Chinese officials and policy advisors have often said the Middle East ranks low on their country’s priority list. However, China’s flurry of diplomatic activity with Middle Eastern countries over January, 2022, indicates things may have changed. Against the backdrop of what is increasingly perceived to be American withdrawal, China has gradually been entrenching itself in the Middle East in ways that promise to reshape the region’s social, political and security architecture.

China’s train of Middle Eastern guests started with the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), including its secretary-general and the foreign ministers of four member countries – Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Oman and Bahrain. Then, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavusoglu popped in for talks with his Chinese counterpart Wang Yi. Just two days later, as the GCC representatives were wrapping up their four-day visit, Riyad’s regional rival Iran dispatched Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian to Wuxi, China, to meet Wang.

The GCC countries built on their long-standing strategic partnerships with China by signing more strategic partnerships and advancing free trade area negotiations. Although he did not show up in person, United Arab Emirates (UAE) Foreign Minister Sheikh Abdullah Bin Zayed made sure to speak with Wang over the telephone to discuss areas of cooperation and support between Beijing and Abu Dhabi.

Ankara’s envoy reportedly assured Beijing that it allows no terrorist activities that infringe on China’s sovereignty, which China’s Foreign Ministry website clarified especially the Uyghur Turks. Meanwhile, Teheran’s Minister came to implement the now infamous 25-year cooperation agreement with Beijing – a deal that has gripped the attention of pundits worldwide since its signing in March, 2021.

OVER IN DAMASCUS, China’s support in Syria’s reconstruction seems to have taken a step forward. On January 12, Syria’s Planning and International Cooperation Commission head, Fadi al-Khalil, and China’s ambassador to Syria, Feng Biao, signed a memorandum of understanding on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Just a week earlier, Morocco signed a BRI implementation plan.

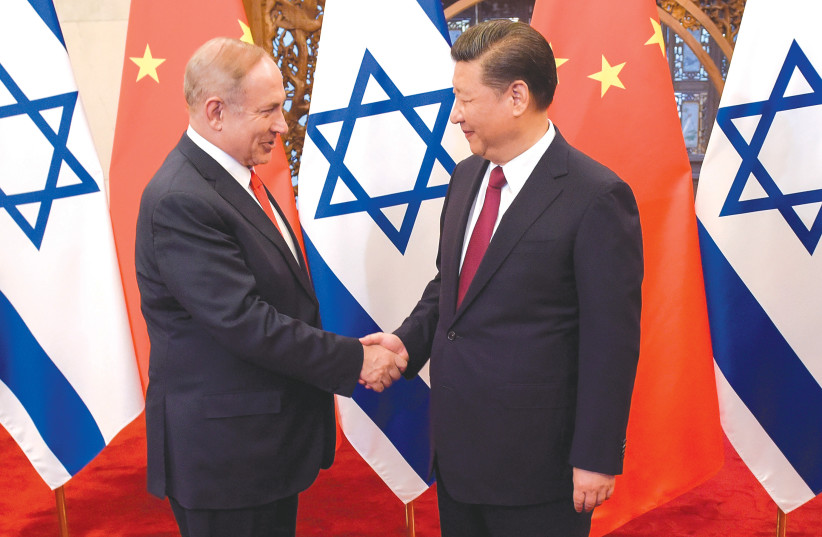

On January 24, President Xi Jinping exchanged congratulatory messages with President Isaac Herzog to celebrate 30 years of official diplomatic ties between the two countries. As well, Premier Li Keqiang and Prime Minister Naftali Bennett jumped on a call to congratulate one another. Meanwhile, Vice President Wang Qishan and Foreign Minister Yair Lapid co-chaired the fifth meeting of the Joint Committee on Innovation Cooperation, signing another three-year action plan to promote innovation collaboration.

In a statement shortly after the burst of diplomatic activity, Wang Yi told the press that the region is suffering from long-existing unrest and conflicts due to foreign interventions. China’s leaders have long considered the United States (US) a destabilizing force in the region, but Beijing has been reluctant to challenge US dominance publicly, mainly because the US’s military presence guaranteed the security of its regional interests. With renewed strategic competition between the two global powers and steps by Washington to leave the region, Beijing’s actions suggest that its strategic calculations have changed.

It is within this broader context that Wang added, “the people of the Middle East are the masters of the Middle East. There is never a power vacuum and there is no need of patriarchy from outside.” We could infer from these comments that China wishes to maintain a low profile when it comes to regional security responsibilities for now, allowing others to shoulder the burden so as to avoid getting sucked into the Middle East quagmire.

