If, on the lecture circuit, Jews love asking “why does Israel have such bad PR?” many sympathetic, non-Evangelical Christians often ask: “Isn’t chosenness why there’s antisemitism?”

There’s a simple answer to this question: “no.” Attributing antisemitism to “chosenness,” or to anything else Jews say, believe or do, crosses wires, blaming the victim. Antisemitism – that obsessive hatred of the Jew, Judaism and, now, the Jewish state – reflects on the accuser, not the accused.

Many religions, like many countries, from Saudi Arabia to America, entertain some notion of chosenness. Yet only the Jews’ use of the concept has been used against them so systematically, so consistently, so cruelly.

Of course, the answer is more complicated, too. Chosenness may be the most willfully misunderstood Jewish concept. Ignoring the Torah’s many injunctions to love strangers, and the Bible’s constant universalist affirmations of humanity, Jew-haters – and Jewish chauvinists – misinterpret chosenness to suggest superiority. Politically correct Jews agree, ignorantly exiling from Jewish liturgy the resonant, historic phrase “ata behartanu” (You chose us). Jewish comedians love challenging God: “If we’re going to suffer so – choose someone else!”

More poignantly, the Zionist poet Natan Alterman, reeling from initial reports revealing the Nazi mass murder in November 1942, produced an instant classic, bitterly “praising” God, “who has chosen us mikol ha’amim – from among all the nations.”

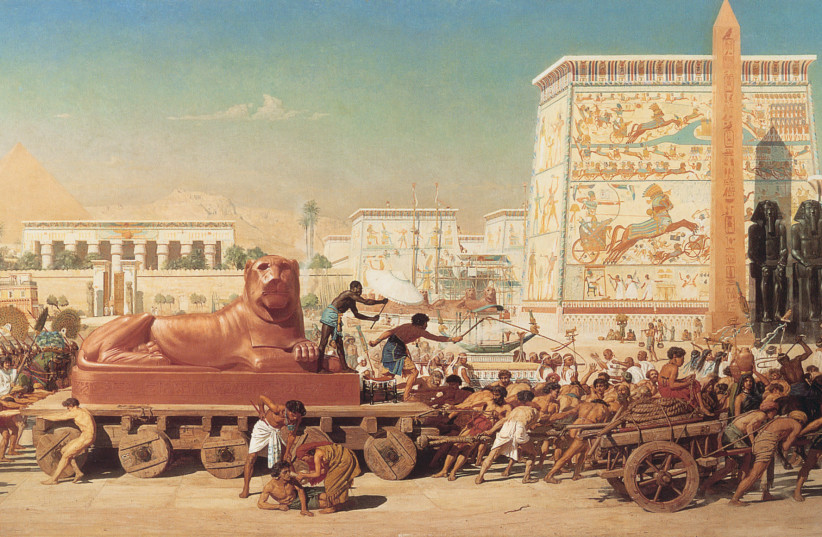

As Jews begin our annual reading of Exodus – in the Torah reading cycle – it’s worth revisiting the idea of the Jews as a chosen people; not to explain how Jews insult others, but to see what Jews can teach others.

In Exodus 19:5-6, the Israelites reach Mount Sinai. God proclaims: “Now if you obey me fully and keep my covenant, then out of all nations you will be my treasured possession – segula mikol ha’amim. Although the whole earth is mine, you will be for me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation.”

In his majestic book Founding God’s Nation: Reading Exodus, the philosopher Leon Kass explains that the Israelites, this “chaotic multitude of abased ex-slaves,” are not chosen “because they are worthy or deserving” but “because they are willing to obey.” God challenges the Israelites to be kind to others – and not lord any presumed special status over anyone else. In going from slavery to a freedom filled with responsibility, the Israelites become the poster children of those free to choose.

And what do they choose? Not riches, not glory, but a mission, striving to become a “treasured people” through kindness and godliness.

Becoming both a priestly kingdom and a holy nation requires forever balancing secular and religious, individual and collective, moral and practical, impulses.

“The call to holiness,” Kass writes, addresses “the people’s need to work through the human penchant for error and evil.”

If Genesis chronicles many ways people sin, Exodus challenges humanity to transcend those urges – showing the exalted way forward. This understanding of chosenness, then, is covenantal and aspirational, not exclusive or superior.

Zionists – especially Socialist Zionists – also interpreted chosenness to stretch Jews, not denigrate non-Jews.

Traditionally minded Zionists, from Rav Avraham Yitzhak Kook to Menachem Begin, were less conflicted and apologetic. Seeing chosenness as essential to the Jewish mission, they celebrated the Jewish character and Jewish rituals as vehicles for advancing good in the world. Left-wing and secular Zionists sweated it conceptually, trying to exorcise any whiff of possible bigotry or what we now call “judginess.”

Golda Meir wrote that the halutzim, the pioneers, “interpreted ‘ata behartanu’ [you have chosen us] to mean that when Jews would return to their homeland, and when they alone would be responsible for their home and society, they would make a better society.” With those dual ambitions, Socialist Zionists needed national fulfillment to do universal good.

David Ben-Gurion interpreted “am segula” as Moses’s call for the Jews to “be a unique nation” by embodying “the higher virtues.” Being “treasured” did not mean being “singled out for special status by God, to be his favored creatures or his superrace.... Rather, am segula implies an extra burden, an added responsibility to perform with a virtue born of conscience.” That’s why, Ben-Gurion admitted, “I have always been very concerned, secularist though I am, with this country’s spiritual state.”

AS WE end this dispiriting secular year of 2021, it’s worth reexamining this challenging nuance, this idealistic juggle.

Today’s far Right pushes group pride to its chauvinist extremes – dividing the world into “us,” the “chosen” ones, and “them,” menacing outsiders.

Simultaneously, the far Left’s obsession about race and victimhood divides the world into those “chosen” to suffer and those deemed to oppress.

Both extremes are nihilistic, clumping people together solely by their group affiliations, not their souls, spreading a European, Hobbesian, dog-eat-dog view of the world. Both kinds of fanatics give identity a bad name.

The Jewish way, now the Zionist way, is more subtle. It embraces identity, but as a collective launching pad toward living well and doing good, stretching everyone individually and communally. Since Sinai, and now in Israel, Jews seek to be tribal enough to feel that strong enveloping sense of solidarity humans crave within their tent, but not so tribal as to hate everyone outside their tent. We seek a community, a nation, committed to raising hopes, not building walls. So, rather than seeing ourselves as “chosen” to judge others, we see ourselves as chosen to challenge one another and help others, making our world and the world truly “treasured,” better for us and for others, too.

The writer is a distinguished scholar of North American history at McGill University, and the author of nine books on American history and three on Zionism. His book Never Alone: Prison, Politics and My People, coauthored with Natan Sharansky, was recently published by PublicAffairs of Hachette.