We are still inured to discrimination against women who want to enter certain better-paying or high-status occupations because men don’t like the competition, but a new study at Cambridge University that looks back at “suspected witches” in the 16th and 17th centuries has discovered a surprising new reason for misogyny.

While both men and women have historically been accused of the malicious use of magic, only around 10% to 30% of suspected witches 400 or 500 years ago were men. This bias towards women is often attributed to antipathy towards females as well as economic hard times. Now, a historian at the university’s Department of History and Philosophy of Science has added another contributing factor to the mix.

Dr. Philippa Carter, a historian of early modern Europe, argues that the types of employment open to women came with a much higher risk of facing allegations of harmful sorcery (maleficium in Latin). She has devoted 30 years to exploring the subject.

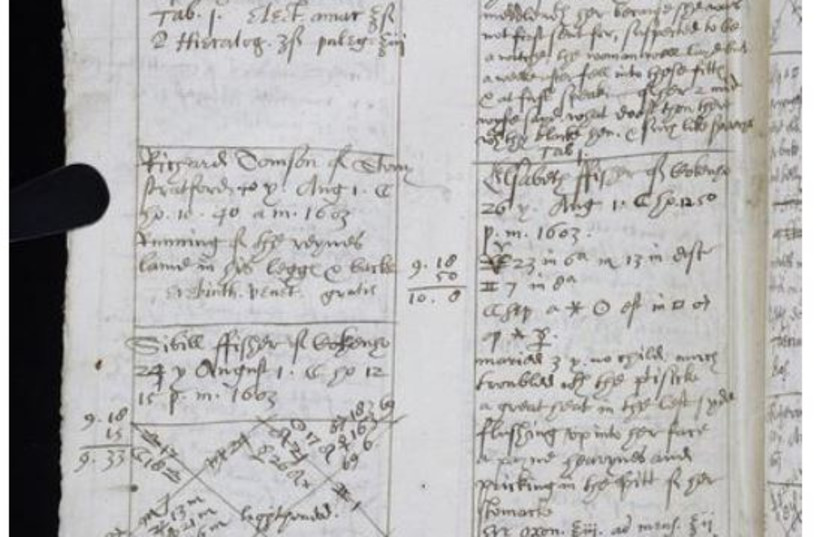

In a study published in the journal Gender & History entitled “Work, gender, and witchcraft in early modern England,” Carter used the casebooks of Richard Napier – an English astrologer who treated clients in Jacobean England using star-charts and elixirs – to analyze links between accusations of witchcraft and the occupations of those under suspicion.

Most of the jobs involved healthcare or childcare, food preparation, dairy production, or livestock care – all of which left women exposed to charges of magical sabotage when death, disease, or spoilage – caused their clients suffering and financial loss.

Women were exposed to greater risk of witchcraft accusations due to gender roles

“Natural processes of decay were viewed as ‘corruption.’ Corrupt blood made wounds rankle and corrupt milk made foul cheese,” Carter said. “Women’s work saw them become the first line of defense against corruption, and this put them at risk of being labeled as witches when their efforts failed,” in contrast to men’s work, which often involved labor with sturdy or rot-resistant materials such as iron, fire, or stone.

“The frequency of social contact in female occupations increased the chance of becoming embroiled in the rifts or misunderstandings that often were the basis for suspicions of witchcraft,” said Carter. “Many accusations stemmed from simply being present around the time of another’s misfortune.”

For the project, over 80,000 of the case notes scribbled down by the notorious astrologer-doctors Richard Napier and Simon Forman were cataloged and digitized.

Napier serviced the physical and mental health needs of people near Buckinghamshire. His records reveal everyday attitudes to magic in the decades before the English Civil War between Royalists and Parliamentarians from 1642 to 1651.

“While complaints ranged from heartbreak to toothache, many came to Napier with concerns of having been bewitched by a neighbor,” Carter noted. “Clients used Napier as a sounding board for these fears, asking him for confirmation from the stars or for amulets to protect them against harm.”

Most studies of English witchcraft are based on judicial records, often pre-trial interrogations, by which point execution was a real possibility. Napier’s records are less engineered; seemingly he kept these notes only for his own reference, she added.

Carter was able to use the now-digitized casebooks to trawl through his notes for suspected bewitchments, which made up only 2.5% of Napier’s total case files. Between 1597 and 1634, Napier recorded 1,714 witchcraft accusations. The majority of both accusers and suspects were women, although the ratio of female suspects was far higher. A total of 802 clients identified the suspected witches by name, and 130 of these contained some detail about the suspect’s work.

Six types of work are featured regularly across the 130 cases – food services, healthcare, childcare, household management, animal husbandry, and dairying. Such forms of labor were either regularly or almost exclusively the domain of women.

Dairy was symbolically tied to women as “milk producers.” Carter found 17 cases of magical dairy spoliation, and 16 involved only women. For example, Alice Gray suspected her neighbors when cheese began to “rise up in bunches like biles [boils] &… heave & wax bitter.” Failures in brewing and baking were also attributed to female witchcraft.

Women often managed food supplies – a power that bred suspicion. Many tales of tit-for-tat maleficium (sorcery) in Napier’s notes derived from spurned requests for food. “Women were both distributors and procurers of food, and failed food exchanges could seed suspicions,” said Carter. One potential witch named Joan Gill gained her reputation after her husband consumed milk she had been saving, and the spoon he supped it with lodged in his mouth overnight.

Not just denying others food but also supplying it could end in accusation. Nine out of ten suspects who sold food were women, with 25 accusations resulting from a bout of sickness after being fed. Many women practiced as local healers (“cunning folk”), but this too was a risky occupation as suspicions arose when treatments failed.

One male customer, troubled with “a great soreness [in] his privy [private] parts”, told Napier a female healer had bewitched him after he sought a second opinion.

Some of the riskiest work was in what we now call “caring professions,” which are still dominated by women today – midwifery, attending to the sick or elderly, child-minding, and so on. For example, 13 suspects had cared for the accuser in her child bed. Infant mortality was high, and the prospect of losing a child often motivated the allegations. Over 13% of all recorded witchcraft accusations naming a suspect involved a victim under the age of 12.

Loss of sheep and cattle was also a common cause of accusation. Just over half of livestock workers at the time were women. This parity can be seen in accusers (28 men and 28 women) but not suspects (15 men and 91 women).

“Napier’s casebooks suggest that disputes between men over livestock could get deflected onto women,” added Carter.

“Gendered divisions of labor contributed to the predominance of female witchcraft suspects,” she said. “In times of crisis, lingering suspicions could erupt as mass denunciations. England’s mid-17th-century witch trials saw hundreds of women executed within the space of three years.

Case 46,520 involved “Mrs. Pedder the Younger, of Potters Perry. 33 years (old). April 30 Thursday 11.30 p.m. 1618. Has not had the right course of her body these three years. Fears a consumption & (asks) what is good to keep her from it. Urine very good. Would have a purge for herself & her husband who fears his father’s disease. (He) cares not for meat (food). Is jealous of his wife (she) being very honest & chaste. & (he) is sometimes lunatic & mad. 4 years & a half, every three or four days. He thinks that he is bewitched with (by) one, a woman that gave his mother physick (medicine).”

“Every Halloween we are reminded that the stereotypical witch is a woman. Historically, the riskiness of ‘women’s work’ may be part of the reason why,” Carter concluded.