As well, Wang’s statement indicates that Beijing wants the region to perceive China as a different kind of superpower.

CHINA’S STATE-LED media promulgates the perception that China wants to differentiate itself from the US as it brands its expanding presence in the Middle East. In a Global Times piece covering the recent burst of diplomatic activity with the region, Zhang Han declared, “China has no enemies, only friends in Middle East.” According to Zhang, the US continuously cultivates the region for its own interests and plants the seeds of democracy, creating chaos and conflicts.”

China is telling Middle Eastern powers that there is another way – a new paradigm for great powers to engage the region.

China’s cautious strategic hedging has indeed seen the country work to maintain friendships with all Middle Eastern countries, establish robust economic cooperation, build political capital and slowly accrue leverage that translates into influence. All the while, China has become dependent on the region for much of the energy needed to fuel its development.

China surpassed the US in oil import volumes from the Middle East over a decade ago. Currently, China sources almost half of its supply from the region, with 375 b. s of crude originating from just six GCC countries in 2020. Despite China’s net-zero carbon commitments, some projections suggest that by 2030 China will be importing 80% of its oil, much of which will come from the Middle East.

However, viewing China-Middle East relations solely through the lens of energy security conceals the bigger picture. Over the past decade, China-Middle East relations have expanded well beyond the energy sector.

CHINA HAS EMERGED as a significant trading partner and source of investment for many Middle Eastern countries. According to the Chinese foreign ministry, China surpassed the European Union as the GCC’s largest trading partner in 2020, with bilateral trade reaching $161.4 b. Meanwhile, the UAE is viewed as a gateway for around 60% of Chinese exports to the Middle East. 2021 saw China overtake the US as Israel’s leading source of imports, with $10.7 b. in goods arriving from the mainland to the Jewish state. Meanwhile, it’s estimated that as much as one-third of the investment flowing into Israel’s vaunted technology sector originates from China.

As many Middle Eastern countries seek to modernize and diversify away from oil, they have looked to partner with Chinese companies to digitize their economies. From Beirut to Baghdad, China is providing everything from ICT infrastructure to finance capital and nuclear energy.

China’s expanding presence in the region has been accompanied by a nascent but growing role in the region’s security affairs. Much of China’s global trade and energy shipments pass through critical maritime choke points that straddle the Middle East and North Africa – regions fraught with conflict and instability. These include the Strait of Hormuz, Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Suez Canal.

Chinese warships have been active in the region since 2008, with China’s naval base in Djibouti, which was recently upgraded to accommodate aircraft carriers supporting their missions. In November, 2021, The Wall Street Journal reported that Beijing was constructing a military facility in the UAE. The UAE presidential adviser Anwar Gargash dismissed US criticism over this development, arguing that these certain facilities in no way could be construed as military facilities. Shortly after, media outlets reported that China had begun assisting Saudi Arabia in advancing its ballistic missile program.

THIS JANUARY, IRAN, China and Russia held their third joint naval drills in the northern Indian Ocean, practicing tactical maneuvers, such as rescuing blazing vessels, saving hijacked ships and shooting aerial targets at night. This exercise comes less than a year after Chinese President Xi Jinping announced that Iran would begin the process of becoming a full member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Cautious not to isolate China’s other friends in the Middle East, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Qatar were also admitted as dialogue partners to the organization, which promotes cooperation on security, crime and drug trafficking.

Preferring the image of an economic power, China seems eager for Russia to become the region’s new security guarantor. As Zhang points out, “Russia has been a notable presence in the Middle East, especially on the Syria issue,” adding that “close coordination between China and Russia can avoid policy contradictions and stabilize the region.”

China’s evolving role in the Middle East hearkens back to America’s first foray into the Middle East in 1928, with the signing of the Red Line Agreement. At that time, oil and economics were driving US regional engagement, while Britain and France dominated the Middle East militarily. Following World War II, things began to change. The French were chased out by Lebanese and Syrian nationalists (with British support) in 1946. However, Britain’s sense of victory was short-lived. US interests in the Middle East expanded, and it gradually became more and more entrenched in the region, eventually competing fiercely with its British ally.

As the British Empire declined, it left space for the US to gradually establish itself as the dominant force in the Middle East. While the character of the international arena today is admittedly vastly different, history certainly seems to resonate with notable impact on the local players, as China reshapes the Middle East regional architecture.

Carice Witte is the founder and executive director at SIGNAL, Sino Israel Global Network & Academic Leadership. Dale Aluf is the director of research and strategy at SIGNAL, Sino Israel Global Network & Academic Leadership.