My first encounter with the holy texts discussed whether a daughter could reach through an outhouse window to scratch her dad’s head while he was voiding his bowels. Subsequent days dealt with negotiating passing wind, or stepping in animal poop, while praying.

I was astonished. This is the sacred Talmud, the seat of spirituality? Tractate Shabbat was more elevated, but the trigonometry of the allowed angles of baskets of food out of windows, and whether you can walk home after eating (or does this constitute carrying, albeit in your stomach?) was too complicated for me. Yevamot, the present section, considers gender issues: the status of a woman, for example (and her child), if a man falls off a roof landing up inside her, and unintentionally impregnating her.

Of course, there’s context to consider, and tradition, and the gift of debating metaphor and minutia, and how this hones the brain cells. Still, the thought of men studying this for lifetimes, instead of doing the army and working, is seriously insane to me.

What I do get is the community: people “daffing” together from Sydney to Shanghai, sharing podcasts and websites and siyumim with bagels and chocolate chip muffins. There’s a whole industry around the daf: WhatsApp groups that wish you well when you’re not, send food in times of need, send flowers in times of joy. It’s remarkable, and embracing, and sincerely makes life sweeter. I believe that’s the attraction of religion: the belonging, the group, the shared values and way of life. The content could, I suppose, be almost anything.

<br>Tzippi Sha-ked:

Friends Amy, Deena and Miriam “yom the daf.” I don’t, at least not regularly, but I laud women with the stamina and appetite for it.

Pam is perpetually “astonished” whenever she encounters disturbing or titillating aspects of the Talmud, and she regularly contemplates the bahurim (yeshiva boys) pouring their days into these texts.

To those who are triggered by strange Talmudic examples, my daf friends caution keeping the eye on the ball. While examples might be anachronistic, a tad lurid or even offensive, the goal, says Miriam, is extracting the derivative principals involved in the stories. Amy states: Talmudic representations of reality were different and were used to stimulate research and debate. Our job is to understand the moral fiber within those legal norms.

Deena, who has been studying over 40 years, is enormously thrilled women have access to Talmud and can enter into this intellectual sparring ring. While some Talmudic language can sound regressive to “progressive cultural ears,” the underlying principles remain relevant as ever.

“Yes, the Talmudic writers and redactors sometimes couched examples in the absurd, in order to highlight limits, parameters and definitions within Jewish law.”

Deena notes that many laws dealing with Jewish life are sexual. One’s legal status depended a lot on sexual development, and the Talmud is indeed “descriptive.” Western culture, she says, makes a superficial divide between religious and personal life, but from a Jewish point of view, there’s no distinction – every topic is fair game!

Finally, there is value in learning Talmud to understand Judaism’s legal foundation.

<br>Danit Shemesh:

Our ancestors, yours and mine, spoke “Torahspeak” for over 1,000 years, without it being written down on paper, a spoken word. It was a common denominator connecting us as Jews.

Distress and difficulty weakened our people, manifesting in memory loss. The day Moses died they forgot over 3,000 halachot, somewhat like collective dementia.

So, Rabbi Yehuda Hanassi decided to collect the mishnayot, or iterations (memorizings), into one book, in order to preserve us as a nation.

It took another few hundred years to transcribe the Gemara, an exploration of the mishnayot. Gemara is our way of tuning into the machinations of creation; it’s looking under the hood of the world. It includes nature, time, currency, the human psyche, as well as laws and their rationales. It often uses metaphor or absurd situations as a teaching tool.

Shlomo Artzi’s grand-uncle, Rabbi Yehuda Meir Shapira, had the original Daf Yomi idea. The rationale was to make studying the Gemara inclusive and accessible, not to expose it to illiterate ridicule. It breaks down the learning of Mishna, the construct of the Oral Torah.

Pam mentioned a segment (only a part of a whole) which talks of intent. The accident is a warning to have intent, so as not to hurt anyone physically or spiritually. Women’s rights have nothing to do with the story.

I wonder, Pam, if I, a Shakespearean ignoramus, were to walk in to your lesson midway and express an opinion. How would you react?

I don’t “daf,” mostly because I would not do it justice. Learning the blueprints of God’s world presumes much more effort than I can bring. ■

Comments and questions: 3ladies3lattes@gmail.com, www.facebook.com/3ladies3lattes