Back in December, human beings, a weird variety of uniquely frail, lithe and hairless monkeys, launched into space a new, $10 billion dollar telescope, 21 feet in diameter and, like many great temples, covered with golden mirrors.

Peering out into the beginning of everything

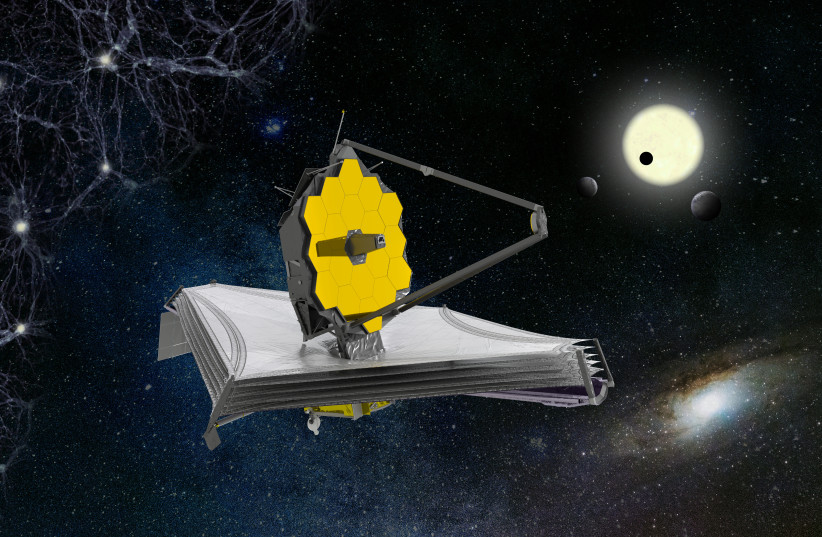

The James Webb Space Telescope is 100 times more powerful than the Hubble telescope. It traveled a million miles from earth with a mission — the first fruits of which we saw last week with the photographs released by NASA — that is almost unfathomably grandiose: to peer out (that is, to look back) at the moment when the first stars turned out and cleared away limitless clouds of primordial gas, seen as light that has been traveling towards us for 13.6 billion years.

Readers of Bereshit — Genesis — learn about a time when all was tohu vavohu — when all was formless and dark — and there is a strong chance that Webb will show us the very moment when something happened and then there was light.

We will be able to see that moment of creation. The moment when the first stars began to burn, unfathomable vessels of brightness that would create the carbon, the nitrogen and the oxygen that make up 86.9% of our bodies, which would later shatter to create our heavier atoms, which would combine with the hydrogen created during the Big Bang. All of this means, by some alchemy of thermodynamics that is, for me, still shrouded in darkness — or perhaps by some act of primordial grace — we are mostly composed of starlight, our mass coming from some mysterious vibration of immortal and timeless energy, echoing through the universe from the beginning of time.

Fires of imagination and ingenuity

This energy has existed from the moment when the very first lights went on and will exist after the very last lights wink out. When all returns to a formless nothingness, those little pieces of starlight that are me will still be there, perhaps joining in a cosmic dance with those that are you, forming something new, maybe something wonderful. These are and were and will be the very same atoms that now make up my bones and blood, and which — through whatever unfathomable, godly magic — fired electricity through my brain, so that one day, also out of darkness, I looked out on the world, saw its lights and colors, discovered the taste and fragrance of milk, came to smile and laugh and walk and speak and eventually (not me but others like me) grow up to build machines to look back in time.

We are the universe coming to know itself.

We are the eyes of God peering out into endless darkness, lighting fires of imagination and ingenuity that allow us to reach into our bodies to make them well, and to travel to the great orbs in the sky, and to look deep into the past, with a golden vessel like the altar of incense overlaid in gold, burning through time and thick with the fragrance of memory, hiding its illuminations somewhere beneath the smoke. And we come to understand what and where and when we are. And we will see the moment that we’ve been reading out for all of Jewish history: “Vayomer elohim yehi or, vayehi or” — God said, “Let there be light and there was light.”

We cannot — and perhaps will never — be able to see further, into those 250 million years after the Big Bang but before the stars, when all was a dark, hot soup, unformed and void, tohu vavohu.

Like you, perhaps, like everyone in the world who has ever looked seriously into the thermodynamics of man, I don’t know what to make of all this. I don’t know what to do with the knowledge that I was forged in starlight or that the space between my atoms is empty, a vacuum, like the void into which, according to the Kabbalists, the Unending poured first light. I don’t know what to make of the fact that every piece of me has existed and will exist for all time.

And yet, it seems as though the fires of my imagination are endless, that my capacities of love and hate, laughter and tears, are endless and abiding and real. And I believe that I am indeed looking out on the world through the eyes of God and, as the great Christian mystic Meister Eckart famously said, that “the eye with which I see God is the same eye with which God sees me.”

I don’t know what to do with the knowledge that all the electrons in my body hum and create this divine illusion of being which is the same as the divine majesty of nonbeing.

But when I imagine myself one day returning to the stars — and when I looked at the new images of the universe released this week by NASA — I am indeed filled with a sense of wonder and humility and comfort and gratitude. Maybe someday we will build a telescope even more mighty. Maybe we’ll go back farther and marvel at the dark work of creation, the world before the letter “bet” in bereshit, the blank whiteness concealing and revealing all mysteries.

Until then, each year, we’ll roll back the scrolls, we’ll read the story again and, with our clumsy and marvelous fingers, we’ll try to touch creation.