The Torah world is reeling from the loss of Rabbi Chaim Kanievsky, the prince who presided over a massive, worldwide cross-section of observant Judaism.

His immense stature allowed him to transcend the boundaries that all too often divide the Jewish people; he was the one rabbinic fountainhead that elicited the respect and awe of Jews both Hassidic and non, Sephardic and Ashkenazic, and Lithuanian and North African. The gigantic, overflowing crowd at his funeral – the largest, or certainly one of the largest in Jewish history – provides undeniable, physical proof of his enormous standing in the Jewish world.

Rav Chaim achieved this great renown not because of some political or educational position he held in the haredi world, some celebrated treatise he penned or as the result of an inherited place in a continuing dynasty. He sought neither fame nor power and had no pretensions of popularity or desire to command the lives of others. Rav Chaim was “elected” to his role of scholar and halachic decisor purely by acclamation. Indeed, it was his very shunning of honor – unlike those rabbis who endlessly engage in self-aggrandizement and are continually tooting their own horns – which resulted in his gaining the honor of Jews around the globe.

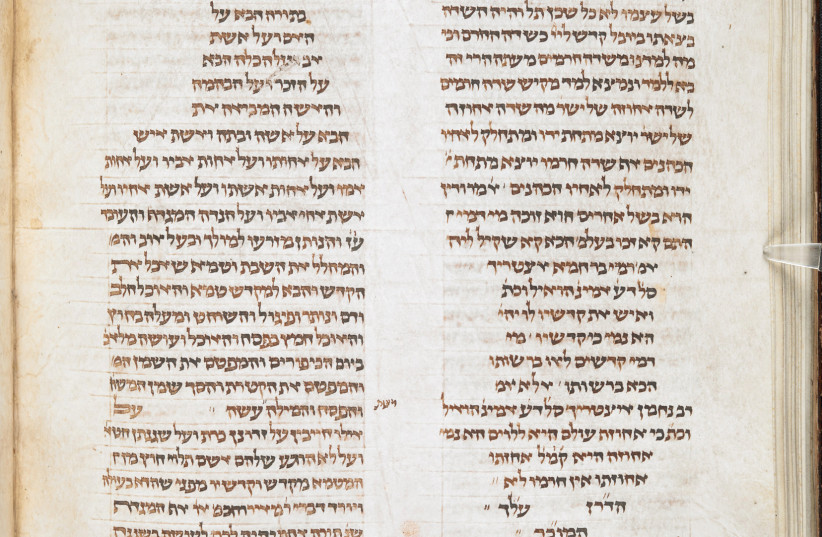

Above all, Rav Chaim was a Talmid Chacham (a student learning to be wise) who never stopped studying, from his earliest years to the day of his death. And his principle course of study, by far, was the Talmud. Sitting in his humble apartment, devoid of the usual creature comforts most people strive for, he would pore over the tractates of the Mishna and Talmud for as many as 17 hours a day, impervious to the vicissitudes of the outside world. Amassing knowledge, what the sages call Torah li’shma (learning purely for the sake of learning), was his uninterrupted pursuit and passion.

While the 24 books of the Tanach are more ancient and perhaps more authoritative, the Talmud has become the discipline of choice for yeshivot around the world. The daf yomi (daily folio of Talmud that completes its cycle every seven years) is studied by hundreds of thousands, becoming ever more popular among females and secular, unaffiliated Jews. It is shared not only in the classroom, but on every outlet of social media, from the telephone to TikTok. In a real sense, the Talmud is the lingua franca, the eternal code-book of Jewish spirituality.

