Every year in August, the threat of a teachers strike hangs like a pall over Israeli parents, particularly those whose children are too young to stay at home alone. This year is no exception.

It remains to be seen whether an agreement between the teachers unions and the Finance Ministry, with the Education Ministry attempting at mediation, will be reached before September 1. At the moment, a return of world powers to the nuclear deal with Iran seems likelier to materialize in the coming week.

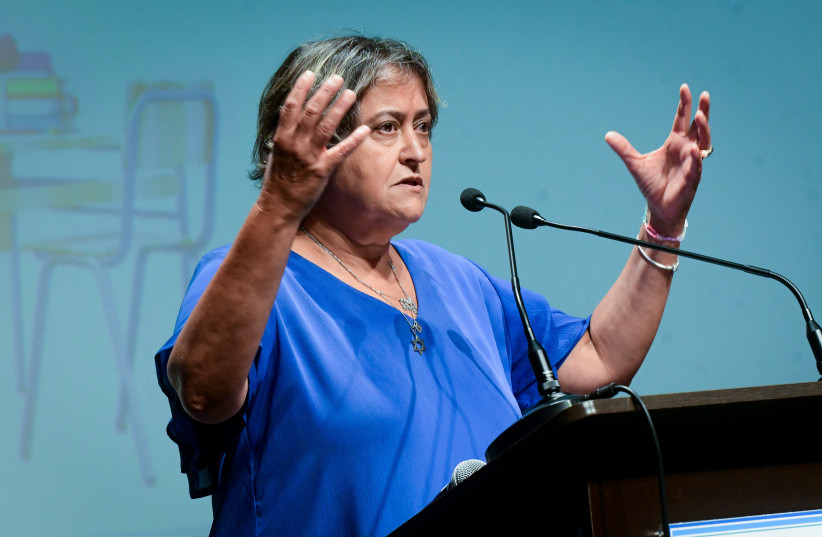

After all, Finance Minister Avigdor Liberman, who proposed a plan that Teachers Union secretary-general Yaffa Ben David and the Secondary School Teachers Association chairman have rejected, isn’t budging from his stance.

His offer, in part, is to considerably raise teachers starting salaries, while providing veterans with a small addition to the amount that they have come to earn by virtue of their seniority. The latter group is not happy, of course. You know, because – in the words of the small humans around whom they spend so much time – it’s not fair.

Like the periodic education-system reforms that have been opposed by the teachers unions since the founding of the state, this one was given a whopping thumbs-down.

The Dovrat Commission

NOTABLE AMONG past efforts at ameliorating the sorry situation was a program created, and implemented briefly in a number of schools with some success, by the 2005 National Task Force for the Advancement of Education, headed by venture capitalist Shlomo Dovrat.

The Dovrat Commission, as it was familiarly called, caused the teachers unions to go ballistic, as it was an attempt to make the education system competitive: to attract and reward excellent educators. This went against every socialist principle on which Israel’s public sector has always operated and continues to uphold, no matter how much it has proved detrimental to the very employees it’s supposed to safeguard.

What the stubborn teachers don’t seem to realize is that when merit plays no role in their advancement, and their pay scale is based solely on longevity, they cannot expect their profession to garner the kind of respect that they rightly claim it warrants. In other words, they can’t have it both ways.

This is not to say that there aren’t wonderful and dedicated teachers who care about their students and consider what they do to be a calling, rather than merely a job. Such educators deserve purple hearts for dealing with crowded classrooms filled with unruly kids – some hard to contain due to their inborn privilege and others difficult to handle for the opposite reason.

The understanding that teaching is as difficult an endeavor as education is important for society causes most pundits to blame the government for failing to come up with a solution. Some also accuse the teachers unions of holding our children hostage right before the start of the school year.

The one aspect of the issue that is rarely discussed is the lack of sympathy on the part of many Israelis for the teachers themselves, who appear not to notice that the rest of us earn just as little for far longer work days and a hell of a lot less vacation.

When confronted with the fact that they are off for two months each summer, as well as for every holiday or semblance of one throughout the year, they protest by saying that they are saddled with oodles of preparatory work outside of school premises.

They reiterate this excuse when reminded of their ability to arrive home in time to serve their own children lunch, while parents without that luxury have to arrange for after-school programs or hire babysitters. Apparently, though, they aren’t aware of the numerous professions that entail lots of (unpaid) work after office hours.

Elementary school

THEY DIDN’T acknowledge this reality decades ago either, during the period that my four kids attended elementary school, and were done and out of the building every day by 1:00 pm at the latest.

Then there was the little matter of those grade-school educators not needing bachelor’s degrees, as teaching certificates sufficed. This may have been a factor in the frequent grammatical errors featured in notes sent out to parents.

Speaking of which, it was I who taught my kids how to read. And it was I who insisted that they memorize the multiplication table.

My having done so went against the wishes of their teachers, who had been instructed by the silly progressives in the Education Ministry that rote was a no-no; children needed to learn how to learn, not recite letters and numbers without absorbing them.

Whatever that means. The teachers sure had no clue.

They were all very well-versed, however, in the practice of enlisting parents to perform various voluntary school tasks, such as painting and decorating the classrooms and chaperoning field trips.

Junior high and high school

JUNIOR HIGH wasn’t much different, though it did have a couple of long days that lasted until – gasp – as late as 2:30.

In high school, the curriculum was more serious, mainly because of the grueling matriculation exams that awaited students in the 11th and 12th grades. But by that time, those without the means to afford private tutors were at a clear disadvantage.

Bemoaning this state of affairs, my son’s 10th-grade math teacher, a young woman from the former Soviet Union, told me she wasn’t surprised that Israeli students were faring so poorly in her subject, considering their lack of basic arithmetic skills. She hastily added that it wasn’t their fault.

“If I had been taught the way they were – or, rather, weren’t – I wouldn’t know math either,” she said, furtively glancing around to make sure that no colleague who might be offended had heard the remark.

Sadly, she wasn’t typical of my kids’ high-school teachers, in general. Still, there were a couple of genuinely good ones who made an impression. The remainder was a cast of mediocre characters, of the variety found in any place of employment.

In this respect, teachers are like everybody else. Indeed, their disgruntlement at thankless work for low pay doesn’t distinguish them from huge swaths of the population.

Nor does their crucial role in our lives set them apart from, say, police officers or nurses whose plight is even tougher, with lengthy shifts at ungodly hours, often on holidays.

The union's unwillingness to negotiate

THEREFORE, IT beggars belief that Liberman’s offer, including a big boost in starting salaries that encourages young people to take up teaching as a profession and overtime pay that incentivizes all educators to work extra hours, is being treated like an affront.

That the main bone of contention – along with a dispute over additional days off – is an insulting raise for the veteran teachers means that they could use a lesson or two in the labor pains of reform. But that would involve their affluent union bosses forfeiting an opportunity to wield power over the entire economy.

The fiasco calls to mind my gut reaction to the last of my kids entering the IDF: utter relief at kissing the education system goodbye for good. Hopefully, for them and their peers with young children, the past won’t turn out to have been the best predictor of the future. So far, the forecast is bleak.