Growing up in suburban Long Island, Friday nights were holy. Not only because of Shabbat, but because it signified the day of rest for my exhausted parents – these two humans who worked day and night to give my brother and me the house, the school district, the Hebrew school, the music, the sports, the dreams they never wanted to deny us. The dreams of middle-class stability they were never given in their own childhoods.

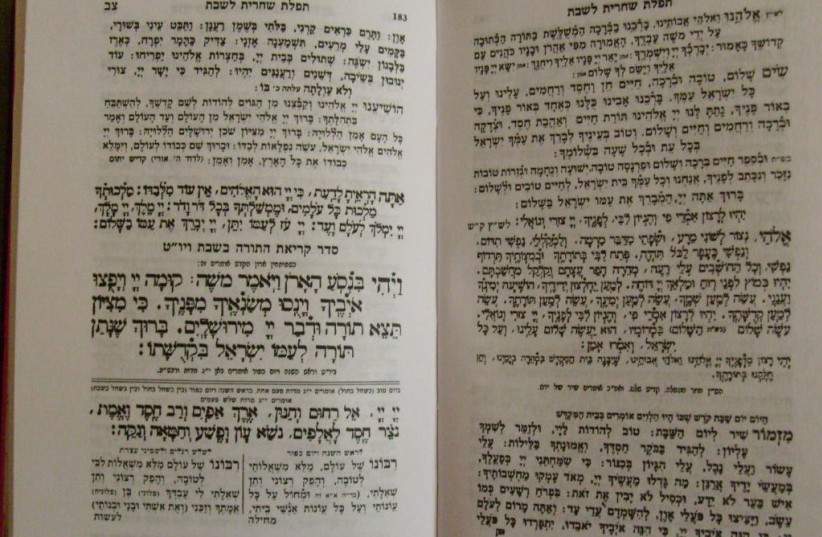

On Friday nights, I watched my weary mother circle her hands three times in front of her, as she blessed the 24 hours of reprieve from work. I watched my father carefully recite kiddish as best he could, having learned Hebrew in his 30s.

My favorite part of this weekly tradition was when hands were placed upon my head, and prayers were given – first to my brother, then to me, then to us both. “May God bless you and keep you. May God shine his light upon you and be gracious unto you. May God turn toward you and grant you peace.”

Hebrew school was a strange and scary place. I was surrounded by girls who looked at my frizzier hair, my darker skin and my fuller lips. They said that I “don’t look like any Jewish girl they’ve seen before.”

I soon learned to hide my history by participating in Shabbat morning minyans, asking for extra credit in holiday group presentations, clinging to the notion that I was just like them. Despite my attempts at fitting in, I saw the other children praised by community members for looking Jewish, for having the right hair and skin tone.

In trying to blend in, I memorized the holidays, the Hebrew alphabet, as if, with this knowledge, I could finally prove that I too, was of the same tribe. I went through books with untold speed, consuming Jewish stories with a hunger that sometimes frightened me. Some part of me craved these plots, conflicts, resolutions, as if, when I looked far enough into these biblical stories of redemption, I could figure out how I too, could be forgiven.

I was always embarrassed when my father drove off in our blue minivan, embarrassed by the other parents’ looks of curiosity mingled with resentment. I was ashamed that no matter how hard I tried to blend in, my father’s presence always ruined this facade.

Long Island Jewish communities continue to be segregated

SHABBAT SERVICES became a weekly reminder of how much Long Island’s communities continued to be segregated, even in its Jewish spaces. My father (besides the synagogue’s custodian), was the only man of color ever seen in our synagogue, and he often was mistaken for “the help” by community members on an ongoing basis.

And like clockwork, as our family walked into the synagogue, I tried, each week, to walk ahead, attempting to place as much physical distance from my secret as possible. But, my father, called me back each time, putting my hand in his, and by doing so, forced me to claim my unique status as my own.

Sometimes members of the synagogue smiled at him, but more often, they acted as if he wasn’t there. They looked away when he casually nodded in their direction. Some of the congregants gave me sympathetic smiles, as if they saw my father as a barrier in my Jewish development, something to overcome and to tell stories about in my old age: “My father was black, but it didn’t stop me from becoming the wonderful Jewish parent I am today.”

I decided to pursue an education in trauma psychology, to understand how the black and Jewish communities both spoke such long and harrowing stories of trauma, but somehow acted as if their stories worked independently from one another. I was most grateful to have a research assistant position at a local Veterans Affairs office on Long Island, in an effort to understand how PTSD is found in the lives of all of those who survive.

Twenty years have passed since I stood at the bimah for my bat mitzvah at North Shore Jewish Center. Twenty years have passed and I still remember the sting of these moments. After being on the Jewish Multiracial Network’s Board briefly in 2019, I excitedly found out that UJA-Federation was funding the first-ever Jews of Color program solely for those “othered” in the Jewish community. In the past 13 months, I found myself participating in the first Jews of Color Initiative Leadership Fellowship, which devoted itself to opening closed doors for people like me.

I see a new generation of Jews of color make their way into the world. I watched them smile, and raise their hands at the Hannah Senesh Jewish Day School in Brooklyn. I watched as they answered questions they felt they had the right to answer. I laughed with children who seemed so resilient to the otherness they symbolized, who are still to this day within Jewish spaces.

To the Jewish people, I say, how long must we wait until we realize love, justice, and the pursuit of truth, is the common language we all speak, and speak together?

The writer is an alumnus of the first cohort of the Jews of Color Initiative NY Hub Leadership Fellowship, an experience funded by UJA-Federation of New York, and has a background in clinical psychology, research, and special education. Tova is an advocate for addressing injustice and discrimination on Long Island through an intersectional lens, and works with various nonprofits, Jewish and otherwise, to attain those goals.