The Talmud is a compendium not just of wisdom, but perhaps even more importantly, the fashioning of the tools one needs to acquire wisdom. The Talmud’s uncompromising search for truth is arrived at by systematically whittling every idea down to its core so that it can be recognized, analyzed and applied. The back-and-forth, give-and-take debates of the great sages (known in Aramaic as shakla v’tarya) hones the ability to discern and discard that which is superfluous and secondary, while grasping that which is primary and pertinent. Many great minds have been shaped by Talmudic study; the industrialist Albert Reichman credited it with developing his acumen for making correct business decisions, while Prof. Alan Dershowitz said it was instrumental in sharpening his understanding and appreciation of the nuances of law. One of the greatest compliments a yeshiva student can be paid is when his rebbe smiles and tells him, “You have a Gemara-kop (a head for learning Talmud).”

When one sits with a chavruta (study partner) and grapples with the text of the Talmud, it is a chore, a challenge and a chance to join the ranks of the greatest Jewish thinkers throughout the centuries. When the Talmud opens, a path toward the Divine spreads out in front of us and we embark on a wonderful journey through God’s garden alongside the heroes of our past. I am privileged to have had and still have great chavrutot who join me in traveling down this holy road on our way to a greater appreciation of Judaism.

SO, IN the memory of Rav Chaim and all the myriad teachers who have inspired so many others, I would like to share some of my favorite Talmudic agadot. These are the anecdotes and moral lessons that accompany the legal discussions in the Talmud, and which help to bring home essential values for life.

Reish Lakish was a highwayman and possibly a gladiator, strikingly handsome and powerfully built. The Talmud in Bava Metzia 84a tells how the sage Rabbi Yochanan saw him swimming in a river and urged him to “use his strength for Torah,” promising to match him up with his sister. Reish Lakish agreed and went on to become a master of the Torah himself. His legendary, fiery debates with his mentor and brother-in-law are powerful and poignant, and are master-classes in the miracle of repentance and the urgent need to respect the greatness in every one of us.

It is not so much the events in our life, but rather the way that we view them. The Talmud in Berachot 60b relates this with the story of Rabbi Akiva who was once travelling with a donkey, a candle and a rooster. He went into a city to find a place to sleep but was turned away. “Everything God does is for the best” he said, and spent the night in a field outside the city. His lamp blew out in the wind, his rooster was mauled by a fox and his donkey was eaten by a lion. Yet, Rabbi Akiva repeated the mantra, “Everything God does is for the best.” When he awoke in the morning, he ventured into the city and saw that bandits had attacked it during the night, capturing many people. Had he found a place to stay, he, too, would have been captured. Had the bandits noticed his lamp in the field, or heard his donkey or rooster, he might also have been harmed. Instead, his life was saved by all the seemingly bad things that happened to him.

A famous Talmud in Taanit 5b teaches us what real blessing is all about: A man was travelling through a desert, hungry, thirsty and tired, when he came upon a tree bearing luscious fruit and affording plenty of shade, underneath which ran a spring of water. He ate of the fruit, drank of the water and rested beneath the shade. When he was about to leave, he turned to the tree and said: “Tree, Oh tree, with what should I bless you? Should I bless you that your fruit be sweet? Your fruit is already sweet! That your shade be plentiful or that a spring of water should run beneath you? You have those already as well. There is just one thing with which I can bless you: ‘May it be God’s will that all the trees planted from your seeds should be just like you.”

The Talmud in Sanhedrin 98a relates that Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi was meditating when he was visited by the prophet Elijah. “When will the Messiah finally come?!” asked Rabbi Yehoshua. “Go and ask him!” said Elijah. “He’s sitting at the gates of Rome, right now.” So, Rabbi Yehoshua went to Rome and met the Messiah. “When will you be coming?” he asked, and the Messiah replied “Today!” Yehoshua went back to Elijah and said that the Messiah had not told him the truth, because he had promised to come today, but he had not come. Elijah explained: “This is what he said to you, ‘Today, if you, Israel, will hearken to God’s voice,” (a reference to Psalms 95:7).

Rav Chaim is gone and for all his praying, Moshiach has not yet come. But perhaps, if we follow his example and devote a bit more of our time to study Torah, then “Today” will actually be today. ■

The writer is director of the Jewish Outreach Center of Ra’anana. jocmtv@netvision.net.il